In yesterday’s essay, I provided an overview of my experiences living under the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and outlined the structure of China’s government and its relationship to the CCP. Today, I look at America’s democratic system in order to give a clear picture of what China lacks. I also explore how propaganda and money secure the CCP’s control of the regime.

American Accountability vs. Chinese Authoritarianism

First, regardless of which party is in power in the United States, no party can order the independent judiciary to convict and imprison a person the party doesn’t like or who criticizes the party. This is a regular occurrence in China, as is exemplified by the numerous human rights activists and lawyers—myself included—who have been jailed arbitrarily for their work.

Second, the rights to free speech and freedom of the press are guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution’s First Amendment, upheld by the rule of law, and further reinforced by multiple independent offices and bureaus of the government. At any time, people have the right to expose any wrongdoing of government officials, and cannot be thrown in prison for their speech. Contrast this with my case and the outcome of my exposing the lawlessness and abuses of power by the authorities.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.In America, moreover, the government cannot directly control media organizations, which limits opportunities for the government to spread lies and propaganda. Regular people can and do set up independent media platforms, and as long as there is an audience for such a platform it will expand and grow. Unlike the black box of CCP operations, which no one on the outside can unlock, in the U.S. laws like the Freedom of Information Act ensure that, at the very least, in time the truth will be revealed.

Third, in the United States, the executive branch cannot order Congress—elected by the people—to establish evil laws on its behalf. And the Fourteenth Amendment guarantees that no state can “deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” Constituents in an elected official’s district can easily reach out to their representatives, and can even meet directly face to face with their representative: one need only go through security. No one can prevent regular people from entering the Capitol. Recently, because of the pandemic, there are added guidelines including scheduling times, though I hope these rules will not become the norm.

Fourth, if a president’s election promises are not followed through, the electorate will lose faith and in the next election can choose to vote for a different candidate. Because a candidate needs to win enough votes, different parties do their utmost to explain their ideas about governing the country in order to win the will of the people. After the election, and in order to secure reelection, most elected officials will do what they can to earnestly address and fulfill the promises made in the campaign. Whatever the party, if enough people are unsatisfied, then that official will have to step down.

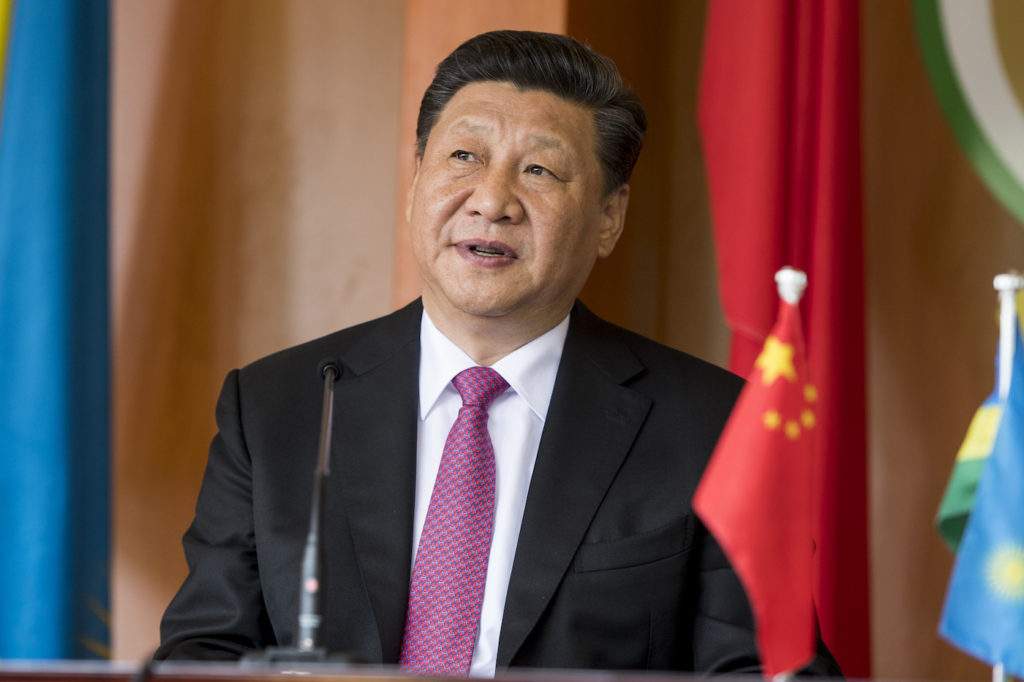

Compare this with the constitution of the PRC, which states that the country “uphold[s] the leadership of the CCP.” In this case, it hardly matters who is in power, because the regime as a whole will never cede power. This has led directly to Xi Jinping’s rise to president for life: in 2018, the hand-raising NPC “voted” nearly unanimously to change the constitution and abolish term limits for the self-anointed Xi.

Under the CCP, it hardly matters who is in power, because the regime as a whole will never cede power. This has led directly to Xi Jinping’s rise to president for life.

Fifth, American governors and state representatives are elected by the people of the state. The president and federal government have no power to appoint or dismiss them. These elected officials follow federal law and the will of the people, but are not beholden to the president. It should be obvious that the chain of responsibility is flipped on its head in the case of President-for-life Xi and the NPC.

This dictatorial system that allows no outside input—on pain of imprisonment or death—has nurtured China’s byzantine petitioning system, that final fruitless avenue for seeking justice, based on the false notion that locals are rotten and those in the center will offer some help. With the police and the judiciary under CCP control and government officials usually punting to the next level up, citizens still hopeful of resolution to a wrongdoing can make the often arduous journeys to the capital to seek help directly from the central government. This is a moment that turns many into activists. Most often, as was my experience, petitioners are told to go back home to seek help from their local officials, creating a maddening, never-ending loop of unresolved wrongs. Sometimes the central authorities call the local authorities to forcefully bring petitioners home. Another frequent response from the center is to detain petitioners—often among the nation’s most vulnerable—or make them disappear all together.

Propaganda and Money

What secures this political structure and its violence is the propaganda machine, wielded by the Publicity Department of the Central Committee of the CCP. Also known as the Central Propaganda Department, its work to control the official narrative extends to all corners of the media and the Internet, from TV hosts to chat groups and the so-called “fifty centers,” those who are paid a small fee for pro-CCP posts.

Sometimes the propaganda is directed at the Chinese people, sometimes at Westerners. The CCP recycles appealing phrases like “getting close with the people,” and “understanding the lives of the people,” which have no basis in reality. President-for-life Xi Jinping claims that when “the people call out, I listen,” which is an outright lie unless it is understood that the implied feedback loop includes censors deleting posts and shutting down accounts online. If you “call out” softly and politely, the CCP ignores you. If you “call out” loudly and insistently, you will be accused of “creating rumors” or “picking quarrels and provoking trouble,” which would likely lead to the public security at your door to arrest you and convict you on the basis of your words. At that point you would likely find yourself stuck in a political black hole.

President-for-life Xi Jinping has tried to attack American democracy head-on for the benefit of Chinese audiences, claiming that between presidential elections, Americans “go into hibernation” with no way of exercising their right to speak. In other instances, Xi has said that, “whether or not a nation is democratic or not should be judged by its people, not by a small number of people who criticize from abroad.” It is of course Xi himself who is making criticisms from abroad, using fake democracy to judge true democracy, and using the so-called “People’s Representative Rule” of the NPC to leave the Chinese people out in the cold for the past 70 years of the CCP’s rule, with no chance to improve the political path of their country as they see fit.

Recently the regime has been taking this concept to a new level by trying to rewrite the definition of democracy, as though by calling a dictatorship a democracy they might actually change people’s minds about the meaning of things like free elections. However brazen and outrageous, this is extremely dangerous, in part because of the motivation behind the lies. This December, the CCP engaged in what it has termed “elections” in the formerly free territory of Hong Kong, and has been crowing about its quest for “universal suffrage” in the territory to “prove”—without a grain of truth—that the regime can uphold its promise of “one country two systems” with regard to Hong Kong. In fact, the CCP can’t even say with a straight face that democracy is bad, so their only recourse is to create a fake democracy, the ultimate in political farce.

In addition to violence, its political structure, and propaganda, there is a final essential ingredient of the regime’s power: money. Money is the grease in the machine of the CCP’s influence campaigns both at home and abroad. In every instance where a foreign corporation or institution apologizes to the regime (including the NBA, Marriott, and the International Olympic Committee, among many others) for critical references to Taiwan or Xinjiang, or for calling out the regime’s human rights abuses, the CCP is buying people off. It persuades them to look the other way when conscience would tell them to do otherwise.

Recently the regime has been trying to rewrite the definition of democracy, as though by calling a dictatorship a democracy they might actually change people’s minds about the meaning of things like free elections.

Contrast and Clarity

When one is caught up in this vast structure, it doesn’t matter that a well-meaning judge or police officer is presiding. All must heed the orders of Party officials, who often sit in the courts as trials are underway to steer the outcomes, as was the case in the “trial” that led to my four-year sentence. Indeed, in the course of my seven-year ordeal, I met more than a few guards who expressed sympathy for me privately. Some said they had no choice but to continue their work because jobs were scarce and they had to feed their families. However, anyone who was publicly sympathetic to me—even with the smallest gesture or word of kindness—would be quickly dismissed.

If I had expressed the views written in these pages while living in China, I would likely be in prison, or worse. This reality sits with me on a daily basis. Yes, the U.S. can do more to ensure that America continues in its pursuit of justice for all. But the CCP’s comparison of democracy with its own brutal authoritarianism is nothing short of preposterous.

Some months ago I had the occasion to seek out my U.S. congressional representatives for assistance. I was more than excited to try out democracy from this level, truly from the ground up, with no frills or fanfare. Would they respond, and if so in what way? Within hours of reaching out, my queries were answered and within days my issue was resolved, all with courtesy and sincerity of purpose. In my mind, I recalled my numberless encounters with Chinese officialdom: threats in response to my reasonable requests; confiscation of property and money; imprisonment for years at a time; psychological and physical abuse. The stark differences between the two realities—Chinese authoritarianism and American democracy—are irrefutable.

Life under this authoritarian regime which has stripped the Chinese nation of justice, the rule of law and human rights, is the closest to hell that there is on earth.

Sometimes it is helpful to see oneself from the outside. When I had escaped my village and was in Beijing with my friends, the only foreign mission we considered reaching out to was the American embassy. We believed the United States to be the most committed to freedom and justice, and also the most capable of standing behind its values.

Since coming to the United States, I see the complexity of the American system with a deeper understanding. As a human endeavor, American democracy is an inherently imperfect enterprise. But there is no question in my mind. If living in a democracy isn’t exactly heaven, it could be said that it’s at least the most humane and just system humanity has yet come up with. On the other hand, life under the authoritarian regime which has stripped the Chinese nation of justice, the rule of law, and human rights, is the closest to hell that there is on earth.

The CCP has destroyed what is good and true about Chinese culture and the Chinese people. My greatest hope for China and the Chinese people—and the world—is for China to quickly find a path to a true and fruitful democracy.

In January, Chen Guangcheng and Catholic University’s Center for Human Rights released its 2022 New Year’s Declaration on China’s Human Rights Crisis. You can read it here.