In her recent book Hostages No More, former Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos provides a detailed portrait of our nation’s education system. In her account, American schooling is marked by lack of educational access, collapsing standards, and ideologically driven curricula. She argues that many of our social challenges can be traced to dysfunctions in early childhood education through graduate and professional schools.

The problems with our educational system that DeVos outlines present a daunting challenge. While attempts to replicate the blueprints of past reform movements are often anachronistic, they can also just as often help us identify blind spots. So perhaps we might glean some wisdom from an almost forgotten social reformer, “The Poor Man’s Earl,” Anthony Ashley-Cooper, the 7th Earl of Shaftesbury (1801–1885), who lamented that the rise of the secular, bureaucratized educational system of his era provided “everything for the flesh, and nothing for the soul; everything for time, and nothing for eternity.” Indeed, Lord Shaftesbury’s success in transforming education for the poor provides a variety of lessons for us today. His “ragged schools” suggest that by increasing local control of schools, expanding vocational training, and introducing curricula that recognize the integrated nature of human beings, our society might become more enriched—both materially and spiritually.

Lord Shaftesbury’s Life

Lord Shaftesbury, whose life and good works are remembered on October 1 in the Anglican Communion, is often overshadowed by the prominence of his near contemporary, the social reformer William Wilberforce. But in Shaftesbury’s lifetime, he was more well-known and beloved—his funeral in 1885 brought larger and more diverse crowds of mourners into the streets of London than even Prince Albert’s several years earlier.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.The world that we now know is a different one due to Lord Shaftesbury’s tireless work on behalf of the marginalized and the oppressed. The scope of his interests was remarkably broad: he helped reform lunacy laws and abolish hard and dangerous labor for children, he laid the groundwork for the Balfour Declaration, and he led movements to provide for poor widows.

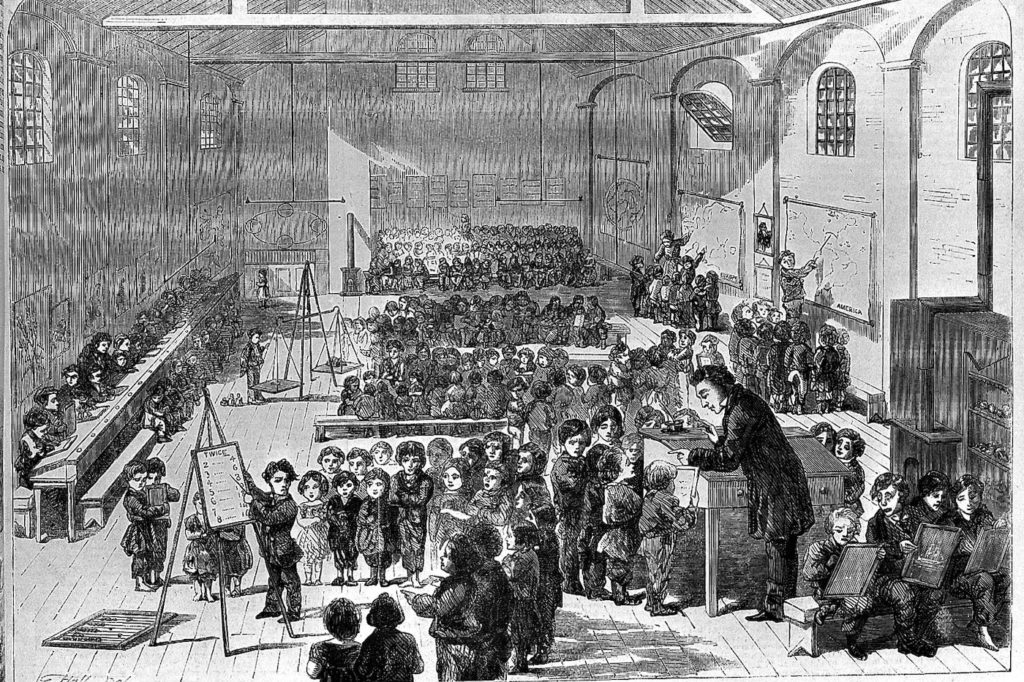

The work of which Lord Shaftesbury was most proud, however, was what he did as the leader of the Ragged School Union. Britain’s ragged schools were intended for the most destitute children, who were often homeless or orphaned. These schools combined traditional academic instruction, moral and religious lessons, and training in a trade. They also provided an escape route out of the destitution that inspired the most disturbing and heart-wrenching scenes of Dickens’s novels. Thanks to the schools, students left this indigent world behind for a life of industry and self-sufficiency. Though quite modest and almost always under-resourced, the schools’ unique pedagogical program, which combined formal, industrial, and moral education, provided tens of thousands of children a pathway into a trade, personal and economic stability, and the emerging middle class.

These schools combined traditional academic instruction, moral and religious lessons, and training in a trade. They also provided an escape route out of the destitution that inspired the most disturbing and heart-wrenching scenes of Dickens’s novels.

The Whole Person

The Ragged School Union was explicitly Christian and articulated its mission in unmistakably Christian terms. It was founded in April 1844, when British culture, then almost entirely Christian, obviously departed significantly from our more secular attitudes about schooling in the United States and United Kingdom today. In addition to their religious instruction, the ragged school students learned math, science, and the humanities. And, most notably of all, the schools employed tradesmen to teach children to become tailors, cobblers, and smiths. The unity of the body and the soul was presupposed by ragged schools’ mission and in their curriculum. No dimension of the human person was ignored in the work of these remarkable institutions. In fact, much of the ragged school literature and records seamlessly move from physical to spiritual to moral language, suggesting these planes of existence are inextricably intertwined.

But in order for students to effectively learn trades, they needed instruction from skilled workers. This is precisely what happened: many of the ragged schools began with more informal educational arrangements, in which skilled tradesmen took on destitute children as apprentices, and then gradually began to offer comprehensive instruction. As the movement became more formalized, schools emerged and met in whatever spaces organizers could find. Instructors in all disciplines, not just the tradesmen, were almost always working people from the area who volunteered their time. Working people made up a significant portion of the schools’ faculty.

The ragged schools formed citizens who could be motivated not merely by economic gain and escaping material poverty, but also by the calling to contribute more holistically and comprehensively to a flourishing society.

The founders of the ragged schools understood that the poor are not poor just because they lack material wealth—poverty is much more complex. The poor are poor because they lack access to opportunity, which comes in the context of mutuality and interdependence. A fully trained young cobbler or tailor would have the skills needed to earn money, to provide for a family, to invest, and, eventually, to use philanthropically. The intellectual, moral, and professional mentorship given to a destitute child did not merely feed a mouth—it created a productive and flourishing citizen, both of the city of man and of the city of God.

By respecting these poor students as moral agents—with dignity, responsibility, and gifts to share with the world—the ragged schools formed citizens who could be motivated not merely by economic gain and escaping material poverty, but also by the calling to contribute more holistically and comprehensively to a flourishing society. The spiritual formation of the students was just as important as providing them with technical knowledge, and the former reality grounded the latter.

How Ragged Schools Succeeded

By the time the ragged schools emerged, society’s conscience had awoken to the miseries of extreme poverty. How to address the plight of the destitute became a matter of serious policy debate. The Ragged School Union was formed when London’s population was less than 2 million; at its peak it consisted of 350 schools, 1,600 educators, and 26,000 pupils. Thanks to the ragged schools, reformers could do more than establish soup kitchens and shelters. Having been educated and qualified, the once ragged child had no need of soup kitchens, shelters, or charity, but could engage in industry.

Ragged schools were as varied as the neighborhoods in which they were situated. The model was adaptable to local contexts. Some schools trained tailors, and others trained cobblers, while still others trained blacksmiths. Some met every day, others in evenings, and still others just on Sundays.

Perhaps the most appealing feature of the ragged schools was that they were scalable. They relied on the community’s resources. The Ragged School Union did not import the best teachers from elite academies across Britain. Rather, they relied on the local knowledge, expertise, and connections that were present in the community already. Ragged schools were as varied as the neighborhoods in which they were situated; the model was adaptable to local contexts. Some schools trained tailors, and others trained cobblers, while still others trained blacksmiths. Some met every day, others in evenings, and still others just on Sundays. Local context shaped the delivery and identity of each school even if all ragged schools in the Ragged School Union were guided by the same fundamental and universal commitments.

This means that modern-day schools modeled on this formula will look different in different places. They must be adaptable to the varied resources, needs, and opportunities that are present in diverse areas. The more centralized and remote the decision-makers are, the less responsive they will be to local challenges and opportunities. Remember, Lord Shaftesbury as the chairman of the Ragged School Union saw firsthand the diversity of the schools and local contexts in which each operated.

Lessons for Today

So what can we learn from the success of the ragged schools? Do schools need to be religious to succeed? Certainly, there is a uniquely Christian approach to understanding the human person that fueled the ragged schools’ pedagogy. And today, we must make room for educational options that are deeply informed by religious commitments. Even the non-religious can surely appreciate the success of the ragged schools movement, and the transformative effects of having a curriculum that acknowledges the unity of body and soul. Of course, an exact replica of the ragged school model championed by Shaftesbury would be difficult to scale in a pluralistic, secular, and economically complex society. But having voucher programs that don’t discriminate against religious schools, for example, would at least mean secular schools with more utilitarian curricula would not be unfairly preferred. The rewards for doing so would be significant for individuals as well as society.

Nonetheless, a Christian approach is not strictly necessary to recognize that children are more than their constituent parts. Schools, religious or not, should teach students that they are more than individuals entitled to demand things from others—they are also members of larger communities that have a rightful claim on their time, efforts, and resources. And in addition to theoretical knowledge, at least some schools should teach students to apply their knowledge industriously.

America’s federal system makes it very possible for the United States to imitate the decentralized, locally controlled approach to education that helped the ragged schools succeed. In fact, many states and local districts are beginning to diversify their school models. Texas, for example, began introducing career-related courses into its curriculum in 2013, and allowed industry employers to help with teaching and developing curricula to teach students skills and trades. And by embracing a diversity of schooling options like charter schools, magnet schools, STEM-based institutions, and schools that focus on vocational training, states can move away from the singular focus on college that so often stifles schools’ missions. Schools would be free to rethink their missions and consider their students’ needs and talents as whole persons—workers, thinkers, community members, and children of God.

America’s federal system makes it very possible for the United States to imitate the decentralized, locally controlled approach to education that helped the ragged schools succeed. In fact, many states and local districts are beginning to diversify their school models.

As in the 1800s, the crises we face today are dire. Lord Shaftesbury’s approach to the ragged schools was not perfect. Much of his rhetoric was colored with a certain paternalism and naïve optimism. But the movement was undeniably successful. The effectiveness of the model was so apparent that Parliament passed the Education Act of 1870 that created free, government-funded schools. Unfortunately, these schools were a secularized and bureaucratized shadow of the ragged schools. Ironically, this dealt a lethal blow to the ragged school movement and paved the way for a system that is marked by the same dysfunctions that Secretary DeVos has described in her recent book.

Hopefully, by looking back to Lord Shaftesbury’s ragged schools, we can learn fresh ways to construct effective, sustainable, and scalable solutions to the dysfunctions that now plague our present system.