A few months ago, I wrote in this space about how my retirement compelled me to cull hundreds of books from my consolidated home and office libraries. After I disposed of almost ten percent of the whole, our house still holds nearly 4,000 books, and while it has room for more, it’s fair to say not a great many more.

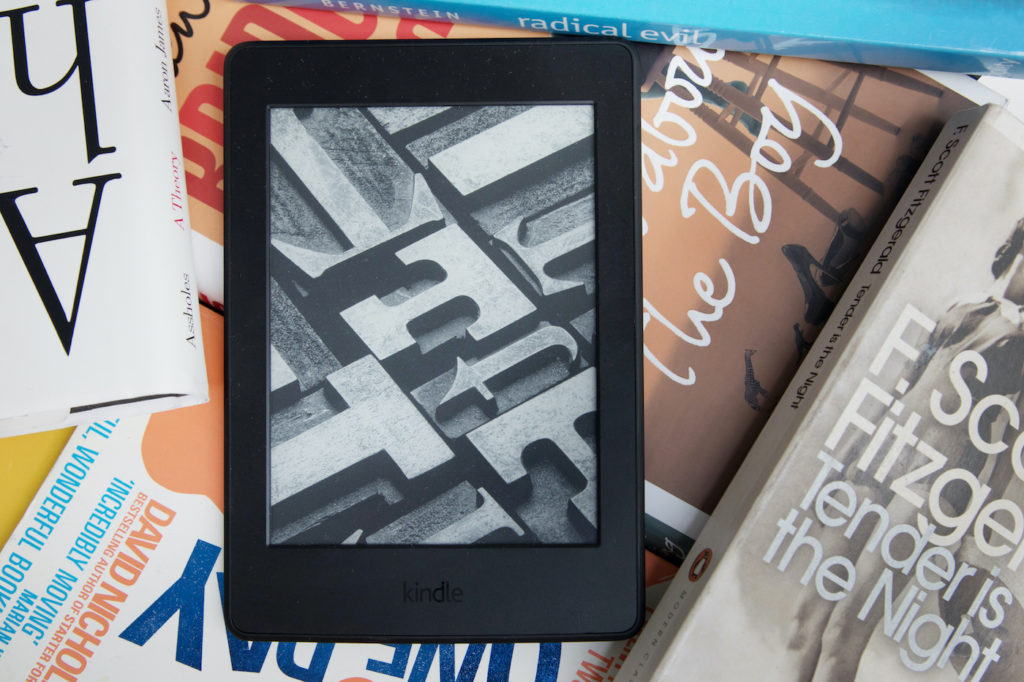

And so my mind turns to the idea of the e-book—all the content of a book in digital form, a data package taking up essentially no physical space apart from the minuscule sectors of a storage drive somewhere, whether on one’s desk, in one’s hands, or in “the cloud.” Ever since the advent of the e-book—before today’s typical undergraduates were even born—some people have predicted the coming demise of the printed book, since the electronic form has so many convenient features. First, of course, there is no shelf space occupied by e-books. With a dedicated e-reader device like Amazon’s Kindle, or a multi-purpose tablet like an iPad, or even with one’s smartphone, one can carry around a library of hundreds of books. Usually—but, surprisingly, not always—e-books are cheaper than printed volumes, since production costs are close to zero after editing and formatting are completed. In typical formats available today, they can be bookmarked, highlighted, annotated more or less like a print book—and then wiped clean again if the clutter annoys us. And e-books cannot be destroyed by fire or water, or be chewed on by puppies, or suffer the ravages of decay from age and use.

Pew Research reported at the beginning of this year that in 2021, 9 percent of Americans read one or more e-books and no print books, 32 percent read one or more print books and no e-books, and 33 percent read books in both forms. (Alas, 23 percent of Americans said they had read no books at all in the previous twelve months.) Thus, bearing in mind the overlap, 42 percent read e-books and 65 percent read print books. I am among the 33 percent who read books in both forms in 2021. In last month’s column, I mentioned having finished a biography of Darwin and having begun another of Freud; what I did not mention is that both were e-books, not physical ones.

In addition to the new books being published electronically, and the publishers’ backlists being reproduced in that form, there is a great wealth of free content available online by way of books long out of print and out of copyright. One might find some of these books in print by searching used booksellers, but there’s no denying the convenience and value, for pleasure reading or research, of the free e-books offered by Google Books, the Internet Archive, and Project Gutenberg, among others. As I mentioned in another column in 2020, one can even turn to e-book formats of books one has in physical form, if the object is to save wear and tear on antique bindings.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.But will e-books make physical books obsolete? Should they? Can they? I think the answer to each of these questions is clearly no. For all their convenience, e-books just can’t do for us what physical books do. I will not dwell on the fact that books, well printed and bound, are appealing physical objects, delighting the eye, the hands, and even (for anyone with antiquarian interests) the nose. That’s true, but a secondary consideration next to any book’s content, which is why I’d rather have a cheap used paperback of a beloved classic than a signed first edition of some schlock I wouldn’t read.

So if the content of any book can be reproduced in digital form, why shouldn’t e-books replace print? Speaking for myself—but others I’ve discussed it with say the same—the experience of reading on a screen does not result in the same retention in memory of what I’ve read. Once, when I was in too great a hurry to order a book in print or even check it out from the library, I bought a Kindle version of a modern classic in political theory. I found what I needed in it for immediate purposes for something I was writing, but now years later I have practically no recall of anything I read in that book. I have a handful of other scholarly works in typical electronic formats, and I have the same experience with all of them: I have a very poor memory of what they have to say.

Speaking for myself—but others I’ve discussed it with say the same—the experience of reading on a screen does not result in the same retention in memory of what I’ve read.

It’s hard to say exactly why this is so. I do know that with print books that have made an impression on me, I can sometimes recall that somewhere about a third of the way in, there is a particularly striking passage on the upper half of the righthand page, and I can find it in moments by turning the pages. Something about the physical act of reading a book—the intertwined visual and tactile experience—stamps these things on our memory. An ebook is just too ephemeral—too disembodied, literally. My conclusion is that for light reading—minor fiction, popular history or nonfiction—an e-book can be an acceptable alternative, since retention in deep memory is not all that important. But in the case of any work that we wish to study and recall—as scholar, as teacher or student, even as simply a lover of literature—our power to retain what we read somehow depends heavily on our physical experience, with hands as well as eyes, of turning the leaves of a book. Hence, as a teacher I have always counseled students not to purchase their texts for my classes in e-book form.

I referred above to “typical electronic formats,” and so I should enter a partial qualification of what I’ve observed. By typical formats I mean those like “.mobi,” “azw3,” “.epub,” and other formats readable with devices and applications like Amazon’s Kindle, Barnes & Noble’s Nook, Apple Books, and so forth. The most convenient feature of these apps and formats is also their defect. They permit readers to adapt the content on the page to fit in the most readable form on their devices—varying the font size, switching from portrait-view of a single page to landscape-view of two pages, and so on. The consequence of such adaptation is that one loses all sense of how many physical pages the book runs, and what actual “page” of the print book one is reading at any moment. On the screen are what appear to be pages of a book, but it is as though we had regressed from the codex to the scroll—from discrete physical leaves printed on two sides, to an undifferentiated stream of text. “Where was it the author said such and such?” becomes almost impossible to fix in memory upon reading, or to relocate later unless one has electronically marked it.

There is a family of formats that bring the e-book closer to the print experience. Google Books scanned from library holdings of books out of copyright, and Acrobat “.pdf” versions of print books, bring to the screen exact visual replicas of the pages of physical books. With an intact reproduction of type on a page, fairly neatly fitting the size of an iPad tablet’s screen, these formats give us at least the visual aspect of physical book reading.

In my research in constitutional law, for instance, I find that reading and annotating PDFs of Supreme Court decisions on my iPad or computer works about as well as printing them to read on paper. This is equally true of new “slip opinions” posted to the Court’s website and of 200-year-old published reports of John Marshall’s decisions. But it has to be images of print for me—Wheaton’s Report of 1819, not a Westlaw-reformatted copy of the text of McCulloch v. Maryland—or my retention problems will resurface. Hence it’s a great blessing that another legal-research website to which many university libraries subscribe, HeinOnline, makes page scans of old court reports and other historic texts and law journals accessible, with PDF downloads available.

Speaking of permanence, there is a final reason why e-books will probably never supplant printed and bound books. That is that e-books are radically dependent on hardware and software that rapidly become obsolete.

It may be that my experience of finding page-scan legal materials satisfactory is partly owing to the fact that I have spent so many years reading such things that I can move through them fairly quickly, staying alert for the meat of the argument (invariably a small proportion of both judicial opinions and law review articles). If every page—every paragraph—“counted,” I think I should want to have a printed copy in my hands. A page-scan copy from Google Books might suffice in a pinch, but for anything dense in meaning that is of permanent importance to me, I want a physical book if I can get it.

Speaking of permanence, there is a final reason why e-books will probably never supplant printed and bound books. That is that e-books are radically dependent on hardware and software that rapidly become obsolete. To give one personal example: I have one hard copy of my own doctoral dissertation, produced in a word processing format that is so outmoded I cannot open readable copies of those old files on the computer I have today. One day the devices and applications that make today’s e-books appear before our eyes will be obsolete. Will all the e-books in existence today survive in digital form a couple centuries from now?

For all the decay from age and use that I mentioned above, physical books have a remarkable durability. The oldest book in my library was printed and bound in 1739. The “hardware” is rag paper, ink, flaxen thread, cloth, and leather. The “software” is the English language. No advances in technology have made this particular copy of this particular book inaccessible to readers in 2022, and it will remain accessible as long as it is not destroyed and people still read English. I don’t know that I can say with confidence that any e-book I now have will be readable in the year 2305. Long live print!