Recently a Twitter acquaintance (and isn’t it some world we live in, when we know people only in such virtual places?) remarked, “There are too many books. What are your strategies for which books to read and which not? And how do you fit personal and recreational reading in around professional reading?” Another Twitter acquaintance quote-tweeted the first and directed the query to me—and here we are.

The last question, a natural one for an academic whose work is largely to read, is the easiest to answer. Work cannot consume our days. One just has to make time, and make a habit of reading for pleasure. Whether it’s the evening, or bedtime, or early morning, or weekends, make regular time for reading that has nothing to do with work. I can think of nothing more pitiful than a legal scholar sitting up in bed with law books, or a literature professor with literary criticism. Many of us read books in our own field—for teaching, for research, for a review assignment—with pencils or highlighters in our hands, annotating as we go, so we can return to the most useful nuggets later. If you never read a book with no such implement within reach, you’re doing it wrong. Reading should often be a lark, an indulgence—not a chore or even a hunt for “useful” knowledge.

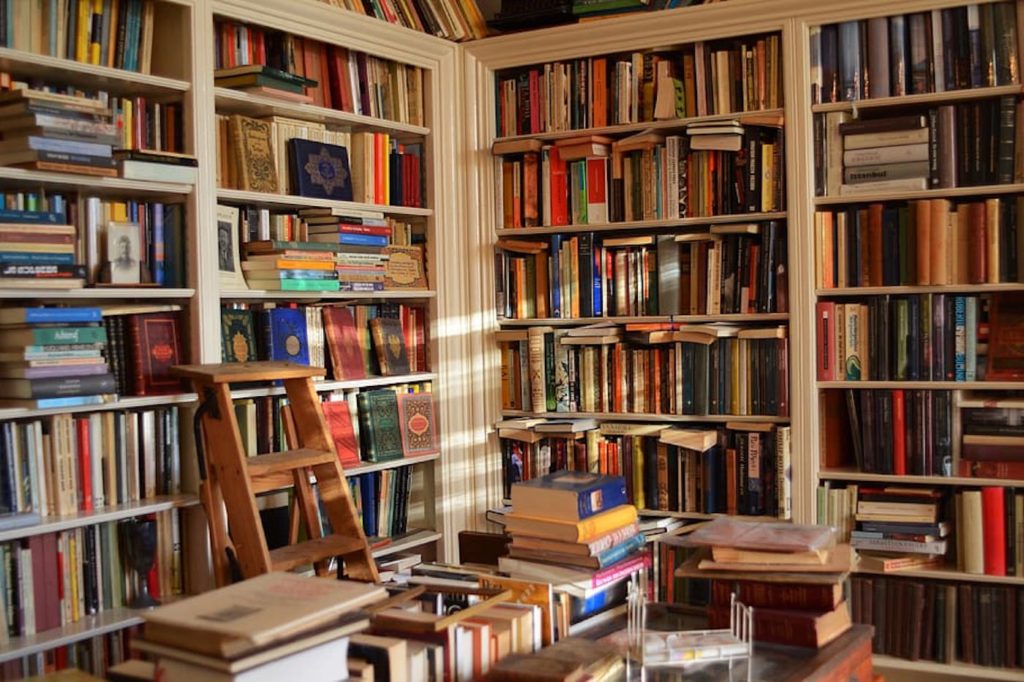

But which books to read? I want to work my way around to that indirectly, by first reflecting on my experience with getting rid of books.

When my wife and I moved from Virginia to New Jersey a dozen years ago, we gave about 500 books to our local public library for its used-book fundraising sales, and they were a small fraction of what we moved with us. Some of the books we donated were easy to part with—obsolete academic texts in our two disciplines, or works on the fringes of our own scholarly interests that we had used to teach courses we did not expect to teach again. Among our fiction, the culling principle was “we read it once, and don’t expect to reread it.” That accounted for scores of paperbacks in the mystery, science fiction, and thriller genres; no matter how much we’d enjoyed them, if we concluded that one reading was all a book was due, out it went.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.We still moved about a hundred boxes of books. And then started adding to our library again.

Several months ago I faced a harder task. I retired from full-time work and, with the loss of an office with its bookcases, had to consolidate my books at home. Even with the purchase of additional bookcases for the house, it was not possible to keep them all, and so I had to undertake another, more difficult cull of the shelves. My research and professional interests had widened and deepened over the years to encompass works not only of constitutional law, American politics and history, and political philosophy, but now also of intellectual and religious history, moral philosophy, and theology. How would I significantly subtract from all I had acquired over forty years? Especially since I intend to continue learning and writing as a scholar, how ruthless could I be?

Something akin to our earlier principle came to my rescue. We had once asked, “which are the books we’ve read but will not reread?” I now asked, “which are the books on which I will never rely for some fact, perspective, or insight in my own work?”

This worked—rather to my chagrin in some respects—wonderfully well. In my thirties and forties, busy with teaching and scholarship in political philosophy, constitutional law, and American politics, I had bought great quantities of secondary and analytical works in those fields, often taking advantage of the discounts offered by publishers at academic conferences to buy brand-new books. (To be frank, I bought books faster than I could read them. This is either the curse of all bibliophiles, forever behind in our reading—or the blessing, considering the well-stocked home library that our more judicious choices can produce.)

While the aid of others is valuable, there is no substitute for grappling with great works directly ourselves.

Now, compelled to consider real utility rather than “this seemed important once upon a time,” I was able to remove hundreds of books from my library and sell them to a used bookseller. Books I had once read, others I had foraged in for research, some others still quite unread—if they could not make a case for themselves as resources for real learning, out they went. Before I knew it, the bookcases in the house had some breathing room for new acquisitions. You didn’t think I’d stop buying books, did you?

This necessary culling compelled me, as you can see, to become more explicit about a principle that ought to guide our buying and our reading—but in my own case, had not adequately guided my buying years ago. Let me flesh out the implications with some general guidelines, bearing in mind that exceptions to each will be necessary.

First, always prefer primary sources to secondary ones. I don’t need all the commentaries I had collected on political philosophy, though some are keepers. I do want to hang on to the works of Plato, Xenophon, Aristotle, Machiavelli, Hobbes, Rousseau, et al. It is true that some great works do not reveal their depths to us without the aid of teachers, in person or in print, who have gone before us. I recall discovering a copy of Plato’s Republic in my grandmother’s house when I was in high school, and reading it on my own. I got much more out of it when studying it in a class as a college sophomore, with a professor who knew it well. But while the aid of others is valuable, there is no substitute for grappling with great works directly ourselves. A library can become cluttered with mere commentaries, which can be crutches on which we depend too heavily.

Similarly, in my own work in constitutional law, I have found that reading the opinions of John Marshall, who served as the fourth chief justice from 1801 to 1835, is an experience superior to reading any modern commentaries on his jurisprudence. I should know what I think about his opinions; it matters relatively little what others say about them. Constitutional law in particular is a field afflicted with an advocacy virus: too many books engage in ideological argumentation thinly disguised as legal or historical analysis. Time to clear them out, and read the cases for oneself.

This brings me to my second point, to prefer solid historical research to present-oriented “analysis” or polemics. This means generally avoiding books that address “current events” or “issues” of the moment. But even works that present themselves as history should be approached with caution. Authors who claim to present a historical account in order to address some contemporary concern almost invariably ill-serve both history and the present moment (think of the 1619 Project). Figures of the past wind up judged against more or less arbitrary standards of the present, and the present winds up being viewed through a selective historical prism that permits us to see only a sliver of the visible spectrum. History done well is concerned with understanding the past, not with addressing some problem of our own time.

History done well is concerned with understanding the past, not with addressing some problem of our own time.

Third, one should generally prefer old books to new ones. A book still in print after half a century—better still, after several centuries—has probably proved its value, even if it is only the value of influence, be it for good or ill. A new book may prove itself, but the odds are against it. Give it a few years, and let its reputation precede it.

I think this recommendation applies very strongly to fiction. In the last two years, I have read exactly one novel published recently, and though it was a critically acclaimed bestseller, it was a pretty flat disappointment, and I doubt the book will be available a generation from now. The time I’ve recently spent on Austen, the Brontë sisters, and Dickens has repaid me handsomely. If some small proportion of new fiction has legs for the long haul, we’ll know one day. Meanwhile Hardy, Trollope, Mann, and Tolstoy await.

Fourth, as I urged readers in a recent column, one should haunt used bookstores. Some books have gone out of print and should not have; others, even if in print, are undeservedly obscure and little known. The serendipity of used-bookstore discoveries is one of the greatest delights a reader can have.

Fifth, since newly published books are so numerous that some are bound to be of interest, one should read book reviews regularly. The weekend book sections of major newspapers, the back sections of major magazines, the quarterlies and other publications with Review of Books in their titles, and online reviews such as here at Public Discourse should be a regular part of our reading diet. Few indeed are the books I buy because of a review I’ve read, but adding to my library is only one reason I read book reviews. A negative review can alert us to a bad book—but so for that matter can a positive one, for the aim is not to be guided by the critic’s judgment but to be guided by the critic’s account to form our own. And a well-crafted review can serve as a highly condensed account of the subject treated by the book, sufficient to educate us in something worth knowing even if its 2,000 words do not prompt us to read 200 pages.

With all the time in the world, we might read all the good books we see reviewed. Since we cannot, it is worth our while at least to know what we can of them. I should add that this puts the onus on reviewers to do their jobs well, restating the thesis and argument of scholarly works or the plot and themes of novels sufficiently to tell us more than merely their opinion of the book or of what it treats.

In the end, discrimination is the thing needful. No reader can read all there is. We will all go to our reward with books unread that we intended to read. But there is more to the reading life than a duty to edify ourselves. Even the ephemera of our reading—those “I read that once” mysteries and the like that we leave behind when we move—have given us something of value if we have experienced the pleasure of a well-told tale. We must make time for the knowing of pleasure as well as for the pleasure of knowing.