Readers of this column who have clicked on the links I provide to books I mention will have noticed that most of them are from Abebooks.com, a website that originated in Canada as a clearinghouse for booksellers in many countries. Several years ago the site was purchased by the all-consuming behemoth Amazon, which must be gaining something from it. But I still link to it because it connects readers to sellers of used books who operate independently, posting their inventories and doing their own shipping.

I love these people. I’ve always been a sucker for used bookstores, and for any venue that features used books—indie bookstores selling both new and used books, public library sale rooms, you name it. On our honeymoon thirty years ago, my wife had to put up with my stopping at every used bookstore I spotted on Cape Cod—and there were quite a few then (whether there are still, I cannot say). On the way home to Virginia, our little Honda hatchback had so many books in the back that I was unable to use the interior rearview mirror.

A site like Abebooks is great for searching for a book one knows one wants. But a used bookstore! Browsing the shelves leisurely, one discovers books one never knew one must have. Even the smell is enticing, of old paper and leather and cloth. It was there on Cape Cod in 1992 that I discovered a boxed set of British Penguin paperbacks of Evelyn Waugh’s Sword of Honour trilogy (Men at Arms, Officers and Gentlemen, and Unconditional Surrender). I had read a little Waugh before this and enjoyed his wit, but these three novels of the progressive disillusionment of Guy Crouchback, a Catholic officer in the British army during World War II, were a revelation. Together they constitute Waugh’s greatest work, far better in my opinion than the somewhat lugubrious Brideshead Revisited (which I read later, and which suffered by comparison). Closely tracking Waugh’s own experiences, Sword of Honour captures the absurdity, futility, incompetence, and tragedy that invariably coexist alongside courage and daring in wartime.

A used bookstore! Browsing the shelves leisurely, one discovers books one never knew one must have. Even the smell is enticing, of old paper and leather and cloth.

Start your day with Public Discourse

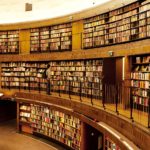

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.Twenty-five years later we were in Inverness, Scotland, and I spotted Leakey’s Bookshop (pictured above), a former kirk of the Church of Scotland packed with books on two stories, all higgledy-piggledy with nuggets of gold amid the dross. Here I found another book by Waugh, released just after the war—a first edition of When the Going Was Good, an anthology of excerpts from his pre-war travel books. Waugh’s travel writing is not as widely read today as his fiction, but it bears all his characteristic marks—a sense of the bizarre, a gimlet eye for the way the world works, and some of the most adroit and hilarious English prose of the twentieth century. Here is Waugh on preparing to be a war correspondent for a London newspaper, about to be sent to cover the invasion of Abyssinia by Mussolini’s Italy in 1935:

In the hall of my club a growing pile of packing cases, branded for Djibouti, began to constitute a serious inconvenience to the other members. There are few pleasures more complete, or to me more rare, than that of shopping extravagantly at someone else’s expense. I thought I had treated myself with reasonable generosity until I saw the luggage of my professional competitors—their rifles and telescopes and ant-proof trunks, medicine chests, gas-masks, pack saddles, and vast wardrobes of costume suitable for every conceivable social or climatic emergency. Then I had an inkling of what later became abundantly clear to all, that I did not know the first thing about being a war correspondent.

There at Leakey’s I also came across a first edition of The Yogi and the Commissar, a 1945 collection of essays by Arthur Koestler. Best known for his 1940 novel Darkness at Noon, a classic work on totalitarianism, Koestler was a former Communist who was chastened by direct experience of what his comrades were capable of. The Yogi and the Commissar collects a number of his wartime essays—though the final third of the book is fresh material. What is surprising about the book is that he managed to get it published in Britain before the war ended, given the fact that the Allies were still in league with Stalin’s Soviet Union. One might even say that Koestler’s work is one of the first salvoes of the Cold War, since he directly equates the “Fascist myth” and the “Soviet myth” as interchangeably evil, each one a top-down tyranny of “commissars” imposing on society by brute force, while claiming to be a regime of the people.

Koestler’s book of essays is dedicated “To Professor Michael Polanyi,” which is itself a clue to the author’s views. Polanyi—like Koestler a Hungarian emigré—would later be known for the concept of “tacit knowledge,” and for envisioning both the free market and the scientific community as generating a spontaneous order of information that defies the efforts of central planning.

In another of my used bookstore finds from long ago, Koestler’s 1973 novel The Call Girls, the idea of a free society spontaneously ordering itself through the discrete actions of individuals is conspicuously lacking, and I think that’s the point. This “Tragi-Comedy,” as Koestler calls it in his subtitle, features a dozen high-powered intellectuals (the “Call Girls”) convening in the Alps for a week to brainstorm their way to some consensus on solving the problems of war, human aggression, and overpopulation. They fail miserably, of course, chiefly because each one of these puffed-up academics (some with Nobel prizes) is determined to ride only his or her own hobbyhorse.

The chairman who brought them together, a famous physicist, wants to draft an “Einstein letter,” similar to the one Albert Einstein sent Franklin Roosevelt in 1939 to inform the president of progress being made in atomic fission, which is generally credited with being the germ of the Manhattan Project. But Koestler’s Call Girls are not trying to tackle a confined technical problem like the development of a nuclear weapon. The problem they have set for themselves is the remaking of human nature itself. Only the techniques of the commissar will do for such a task—and they will fail anyway. The arrogant intellectuals in this darkly funny tale only succeed in making themselves dispirited and ridiculous.

It is not attachment to causes, but the care of persons near to us, in whose lives we can make a difference, that is most important.

The same year Koestler published Darkness at Noon and Waugh saw action in Africa with the Royal Marines, Willa Cather published Sapphira and the Slave Girl, a novel I’d never heard of before I discovered a 1940s hardcover copy at a library book sale. Many students in American high schools have been required to read Cather’s My Antonia (though I somehow escaped this), and I had read O Pioneers! and Death Comes for the Archbishop, but this book was new to me. Sapphira is set in the countryside near Winchester, Virginia (where Cather lived until the age of nine, when her family moved to Nebraska) just a few years before the Civil War, and centers on the household of a miller, his wife, and her slaves, against one of whom the mistress conceives an unreasoning jealousy.

One cannot say there is any politics about this simple story, so simply and beautifully told. But perhaps that is Cather’s point—that it is not attachment to causes, but the care of persons near to us, in whose lives we can make a difference, that is most important. I do not expect this novel to be assigned in high schools, since it is full of the voices of Virginia in 1856, white and black alike, with the “n-word” frequently used. But that’s rather a shame, for like Twain’s Huckleberry Finn, which is similarly marked by language that makes many readers recoil, this is a humane story of deep relationships and the struggle for justice—for this person, right in front of us.

Each in his or her own way, come to think of it, Waugh, Koestler, and Cather represent this most precious impulse of twentieth-century literature: that every life that comes within our reach has its claim on us, and is not to be wasted or sacrificed to any cause, program, or system on which we have the conceit to place a higher value.