In our April Long Read, “The Family Policy Imperative,” Gladden Pappin argued that conservatives need to propose and enact concrete policies that direct the state’s economic resources toward families. Yesterday, we published an article by Lyman Stone critiquing Pappin’s analysis of Hungarian social policy. Today, we present three shorter responses to other aspects of Pappin’s argument.

First, Kelly Hanlon argues that Pappin fails to account for technological improvements that will counteract a shrinking labor force, and that he is too optimistic about the government’s capacity to administer economic programs that will not undermine family formation. Second, James Harrigan and Antony Davies caution conservatives against adopting a progressive vision of government. Finally, Daniel Burns argues that our country’s declining fertility is not fundamentally an economic problem and will not be solved by wealth transfers.

To Encourage Family Formation, Seek Long-Term Economic Growth

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.Kelly Hanlon

A fundamental assumption of Gladden Pappin’s argument is that a shrinking labor force will diminish long-run economic growth. He argues that this reduction in the labor force will be a permanent feature of the future economy. To support his claim, Pappin reasons that a reduction in the supply of labor will cause the demand for existing labor to increase, thereby creating inflationary pressures on wage rates. Because of increased wage rates, Pappin expects that family formation and fertility rates will continue their current downward trajectory, as young people choose to work instead of raising families during their childbearing years.

Pappin’s policy proposal—to increase federal spending to incentivize family formation—rests on the faulty assumption that future economic growth is dependent only on the size of the labor force. In reality, economic growth depends on a combination of capital stock, labor stock, and technological progress. Moreover, the labor stock does not simply comprise the number of able-bodied workers. It also takes into account the effectiveness (or efficiency) of labor. One need not look very far for examples of increased market efficiencies and growing economies spurred on by technological improvements.

Nobel Prize–winning economists Robert Solow (1956) and Paul Romer (1990) both point to the interplay between population growth and technological progress in long-run economic growth. Pappin is right: a shrinking population will lead to a smaller workforce. But because he does not address the potential for labor to become more effective or for other technological changes to contribute to economic growth, we cannot take seriously his claim that the singular way to ensure long-run economic growth is by instituting a new federal family policy.

Economists have long examined the components of growing economies, and the conservative movement has largely subscribed to a suite of policies—the rule of law, protection of private property, and limited government—that have the greatest potential to encourage long-run growth. Because the government does not create wealth (it can only redistribute existing dollars or print new ones), all increases in government spending must be offset by increased taxes today or tomorrow. This is a simple and uncontested fact of government spending. Pappin’s policy proposal essentially writes off its potential costs without offering a solution for how to pay for such a plan.

Family formation should continue to be one of the central planks of the conservative movement, but we must focus on rebuilding the twin institutions of marriage and family without government intervention or interference. In the United States, government programs have little—or no—track record of actually achieving their stated aims, and, once established, welfare programs are very hard to end. Where government has involved itself in the family, it largely has worked to destroy what social conservatives would recognize as the traditional family.

For example, Amity Shlaes has detailed the destruction wrought in historically black communities with the introduction of LBJ’s Great Society programs. These policies were meant to help black families, but their unintended consequences actually led to their demise. Here at Public Discourse, Rachel Sheffield points out that welfare policy destroyed incentives to work and marry, two of the main defenses against poverty. Pappin doesn’t address the potential for unintended consequences resulting from another expansion of federal spending directed at American families, but the historic failure of such programs is appalling.

In the end, economic policy should focus on the promotion of long-run growth, which will increase the standards of living for all Americans. Social conservatives should look to the intermediary institutions of civil society—not to national economic policy—to encourage marriage and family formation.

Family formation should continue to be one of the central planks of the conservative movement, but we must focus on rebuilding the twin institutions of marriage and family without government intervention or interference.

What Happened to Conservatism?

James Harrigan and Antony Davies

Gladden Pappin offers a two-step argument that begins with a misreading of American birth rates and ends with a call for increased governmental intrusion into American family life. This he does in the name of conservatism.

This is brave new territory for conservatives. It wasn’t all that long ago that they did everything they could to limit governmental power—and rightly so. When it comes to proposals like Pappin’s, those who seek to preserve the liberty of the American people should proceed with caution.

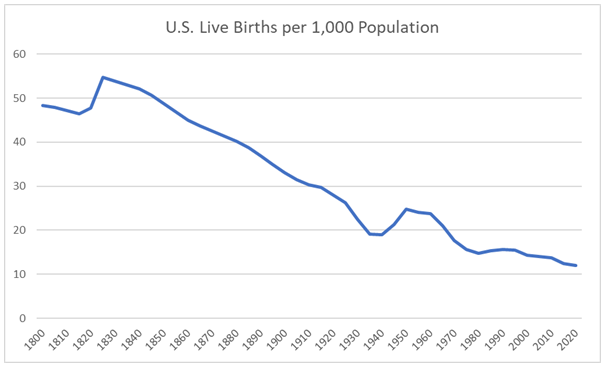

The problem with Pappin’s analysis is obvious from the first line. “Conservatives,” he writes, “need to start thinking of children as an investment in our economic future.” We have, he opines, treated children for too long as a cost, and we will need to reorient our thinking. But the truth is, the American people have used their natural freedom to act in their own interest. What has this led to? Declining birth rates. Since 1825.

Data source: Statista

American birth rates have declined so precipitously precisely because American families have been doing what Pappin says they should do: they have been treating children as an investment. They’ve simply come to a different conclusion from what he’d like.

By their actions, it’s clear that Americans have determined that children are not the good investment Pappin believes. For the past two centuries, the return on children-as-investment has been declining because automation and improved standards of living have made it unnecessary for children to work. Meanwhile, the cost of raising and educating children has been steadily rising. Pappin regards children as a good investment and wants Americans to have more of them. But the declining U.S. birth rate that Pappin decries exists precisely because Americans have spent the past two hundred years coming to the conclusion that children are poor investments.

Pappin concludes that Americans are simply wrong—that we need more children to support the elderly—and he proposes using the force of government to correct Americans’ collective error. If there were positive externalities associated with children, Pappin would have an argument. But he identifies none. Instead, he talks about children as being essential for “the common good”—a term social engineers apply when they want to override other people’s preferences with their own. If we were to substitute “healthcare” for “children,” Pappin’s argument would look like a major plank of the Democratic Party. Is this what we’ve come to, that the difference between conservatives and liberals lies merely in the ends to which they apply the coercive force of big government?

“One common denominator of American conservative politics,” Pappin writes, “has been a commitment to growth. Cut taxes and liberate businesses from onerous regulations, the argument goes, and the American economy will resume its commanding position in the global growth tables.” But where do we find conservatives like this?

The truth on the ground is telling. Donald Trump added an average of 62 economically significant federal regulations each year of his presidency. That’s the same rate as Barack Obama’s. George W. Bush added an average of only 45 per year, but that’s the same rate as Bill Clinton’s. Federal tax receipts as a fraction of GDP averaged 16.7 percent during the Trump administration versus 16.2 percent during the Obama administration. Since the Carter administration, Republican presidents have collected an average of 17.3 percent of the economy in federal taxes, versus 17.5 percent for Democratic presidents. That’s hardly a commitment to cutting taxes. Over the same period, the economy grew an average of 2.4 percent faster than inflation under Republican presidents versus 2.9 percent faster than inflation under Democratic presidents.

Whatever commitments Republicans claim to have to economic liberation, the evidence indicates that they are achieving less than are Democrats. Given this history, combined with four years of Trump populism, we might have to admit that the conservative movement in the United States is moribund.

So what’s the difference between progressives and Pappin’s brand of big government conservativism? Not much. And if conservatives follow his lead, it will be still less.

The Difficulties of Crafting Pro-Family Economic Policy

Daniel Burns

With Dr. Gladden Pappin, my colleague in the University of Dallas Politics Department, I am in full agreement that conservatives need to think more creatively about how to craft policies that support American families. We disagree on how easily this can be done.

Pappin points to Hungary, arguing that whatever policies overcame its terrible post-Communist fertility depression must be particularly good examples of pro-family policy for the United States to imitate. But the unusually dire fertility situation of pre-2011 Hungary makes it a weak example for our own country, not a strong one. Even if some policy decisions may have helped a small nation-state recover a modicum of optimism after decades of tyrannized hopelessness, we would have no reason to assume that those same decisions could also slow a great liberal empire’s long decline into decadence. After all, despite its recent bump, Hungary’s fertility rate remains even lower than ours today.

And why are the citizens of wealthy countries like ours voluntarily infertile? As the great cultural critic Joseph Ratzinger often argued, Westerners’ rejection of children is a symptom of their profound despair about the future, deriving from a general loss of faith in any higher purpose beyond comfortable self-preservation. This is not fundamentally an economic problem and will not be solved by wealth transfers.

With Dr. Gladden Pappin, my colleague in the University of Dallas Politics Department, I am in full agreement that conservatives need to think more creatively about how to craft policies that support American families. We disagree on how easily this can be done.

To the contrary, our society’s extraordinary wealth has been a major culprit in fracturing the concrete, transgenerational communities that foster the natural human desire to participate in the great cycle of birth and death. Since more wealth transferred to our remaining American parents will not automatically rebuild those communities, it is unlikely to jumpstart that cycle.

In addition, our ever-growing wealth has given us the cultural expectation that our children deserve—and should probably not be born until we can secure for them—a living standard beyond our great-grandparents’ wildest imaginings. If we now shift tax dollars to parents so that their living standard rises even higher, then within a generation or less, we can expect cultural expectations to absorb this change. This will mitigate or erase any hoped-for relief from all those financial stresses of child-rearing that (according to polls) appear to be scaring off some potential parents. Such stresses are always relative to our cultural expectations.

Neither here nor in his original proposal at American Affairs does Pappin offer concrete evidence, beyond the weak example of Hungary, that his parental subsidies would lead to any significant change in Americans’ fertility decisions. This point bears emphasis. Pappin’s entire argument for a new trillion-dollar government program is that it is needed in order to address the American fertility crisis, yet he offers no evidence that it will do anything like this. After alluding in his American Affairs piece to some of the type of concerns I have just raised, he rejoins that, “Nevertheless, incentives matter.”

I would support any incentive that, for a cost proportionate to its benefits, actually helped Americans have more of the children that they still tell pollsters that they wish for—even despite their continued aversion to the sacrifices that those children would require (a fact that polls hardly capture). Finding such incentives is not easy. Our federal government already subsidizes housing, healthcare, childcare, and higher education, yet a large portion of these subsidies gets absorbed when market prices rise in response.

Pappin also argues that family-subsidy policies “are important as an indication of what a society considers worthy of support.” In other words, he seems to believe that we encourage public respect for certain causes when we show that we value them enough to spend other people’s tax dollars on them. But recipients of other federal cash welfare benefits do not generally regard these as a sign of public respect for their life decisions.

Moreover, we have already tried a massive experiment like the one Pappin proposes. In order to show how highly we value our elderly parents, we decided in 1966 to have the federal government pay their medical bills instead of forcing them to rely on their own adult children for support. The result has not exactly been higher levels of public respect for elderly parents.

Under Pappin’s proposal, precisely if the new family payments were not simply absorbed either by market prices or by cultural standards of living, many fathers would suffer a fate similar to what adult children have suffered under Medicare. Their previously necessary role as providers would be made superfluous by governmental generosity. This is not what our nation’s men (especially in the working class) need in the midst of an ongoing and nationwide crisis of masculinity. And since our fertility decline appears itself to be largely caused by the decline of marriage, we may end up with even fewer babies in the long run if we further erode marriage norms by making fathers appear less necessary.

Pappin says that his proposal shows the need for “direct, government-driven measures ordered to achieve outcomes in accordance with the common good,” and for policy entrepreneurs with the “imagination to set a goal and pursue it.” I would suggest instead that it shows the danger of employing platitudes of this kind within policy debates, where good intentions should be assumed rather than showcased, and where the hard work always lies elsewhere.