Read the responses to this article by Lyman Stone, Daniel Burns, Kelly Hanlon, and James Harrigon and Antony Davies.

Consider a moment in the not too distant future. The global COVID-19 outbreak is a distant memory, but the generation affected by it is only now coming of age. The regimen of online learning and social distancing wasn’t quick to fade, even though the virus petered out soon enough. While most adults had returned to normal life, children had no other conception of what “normal” was. When schools returned, students who were ten could no longer remember life before masks and social distancing. In the pivotal years for learning human interaction, they had plunged headfirst into the online world; they set a new standard for the meaning of “digital native.” And now that ten years had passed by, the cohort whose adolescence had been locked down were at their debut. To everyone who watched them, the truth was painfully evident. They did not know who they were; they did not know where they were from; they did not know what to say; they did not know what to do.

Already today, in 2021, there is talk of a post-coronavirus “baby bust”—not simply because of economic collapse but also because of the collapse of human interaction, the suspension in many places of socializing, festivals, and countless other elements of the natural human background. For a certain sector of economic actors, these changes have been beneficial, indeed positively good. Kept in their houses, people have no option other than to consume media and communicate through social media platforms, while ordering food and consumer products online for delivery. None of the changes to our way of life in the last year fosters the family formation that modern society depends upon for future economic success.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.At the same time, the home itself has become more economically important. Once a place to rest one’s head, the home has become a workplace as well as school. While many industries expect to bring their workers back to the office, the trends toward remote work and distance learning were rapidly accelerated. As Michael Lind observed last fall, this shift offers a rare opportunity for reorienting American economic growth, at least partially, around family-centered and home-centered activities. Whether we like it or not, the trend toward working from home accelerated over the last year, and even a significant recovery in normal, office-based working conditions will still leave us with a substantial shift in the work-from-home direction.

For social conservatives who value home life, this moment thus presents one of considerable opportunity—and responsibility. Yet the normal conservative instinct, particularly in policy matters, is to preserve or tweak existing arrangements in a piecemeal way. In a normally functioning political system, such an approach has much to recommend it. But the experience of the last ten years should have taught conservatives to look a few years ahead. Criticisms of American economic policy, and especially trade policy, were outré a decade ago. Today, many are now taken for granted. Even so, conservatives still have not “reset” their approach to economic and cultural policy with a more forward-looking vision. Much as conservatives like to make fun of “five-year plans,” that is exactly what they need to offer.

Whether we like it or not, the trend toward working from home accelerated over the last year.... For social conservatives who value home life, this moment thus presents one of considerable opportunity—and responsibility.

Labor Pains

One common denominator of American conservative politics has been a commitment to growth. Cut taxes and liberate businesses from onerous regulations, the argument goes, and the American economy will resume its commanding position in the global growth tables. When we consider overall economic growth, however, economists typically point to two drivers: technological advance and growth in the labor force. A growing population demands strong economic production, while also being available to contribute to that production. An aging population is averse to risk, hoards wealth, offers less dynamic labor, and generates a caretaker economy. How we want our country to look on that score depends heavily on the choices that we make in the next few years.

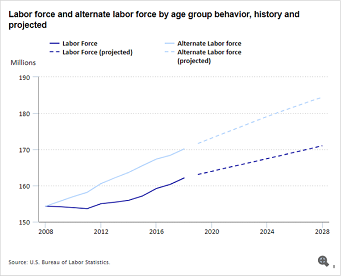

A recent report from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) highlights the problem. Already for the last twenty years, growth in the U.S. labor force has been decelerating under the combined pressure of declining female participation in the labor force plus steady retirement out of the baby boomer cohort. Between 2018 and 2028, the population aged 65+ will grow by a rate more than seven times that of the 16–54 cohort. By 2028, the BLS projects that over 25 percent of the population will be 65+. The share of the population aged 16–54 will drop from a recent high (1988) of nearly 75 percent to a multigenerational low of around 60 percent.

With an expanding cohort of older Americans and a slower-growing cohort of young Americans, the gap between our usual labor force participation and actual labor force participation will continue to widen. The BLS benchmarks this scenario by projecting what would have been the American labor force if the relative contributions of age cohorts had remained steady even after 2008, when baby boomers became eligible for Social Security.

As the BLS chart indicates, shifts in population distribution will skew our labor force well away from where it might have been, based on the continuation of trends prior to 2008. By 2028, the BLS expects the gap between actual and typical labor force participation to rise to 13 million, or nearly 8 percent of the labor force. In short, our labor force will only grow more skewed—toward the elderly and with a falling percentage of youth participation.

These projections of a strained labor market do not even take into consideration the added possibility—now reality—of a baby bust. Ten years from now, it is these trends that will be driving political change in developed countries. The gravity of the lockdown-related baby bust is almost impossible to overstate. According to the Brookings Institution, 2021 births will show a year-over-year drop of three hundred thousand, an 8 percent drop in the United States, which recorded 3.7 million births in 2019. Early reports from European countries show even more marked drops, with January births in France down 13.5 percent year-over-year, and December 2020 births in Italy down 21.6 percent year-over-year.

For the immediate future, from an electoral standpoint, those choices have already been made. After four years of populist Republican administration, it is now a Democratic administration that has extended to families, beginning July 1, a monthly per-child cash benefit designed to acknowledge the crucial role that child-rearing plays in the economy as a whole. From the standpoint of long-term economic growth, support for childbearing families is a direct investment in the economy of the future.

While some conservatives have sought to envision pro-family spending policies as a form of reciprocal social insurance, drawn out by young families only to be repaid by their later financial success, the family is now a more urgent and more direct investment priority—beyond levels that can be understood through frameworks such as mutual insurance.

From the standpoint of long-term economic growth, support for childbearing families is a direct investment in the economy of the future.

The Great Reversal

Conservative objections to large-scale family policies, as with large-scale spending programs of any sort, typically begin from worries about the consequences of accompanying fiscal expansions. In the wake of the bank bailouts during the 2008 financial crisis, for example, many conservatives predicted that a tidal wave of inflationary pressures would be released on the American economy, or that our children and grandchildren would be burdened for generations by the need to “pay off the debt.” While large-scale fiscal expansions can lead to inflation, my purpose here is to put forward a different inflation-related consideration (for more on the potential inflationary consequences of family policies, see my post at the Harvard Law Review blog).

Without strong national policies aimed at encouraging family formation, we will soon see firsthand what a dramatically weakening young labor force causes economically, socially, politically, and culturally. What we are looking at in post-coronavirus labor markets is something very different.

The celebrated British economist and central banker Charles Goodhart has recently predicted that the aging of Western societies, combined with continued globalization pressures, will constitute what he and coauthor Manoj Pradhan call The Great Demographic Reversal. Western societies, they observe, are quickly reaching an inflection point in terms of their productive and dependent populations. Both older and younger populations, consuming more than they produce, place inflationary pressures on economies. As our elderly populations increase and place more demands on the economy, the share of the working-age population, now even smaller due to recent downtrends in fertility, will continue to fall. While conservatives like to complain about dependency on government, a shrinking working-age population and increasing population of elderly (who will have saved less than their forebears heading into retirement) will sharply increase what economists call the “dependency ratio.”

Normally, an aging population would be able to obtain support for elder care through tax increases on young workers. But, as Goodhart and Pradhan note, declining fertility impacts this dynamic as working-age population growth begins to slow. “Labour scarcity,” they note, “will put them in a stronger bargaining position . . . to bargain for higher wages. This is a recipe for recrudescence of inflationary pressures.” While a growing working-age population normally has some deflationary pressure, as workers pocket excess income, an increasing elderly population and slower-growing working-age population will together add inflationary pressure to the economy.

Why this is the case is intuitive. An elderly population needs to consume without producing. Therefore, younger people of working age must provide for their own consumption and for the consumption of the elderly citizens. As the number of those in the working-age population shrinks relative to the elderly population, the workers find themselves in higher “demand.” This results in an increase in the “price” of these workers—that is, their wages. Since wages are the largest cost in the production process, this higher cost is passed on to consumers in the form of prices increases: inflation. The more elderly people relative to workers, the more the price pressures build, and the more dramatic the inflation.

This shift would not merely be another ho-hum change in overall economic balance. For much of the last thirty years, the world economy has benefited from a large increase in labor supply through China’s modernization, as well as from the initial postwar increase in women’s labor force participation (which has now declined). Deflationary pressures have easily stayed below central bank targets, the prices of manufacturing goods have fallen, and interest rates have fallen to historic lows. While the last thirty years have also been a period of worsening inequality and recently of rising populism, most policymakers do not take account of the underlying demographic structure that has enabled recent political economy to function at all.

What Goodhart and Pradhan describe instead marks the “Great Reversal”—a dramatic change in each of the fundamental, underlying conditions of the economy of the last generation. A demographic reversal in Western economies will lead to sharply higher inflation, rising interest rates, reduction in personal savings and investment, severe intergenerational political tension, and a return of tension between fiscal and monetary policy. “Neither financial markets nor policymakers,” they note, “are prepared for a significant rise in inflation and wages, or a rise in nominal interest rates.” Since most policy discussions involve only a two- or three-year window, analysts typically do not anticipate the long-term consequences of underlying market conditions.

A demographic reversal in Western economies will lead to sharply higher inflation, rising interest rates, reduction in personal savings and investment, severe intergenerational political tension, and a return of tension between fiscal and monetary policy.

Disincentives toward Family Formation

Each of these negative trends was already in place even before the response to the COVID-19 pandemic plunged the world into an economic shock of epic proportions. Considered in light of already-impending labor market declines, the decisions of the last year can only be seen to have rapidly accelerated the path toward lower growth, higher inflation, and potentially fatal stresses to the economic architecture of modern societies.

The generation of children subjected to this year’s lockdowns, those coming of age and making their initial “life decisions” over the next ten years, will thus face unprecedented headwinds. Although demand for labor will increase as demographic trends accelerate, long-term planning has become more difficult than ever. Reasons not to marry and not to have children will suggest themselves at every turn. Delayed marriage and delayed childbearing will likely grow worse.

Disincentives toward family formation result directly from the underlying economics. If working-age people find themselves in higher demand to work, and are incentivized by higher wages, they will likely focus less time on having and raising families. This will only make the crisis worse and worse as time goes on.

Many conservatives tend to assume that economic outcomes in capitalist economies are “natural.” Yet there is nothing less natural than severing the connection between economic growth and family formation. For millennia, human beings have viewed children as an asset, not a cost, for the simple reason that children provided additional labor and looked after their parents in old age. It is only in the last century that this link has been severed.

We now have a system that forces would-be parents to think of their children as a cost and not an asset. Yet these children are quite literally the most valuable asset that any country could possibly possess. Without children, a society withers and dies while its economy is converted into something resembling a chaotic nursing home, where a shrinking workforce slaves away to service a growing pool of retirees (as the specter of forced euthanasia lurks in the background).

Bear in mind that the labor market squeeze from adverse demographics was already in place before the lockdown era began. With family formation and childbearing rates cratering across the developed world, and with more aggressive fiscal responses required to offset catastrophic economic damage, the coming era will be, as Goodhart and Pradhan conclude, “nothing like the past.”

Every aspect of our lives will be impacted. Saving for the future will be difficult and chaotic. Intergenerational war over resource allocation will become normal. Asset prices will boom and bust as older savers plow more money into property markets, further pricing out younger workers. Political systems will destabilize.

Reasons not to marry and not to have children will suggest themselves at every turn. Delayed marriage and delayed childbearing will likely grow worse. Disincentives toward family formation result directly from the underlying economics.

Tankers and Dinghies

Faced with impending macroeconomic problems of the scale now before us, most proposals coming from right-leaning thinkers are insufficient to “conserve” robust family life. In countries that face not merely slowing growth but an absolute decline in their labor forces—as Germany, Italy, and Spain face, among others—righting the ship will take more concerted action than before. Since these problems are ones confronting advanced economies as a whole, Americans will have to take a look outside the borders of the United States for ideas on how to confront them. (I leave aside, for the moment, the unequivocal teaching of the popes in favor of a family wage.)

Right-liberal economists averse to state intervention typically want to know what small-scale interventions within their limited toolkit would help get American family formation back on track. Unfortunately, such an approach is doomed to fail: limited approaches to family support will not be compelling at the ballot box, and will almost certainly be inadequate to the challenge of boosting American family life. At the national level, our demographic course is akin to that of the tanker recently stuck in the Suez Canal—a gigantic array of valuable goods that, once it runs aground, cannot be set back on course by sending a few dinghies its way.

The best versions of the reformist approach, like Oren Cass and Wells King’s Family Income Supplemental Credit, offer significant benefits for working families of several children, and help to move the window of conservative discourse further in the direction of state action. But beginning with an intentionally limited goal—merely “smoothing income and expenses over a family’s lifetime,” in the case of FISC—eventually leads to limited policy.

Faced with impending macroeconomic problems of the scale now before us, most proposals coming from right-leaning thinkers are insufficient to 'conserve' robust family life.

Learning from Hungary’s Example

One country whose escape from a demographic death spiral has now become better known is Hungary. When Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz party came to power in 2010, Hungary’s birth rate had fallen every year since the mid-1970s, and the country was losing overall population at a significant clip every year. Rather than picking an abstruse goal like smoothing lifetime family expenses, Fidesz openly made the promotion of family life and childbearing the sine qua non of its domestic policy agenda. Rather than viewing national spending on families as something to be minimized, or rationalized as a mutual insurance scheme, the government made its stated goal to increase family expenditure each year. Hungary now boasts an annual national outlay of 5 percent of GDP on families.

In the United States, conservatives often worry that family benefit schemes provided outside the context of a conservative family culture would somehow be counterproductive. Such concerns were not foreign to the Hungarian approach. Indeed, Fidesz came to power in 2010 with a fertility rate far lower than that of the United States—a far more difficult cultural situation. Rather than punt on family benefits, though, the Hungarian government launched a larger set of initiatives to shape cultural norms around family life.

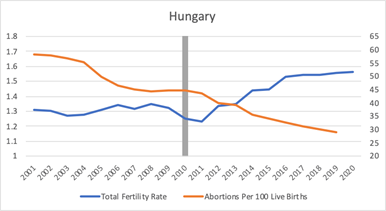

Since 2010, when the Orbán government started its family policy, the total fertility rate in Hungary has increased 28 percent. Prior to 2010, abortions per hundred live births had stabilized at around forty-five after falling from enormous numbers during the Communist era, when abortion was effectively used as a form of contraception. According to Hungarian government statistics, after the family policies came online, abortions fell by a further 35 percent.

(Chart credit: Gladden Pappin. Data sources: European Union (TFR 2001–2019); Hungarian Central Statistical Office [TFR 2020; abortions].)

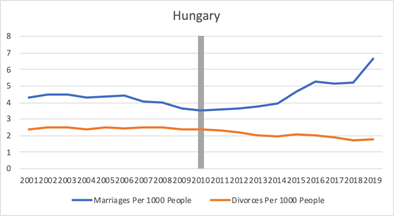

Following the beginning of its family policies in 2011, Hungary has experienced a marked improvement in its marriage rate as well as a decline in divorce. Since 2010, marriages per thousand people have increased by a staggering 88 percent, while divorces have fallen 25 percent.

(Chart credit: Gladden Pappin. Data source: Hungarian Central Statistical Office [marriages; divorces].)

Hungary stands out against the trend of its neighbors. Between 2010 and 2017, marriage rates in the European Union remained static at around 4.4 per 1,000 people per year. Yet in Hungary they rose from 3.6 to 5.2, an enormous rise of 45 percent. In this time period, divorces also remained static in the European Union at 2 per 1,000 people per year. Yet in Hungary they fell from 2.4 to 1.9, a fall of 21 percent. Clearly Hungary is bucking the European trend.

Nor was this a regional phenomenon. Consider Hungary’s five closest postcommunist neighbors: Romania, Croatia, Serbia, Slovakia, and Slovenia. The average increase in the marriage rate in these countries between 2010 and 2017 was only 11.5 percent, versus 45 percent in Hungary. At the top of the list was Romania, which clocked in a 28 percent increase. But when we expand the window with a supplementary national dataset, Hungary still beats Romania by a long shot. After 2017, the marriage rate failed to rise any higher in Romania, meaning that as of 2019 it had only risen 28 percent from its 2010 base. Meanwhile in Hungary, between 2010 and 2019 the marriage rate rose an enormous 88 percent. Whatever way you cut the numbers, Hungary is an extreme outlier when it comes to its increasing marriage rate.

Financial family policies are not the only element of Hungary’s approach, however. Katalin Novák, the minister charged with overseeing Hungary’s pro-family initiatives, explained to me at a meeting in December that pro-family education has been an integral part of Hungary’s family initiatives. Schoolchildren are taught, at an appropriate age, about the family benefits available to them should they choose to form families. The very fact of having a government ministry devoted to family affairs also sets the tone on a national level. Rather than excluding family benefits due to cultural problems in their administration, American conservatives should propose both family benefits and corresponding pro-family education promoted at a national level.

Whatever way you cut the numbers, Hungary is an extreme outlier when it comes to its increasing marriage rate.

Marriage and Children Are Essential Elements of the Common Good

It was for the sake of living well together, said Aristotle, that “marriage connections arose in cities, as well as clans, festivals, and the pastimes of living together.” Such elements of the tapestry of ordinary life, he added, are “the work of affection,” which (elsewhere in the Politics) he supposes “to be the greatest of good things for cities.” In our modern regimes, no state is at risk of taking a heavy-handed approach to promoting family life. But a robust structure of family-related benefits, integrated into national life and made integral to national education, would help to attain one of the essential elements of the common good, while relying on the personal decisions that remain the stuff of modern life.

If such a dream seems far off, it is perhaps only because American conservatives have lacked the imagination to set a goal and pursue it. Until about three months ago, the prospect of direct family benefit payments was rejected out of hand by many on the right as a pipe dream. But beginning this summer, it will be a reality—albeit one brought about by the initiative of Democrats, who snatched the issue away from Republicans after four years during which the GOP could have advanced the cause on its own terms.

Conservatives have long been obsessed with the “supply side” of the economy. They have seen investment in new factories and new technologies as key to economic growth. It is true that, in the long run, economic growth is determined in part by technological change. But far more important than technological change for economic growth is growth in the labor force. A shiny new factory is useless if there are no workers to man it. Conservatives need to start thinking of children as an investment in our economic future. Families, too, need to start thinking of children as an investment and not a cost—as they did in the past, when children were employed in farm work. The only way to do this in the modern economy—an economy that has severed the age-old link between children and additional labor—is by ensuring that economic resources are directed toward families by the state.

When the direct payment funds run out after the end of this year, the stage will be set for considering which proposals are likely to carry the day. As conservatives know (since they have made a mantra of the point), government programs, once begun, are difficult to repeal. Checks in hand make an extraordinary material and psychological difference to ordinary Americans. Indeed, in a recent survey administered by American Compass, families made clear the need for direct financial support in order to realize their childbearing goals—as well as their strong preference for support in the form of direct payments. Once the rollout of direct payments occurs this summer, it is far likelier to be extended rather than repealed. The ground will thus be set for those on the right who can make a proposal for administering and extending family benefits on conservative terms.

A robust structure of family-related benefits, integrated into national life and made integral to national education, would help to attain one of the essential elements of the common good, while relying on the personal decisions that remain the stuff of modern life.

Five-Year Plans

The global response to the COVID-19 pandemic has dramatically accelerated the problems facing those on the right who would, if in government, wish to orient political and economic life in a way beneficial for the traditional family. Yet much of the discussion among conservatives chugs along as though the only thing needed were a small financial boost to help families get over the hump of early-stage child-rearing.

Let us return to the situation likely to face us, now that we have spent more than a year ensuring that existing trends against family formation and childbearing will accelerate at a dramatic rate. This young generation, coming of age and soon to come of age, is the one we have kept in the back of our minds throughout these considerations. Even before the year of lockdowns, they were likely to be a cohort that would marry later than their parents, form smaller families, and even, before all that, date less and interact less with members of the opposite sex. Now they face, on top of that, the confused reorganization of global economic life, isolation from their peers, and a media and cultural apparatus weaponized against traditional family life.

Must this generation also be fated to suffer a lack of fiscal support from its own supporters—pro-family conservatives? Unfortunately, if the muted response to family policy proposals on the right is any indication, the answer is yes.

That does not have to be the case. For conservatives who claim to be on the side of long-term growth, there is no model available other than fostering robust technological growth as well as labor growth. Within the realm of conservative goals, there is no major policy lever to pull in that area other than pro-family policy. Conservatives who balk at generous fiscal supports due to the threat of “inflation” can now consider, thanks to Charles Goodhart’s Great Demographic Reversal, that the greater threat of inflation comes from lack of political action.

Elsewhere, I have proposed a national family benefit target of 5 percent of GDP, a proposal that could boost domestic manufacturing. I have also argued for the incorporation of key elements of the Hungarian program: a program of generous loans forgivable throughout the course of childbearing, and a national home mortgage subsidy to soften that major obstacle to home formation. Michael Lind’s family proposals stem from a similar view of the problems currently facing the American economy and society.

More than proposals alone, conservatives need to change their way of thinking about politics in order to grasp and address the problems now facing Western societies. In the near-term future, it is possible that a few conservatives can still meet with political success, perhaps at the local or state level, by preaching the modern American conservative message of limiting government spending and lowering taxes. Now that the Biden administration has partially co-opted family policy while most Republican politicians simply stood in the way, the political outlook for pro-family conservative politicians is not straightforward.

One thing, however, is clear. Given the acceleration in downward demographic trends, it is time for conservatives to stop thinking about tweaking 1990s welfare reform or rerunning the Trump platform, and time instead to position themselves to answer the extraordinary strains Western economies and societies will face in the five or ten years to come. To do that, they will have to reorient themselves and begin governing in the tangible, immediate interest of American families. Unless they do so, a set of economic and social problems is likely to emerge that will make it difficult for them to gain power again.

The name of the next conservative agenda is already clear. It is the family imperative.