There is growing agreement among many of us who see the family unit as the bedrock of society that the United States must do more to support families, and that “doing more” is going to have to involve a lot of policies that conservatives have historically been hesitant to adopt. Without greater willingness to directly support family formation, Americans will face a demographically foreshortened future: poorer, less equal, and lonelier.

So, in his recent article for Public Discourse, to which I have been invited to make a response, Professor Gladden Pappin is absolutely right to call for a new vision for conservative policy and forthright support for family formation. His prior proposals for large and generous income transfers to families with children are part of a wider range of conservative calls to cast aside the destructive legacy of work-worshipping, corporation-dependent conservative politics. And as corporate executives increasingly use their economic clout to impose a social vision hostile to conservative priorities, this call becomes even more urgent. For all these reasons, Pappin’s piece is a welcome contribution.

For many years, social conservatives wrongly ceded economic policy to those with absolutely no interest in conservative social priorities. Today, in a twist that a decade or two ago would have been unthinkable, conservatives have become preposterously enamored of the most peculiar of all policy leaders: Hungary. Social conservatives of all stripes have caught the Viktor Orban fever, and can’t say enough good things about the Hungarian government. It helps that the Hungarian embassy hosts events with a lot of conservative writers given speaking slots and dinner, and that when conservative intellectuals visit Hungary, they enjoy relatively easy access to officials.

There are also good reasons conservatives would be predisposed to think well of Hungary these days. Orban’s government enshrined the married family unit in the nation’s constitution, and has implemented numerous policies explicitly aimed at conservative priorities such as reducing the abortion rate, encouraging marriage, and increasing fertility. Orban has firmly opposed high rates of immigration, especially irregular, unregulated, or illegal immigration. For all these reasons, the affinity between American conservatives and Hungarian Orbanistas is natural.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.Unfortunately, instead of that natural affinity leading American conservatives and Hungarian conservatives to hone and sharpen each other through productive debate, it has simply led to American conservatives’ fawning over Hungarian policy and credulously accepting that whatever nice-sounding thing the government does must have a beneficial effect. Pappin recapitulates this mistake, which leads him to a consequential misunderstanding of what has actually happened in Hungary, and what it implies for conservative policy in the United States.

What Really Happened in 2010?

Here are the facts. Pappin dates the Hungarian turn in marriage, fertility, and abortion to 2010 or 2011. That’s true: Hungary’s demographic indicators all started to head in a direction conservatives like at around that time. Because 2010 is also when Orban’s party took office, conservatives leap to credit the change to Orban. But this is a strange way to interpret policy: merely taking office wouldn’t cause a change in marriage rates or birth rates. It’s not like Hungarian women said to themselves, “Well, Orban is in charge, I guess I won’t get this abortion now.” Likewise, Trump’s election didn’t cause a marriage-and-baby-boom. Actual policies cause changes, not just a new face at the top.

There were some important changes soon after Orban took office, like a new constitution with a lot of social-conservative-amenable language about the family, some legal changes cracking down on vagrancy, and also a law stripping many churches of their legal status. It was a mixed bag, early on.

Maybe a new constitution would cause Hungarians to suddenly feel extremely confident they’d get more support in the future, and so would lead to them getting married and having kids. Maybe. But there’s a more plausible explanation. Here’s Hungary’s fertility rate from 1985 to 2015, compared with the average of nearby formerly communist countries:

After the fall of communism, birth rates declined in virtually every formerly communist society to levels far below what women wanted. (Surveys show Hungarian women desire about two children each, on average.) Then, in most of those countries, birth rates started recovering in the early 2000s. But Hungary’s recovery stalled out in about 2005 or 2006. While the recovery from post-communist disorder was leading to families in other countries recovering missed fertility, Hungary began to decline again. What happened is straightforward: despite economic growth, Hungary’s unemployment rate rose steadily from 2000 to 2008, and then especially during the financial crisis. Hungary went from one of the lowest unemployment rates in eastern Europe in the early 2000s to above average in 2010. While social conservatives like to focus on Orban’s family policies, the actual force leading to his return to office in 2010—and fueling much of his ongoing popularity—was the promise of economic improvement. Indeed, in the first several years of his government, Orban slashed welfare benefits, imposed work requirements, and reduced the generosity of family spending, while presiding over a declining unemployment rate. Data from the OECD show that Hungary’s direct spending on children per child in Hungary has fallen persistently since 2010.

So you can’t really say that the family policies now associated with Hungary existed in 2010. They did not. What happened in 2010 was an economic turnaround, which is impressive, but isn’t really useful for making the argument for family policy. With a major economic turnaround (and a reduction in marriage disincentives baked into several welfare programs), marriage rates boomed, abortion rates fell, and birth rates rose. That’s an argument for competent economic management, not family policy.

With a major economic turnaround (and a reduction in marriage disincentives baked into several welfare programs), marriage rates boomed, abortion rates fell, and birth rates rose. That’s an argument for competent economic management, not family policy.

Did Hungary’s Family Policies Work?

Hungary’s distinctive family policy really began in 2015, with the CSOK program, which provided mortgage loan subsidies to families who had a certain number of kids. The way CSOK and many other programs worked was that the government offered families subsidized or forgivable loans for specific purposes if they had a certain number of children.

At first, CSOK was exclusively for new mortgages on newly constructed houses, and official government statements described it as a policy to replace decrepit old Soviet housing as much as a family policy. Later on, CSOK was expanded to remodeling projects and existing housing; as that expansion occurred, the government stopped talking so much about CSOK’s role in supporting the construction industry (political donors) or underwriting mortgage-issuing banks (political donors), and instead focused more on its role subsidizing family life.

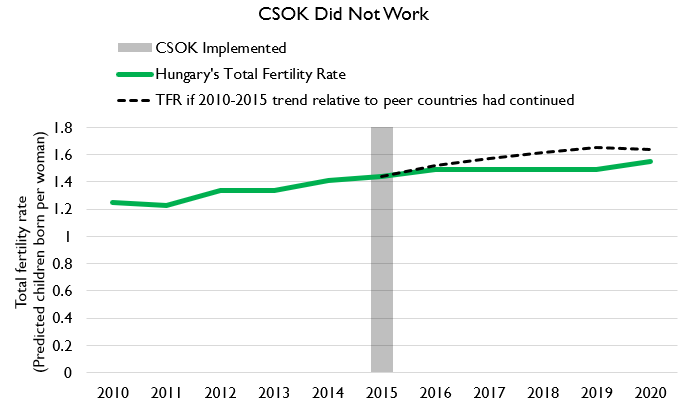

More programs followed, like loan subsidies for minivans (auto industry, political donor, check) or income tax exemptions for women who had large families (spoiler: there are very few women with more than three kids in Hungary who also work, so this generous exemption was generous to very few people). These programs all attracted suitable media attention, . . . but they basically failed to boost fertility. Here’s Hungary’s fertility rate from 2010 to 2020, with a comparison to what Hungary’s total fertility rate would have looked like if the 2010-2015 convergence with nearby countries’ fertility rates had continued:

Hungary’s birth rate was increasing. Then CSOK was implemented, and birth rates stopped rising. The program failed.

What Does Work: Cash

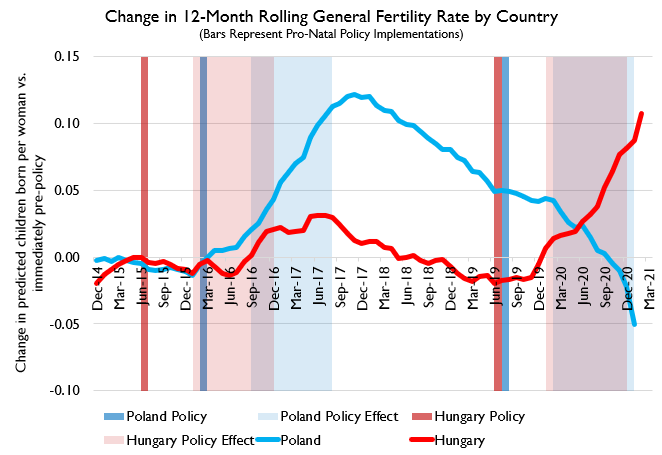

But you’ll notice an uptick in 2020. Here, there’s a real policy story. Hungary implemented a new program in 2019 in which married couples could apply for a consumer loan, to use on anything they wanted, with a portion of it being forgiven for each child they had within a certain time window. If they had three kids within nine years, the whole loan was forgiven. Births jumped upward almost exactly nine months after the policy was announced, as shown below in Figure 3.

Why did this latter program work when prior programs failed? One simple possibility is that the new program placed the least restrictions on use of funds. The money could be used for anything. It wasn’t a subsidy for a house or for a car. It was cash—a big lump sum of cash right up front: over $30,000 with no strings attached other than “have babies.” Adjusting for the fact that incomes in Hungary are a lot lower than in the United States, this would be equivalent to a $130,000 forgivable loan here. One can imagine that giving Americans $130,000 up front on the promise that if they have three kids within nine years they’ll never pay a dime of interest or principal would probably jumpstart babymaking here too! It’s a massive prepaid baby bonus! Giving people lots of cash right up front is the most effective way to boost fertility, so it’s no surprise this policy worked.

But this policy was also a repudiation, in many ways, of the distinctive policies of the previous five years. Instead of giving targeted loan subsidies for specific categories like houses or cars, the policy was effectively a direct cash transfer pre-paying for future childbearing. It’s a return to Hungary’s pre-Orban cash-based family support system. It has lower work requirements and wider eligibility than earlier programs too. To be eligible, one parent must have worked for at least half a year at some point in the prior three years. This work requirement is so low, it’s barely a work requirement at all.

A simpler way to do this than what Hungary has done would be to simply provide a baby bonus. There’s no need for all the much-publicized bells and whistles of Hungary’s policies. Indeed, Poland’s less flashy 500+ program, which simply provided a generous child allowance for families with two or more kids, yielded a bigger fertility increase than Hungary’s CSOK program. The figure below compares initial implementation of each program, and expansions of each program in recent years.

Hungary’s CSOK program only yielded a small baby bump, but Poland’s 500+ program pushed birth rates up by quite a lot. Over time, the effects of Poland’s 500+ program have faded, and the program’s expansion to first births in 2019 appears to have had no effect either, perhaps because few people make the decision to have a first child based on monetary concerns. Meanwhile, although CSOK did not help birth rates much, the more recent, and more cash-like, program appears to have boosted birth rates considerably. Indeed, Hungary’s birth rates have moved upward despite COVID-19 related headwinds, an impressive feat.

American conservatives can learn from Hungary: cash works, don’t get too creative, and try lots of stuff to see what works. To a considerable extent, all of this is Pappin’s actual point; he just mistakenly thinks Hungary is an exemplar of this approach. But the fact is that Hungary’s policy shift from 2010 to 2018 at least was away from simple cash benefits for families. Hungary’s case also shows that when jobs vanish, families suffer. We can’t just act like work disincentives, the national debt, or global supply chains can be wished away. Ensuring family policies do not lead to perverse economic outcomes is vitally important.

More broadly, conservatives should learn, but also critique: emulate what works, and oppose what doesn’t. What made Hungary’s family policy work wasn’t the populism, but the boring technocracy of it. Flashy populist programs failed, while just pushing cash out the door to families (as is the norm in countries like Sweden, Denmark, or Norway, all of which have higher birth rates than Hungary) worked. American conservatives should learn from this: if you want a higher birth rate, you’re going to have to pay for it.