Neoconservatives did not classify themselves. The name was assigned derisively by liberal socialists, who were looking for a snarky way to refer to once-liberal thinkers who “defected” to the other side. Some resisted the label. Others eventually decided to own it. Not many self-identify as neocons today.

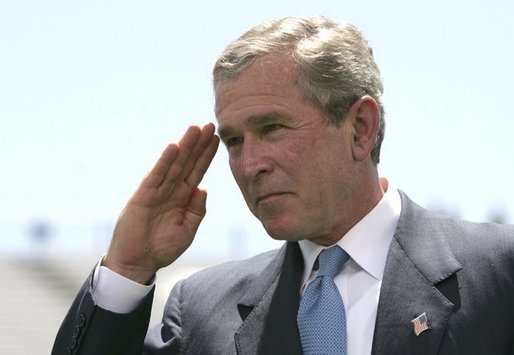

The neoconservative brand has been tarnished by the Iraq war and the simple passage of time. As the Cold War ended and crime fell, many planks of the old platform diminished in relevance. Neocons became the scapegoats for anything and everything that was wrong with George W. Bush’s administration. Many of the luminaries are still with us, but younger right-leaning intellectuals are often dismissive of neoconservativism. They want a new “neo.”

Under any name or none, though, neoconservatism needs a comeback. It’s time for young conservatives to move beyond the vague and illiberal fantasies of right-wing populism, applying themselves to a rebuilding of a more serious and grounded right-wing politics. Neoconservatives made some mistakes, as always happens in politics. Still, the movement provides a helpful template for those trying to navigate the road ahead.

An Enduring Template

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.There are many reasons why the time is ripe to look back on the neoconservative conversations of the ’70s and ’80s. Frightening geopolitical developments should motivate conservatives to reconsider the broad-brush indictments of “interventionism” that were briefly popular during Donald Trump’s campaign (which he himself quickly abandoned in office). Meanwhile, as the Republican Party trudges on through its tortuous efforts to generate a real policy agenda, we might think back appreciatively on previous decades in which neoconservatives served as the workhorses of conservative policy. Where have you gone, Irving Kristol?

On the cultural front as well, there is little wrong with America today that the neoconservatives didn’t anticipate. Our electoral map, even in Donald Trump’s America, still bears the marks of their deep influence. By blending trenchant social criticism with a pragmatic, can-do spirit, neocons were able to counter the left with a compelling political platform, expanding the Republican Party across the nation and turning the tide in the once-Democratic South. Neoconservatives had a sense of urgency about bolstering traditional morals and family structures against the rising tide of social chaos. At the same time, their disillusionment with Great Society reforms instilled a strong skepticism about top-down attempts at social engineering. Neoconservatives were interested in policy, but they also understood that policy has limits. The best-intentioned social programs inevitably precipitate some unintended consequences. That juxtaposition of productivity and skepticism gave the movement a distinctly conservative character, reflecting Edmund Burke’s exhortations to respect the value of prescription.

Skeptics will scoff, of course. Did Bush’s “Compassionate Conservatism” show a prudent aversion to social engineering? Was the War on Drugs modest in its use of government power? At what point shall we reopen the case files on Iraq?

All of these points merit attention, and indeed, now might be a good time to revisit old debates about the neoconservative platform. No doubt we’ll still identify many failures, but today, our evaluation of neoconservative successes and failures can take place against the backdrop of a decade of more populist right-wing politics. Has the fruit of this new era been sweet? Is it ripening?

When neoconservatives commanded a central place within the Republican Party, it had a substance and staying power that today’s legislators are obviously struggling to recreate. In the early Tea Party years, we spent much time discussing the sins of the neocons. Now might be a good time to ask ourselves: what did they do right? Could today’s conservatives do more to make the right into an attractive haven for a new round of disillusioned thinkers who feel “mugged” by the realities of the desiccated left?

The Resplendence of Truth

Part of the genius of neoconservatism lay in its willingness to champion what was hopeful and good in American life. The conservative stalwarts of the later twentieth century were not truly (as their detractors continually claimed) indifferent to the plight of the poor, but they were unwilling to hand over the future to the grasping fingers of envy and resentment. A nation addled by victim complexes cannot stay great for very long. The neoconservatives presented virtue and enterprise as a robust answer to the siren song of false compassion. That strategy could be applied to many different areas of American life. In the navel-gazing, Bohemian 1960s, neocons stepped forward to celebrate conventional bourgeois values. Against the spreading currents of libertinism, they unashamedly pronounced the enduring relevance of Judeo-Christian morals. In an era that seemed hypnotized by hedonism and vice, this celebration of health and discipline was attractive, even to Democrats like Daniel Patrick Moynihan, who worked tirelessly within his own party to stem the destructive flood of false pity.

Many influential conservatives of the late twentieth century had extensive experience wrangling with leftists. The term is most classically applied to those who defected from the left themselves, and many of their close allies (like William F. Buckley Jr.) had come of age as contrarian minorities on heavily left-leaning university campuses. Despite (or perhaps because of) that background, these conservatives assumed their countercultural posts with a kind of evangelical boldness, championing ideas and policies because they were good, not because they presumed widespread popularity and support. These earlier conservative writings show none of the demoralized bitterness that seems ever to be etched on the underside of the shiny populist coin.

In some ways, neoconservatism may have fallen victim to its own success. The early neocons, having come from the left, were eager to reform Great Society programs through hardheaded, data-driven pragmatism. They abhorred demagoguery and ideology-driven impracticality. Ironically, though, it may in some ways be easier to maintain those principles as part of a hated counterculture. As the neocons became mainstream within the GOP, they took on some of the characteristics the originators had abhorred. James Q Wilson may have been a committed empiricist, but the tough-on-crime campaigns of the mid-’90s made liberal use of demagoguery and cherry-picked statistics. The aversion to ideology wasn’t clearly in effect when we debated intervention in Iraq.

Recognizing this, we should be careful not to fall into nostalgic idolatry. Neoconservatives themselves were sometimes guilty of overreach, as political victories inspired a confidence that overshadowed their healthy skepticism. In any event, politics is an ever-changing beast; nothing goes back precisely the way it was. Changing circumstances demand updated platforms and policies.

Getting Back to Building

A neo-neoconservatism wouldn’t call for a re-invasion of Iraq, or a rash of new prisons. After Trump, unifying conservatives around a single platform will inevitably be a challenge, and North Korea, though terrifying, is unlikely to unite the political right in quite the way that the Soviet Union once did. Meanwhile, the erosion of traditional morals in the American mainstream may have pushed us to the point where it no longer makes sense to think in terms of “defining deviancy down” (as though progressives and conservatives were still fundamentally working within the same moral framework). Deviancy seems to have gone sideways in recent decades, and our rhetoric and political decisions need to be adjusted accordingly.

Might there still be value, though, in continuing the neoconservative conversation in its broader contours? Might there particularly be a value in younger conservatives applying themselves more seriously to this work of rebuilding? Young, right-leaning intellectuals are anxious to jump-start a new kind of conservative conversation, hopefully opening the way to a more unified coalition and a more cohesive policy agenda. These are worthy goals, but in their impatience to gain momentum, many are willing or even eager to jettison crucial elements of the conservative core. When we reach the point of bickering about whether to give up on traditional morals or free enterprise, it’s time to stop and backtrack. That’s not how conservatives think. And America still needs a conservative movement.

Drawing on the wisdom of the early neocons might help us to find a harder but ultimately more fruitful path. Instead of hunting down political heretics, work harder on cultivating common ground wherever you can find it. Don’t be above policy-making and institution-building, but do engage in these modestly, appreciating the natural limits of state action. Understand that health, prosperity, and goodness will always hold appeal across the political spectrum. Refuse to allow virtue to be hostage to vice.

To some eyes, neoconservatism seems a maze of contradictions. That may just reflect the complex balance of factors that enabled these ex-liberals to navigate the tightrope of politics for a surprisingly long time. The neocons saw Western civilization as a magnificent, but also fragile legacy. It has an unparalleled history of fostering human excellence, but it perpetually faces a host of threats, both from without and from within. Looking out from our present outpost, is anyone inclined to disagree?