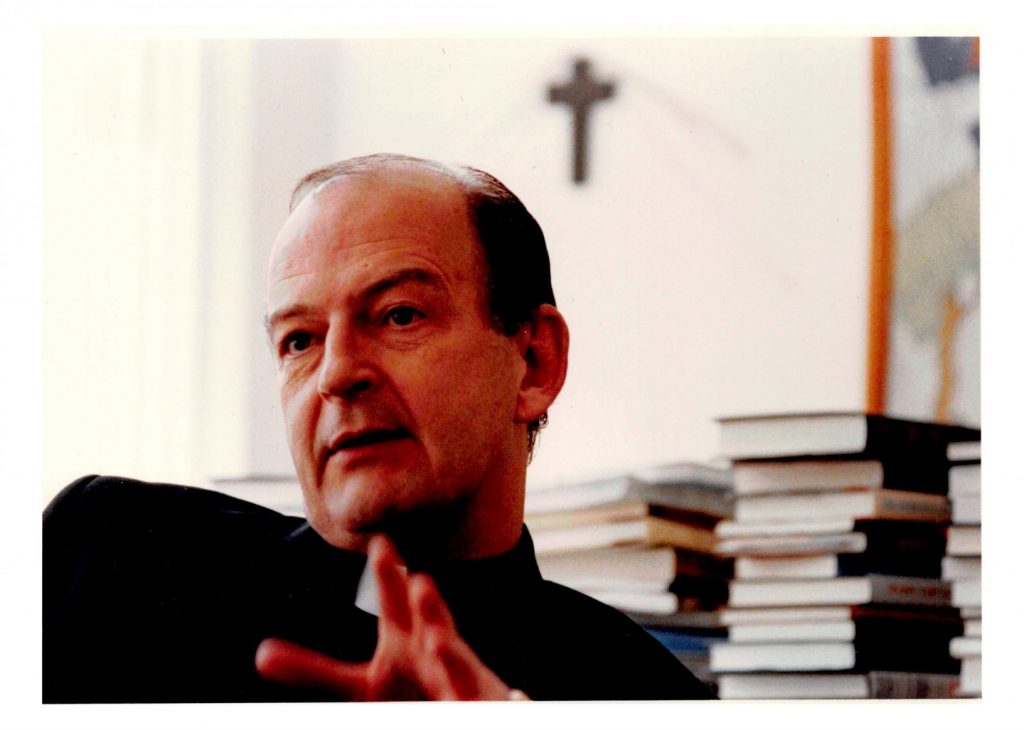

There’s no avoiding it: Fr. Richard John Neuhaus called himself a liberal. He did so with an undisguised hint of mischief, but his sincerity was genuine and unmistakable.

Richard’s life was marked by a series of conversions. Some were momentous, including his reception into the Catholic church. Some were subtle, including a slow movement away from Wolfhart Pannenberg as the major theological influence on his thought. Others were seemingly eschatological, including the announcement that he, a Canadian, would be meeting God as an American.

But one conversion never happened. His commitment to liberalism—to the liberal political tradition—was a striking continuity over four decades of public life. His persistence was remarkable, given its reception. How do I put this? Nobody entirely believed him. Not the secular left, for whom, according to a black legend, he was the clerical field general of an advancing army of Christian theocrats. Not the traditionalist right, for whom he was a kind of American Eusebius, offering the incense of popular piety to legitimize a new imperial order. And not even some of his friends, who joked that the label fit him no better than the youthful Mao shirt occasionally glimpsed in old photos.

Richard raised suspicions on all sides, then, and with an evident relish for the intellectual skirmishes that ensued. He aimed for attention, but not simply to provoke, and the fact that so many of his concerns remain our concerns only confirms how wisely he chose them and how successfully he sustained a public conversation about them. Debates about the meaning of “conservatism” or partisan labels held little interest for him, and he was serenely uninterested in academic fads or reputations. But about liberalism and its “falling flag,” as he put it, he cared deeply and wrote passionately.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.Richard was a both a leading participant in, and influential commentator on, a debate that has returned to public life with surprising urgency. I refer to discussions over Catholicism and liberalism, and their contested compatibilities. What Richard would think about the real-life satyricon of 2018 I cannot confidently say. But I’m certain he would have savored involvement in a debate that consumed him since the early ’80s. I’m confident, too, that he would have approved of the place of his magazine, First Things, in hosting its best arguments.

Richard never wrote a programmatic account of his understanding of liberalism. The treatise was not his genre, and I’m half-tempted to say the book wasn’t either. But across hundreds of essays, more than twenty books, and the world’s first blog—the Public Square—a consistent vision came into view.

It goes like this. Liberalism is a way of thinking about and engaging in the domain of life that we call the political. Its distinctive note is that it sees politics as a form of conversation. A liberal polity is a conversational polity: it comprises human beings bound together in argument, aspiring to order their common life through the exercise of persuasion, not the application of power. A liberal society is therefore a special kind of intentional community. It’s constituted by an agreement to participate in what the inaugural issue of First Things called “an engagement of our differences and disagreements about what is most importantly true.”

For Richard, the engagement of those differences pointed toward the inherently moral nature of public life. Moral deliberation, and the rival claims and hard controversies it inevitably involves, are not alien intrusions into liberal politics. They are a central component of its unabashedly moral enterprise. Richard wanted to save liberalism from a moral minimalism that paradoxically made it less tolerant and more conceited. The life of liberalism, he maintained, is simply the life of moral debate, fully and openly engaged, about how we ought to order our life together.

Richard didn’t arrive at this vision of liberalism through study. He was the best-read person I’ve ever met, but his political imagination wasn’t formed by reflection on intellectual history or the study of the American Founding. You might say his liberalism was empirical. He found it in observation and experience, rather than in books or university seminars. It reflected his involvement in the give-and-take of movement politics and coalition building that was his passion and special forte. But more importantly, it reflected the peculiar experiences, practices, and mores that he observed in American life.

Richard noticed a feature of democratic life that contemporary thinkers were inclined to ignore or malign. When Americans, in critical moments of self-affirmation or self-criticism, deliberate about our common life, we’ve historically done so in light of an acknowledgment of transcendent judgment over our nation. In making this observation, Richard meant to call attention to something deeper and higher than American civil religion. He meant that Americans have thought of their social bond as morally accountable to a reality beyond itself—as a compact among people under God, not a contract between autonomous individuals. With his friend Peter Berger, he therefore spoke of a “sacred canopy” that has enveloped popular understandings of national identity and purpose.

Richard was the first to acknowledge the fading power of this national self-understanding, as well as to warn against temptations to put it to ill use. As he conceded in his 1984 book, The Naked Public Square, the nation imagined by Winthrop, described by Tocqueville, summoned by Lincoln, and challenged by Martin Luther King had seen its sacred canopy fray and tear. Richard’s solution was forward-looking, not nostalgic, and sought to take into sober consideration the changing nature of the postwar consensus. It was to articulate what he grandly called a “public philosophy” for American life.

Now, Richard was not just a talker, but a talker who tended to dominate every conversation he entered, and it’s therefore unsurprising that his public philosophy was essentially a set of rules that prescribed how we ought to talk about political life. Its grammar proposed a set of interlocking moral truths whose common recognition, he argued, would sustain the challenge-and-response of liberal debate. They included the sovereignty of God, the sacredness of the person, and the role of government in protecting the human obligations and immunities that flow from them.

This public philosophy, whose details emerged in the back-page scuffles of his magazines, dictated little by way of public policy, but that was not its point. Its purpose was to carve out and defend what Richard called a “circle of civility” in a fragmented culture. Richard was responding to the shattering of a common moral language before contemporary philosophers were telling us how the cataclysm came about. His remedy was not to drain moral language of its significance, as his running feud with Richard Rorty showed. It was to demonstrate, as much through example as by argument, how certain first principles made civil debate possible at all. What John Paul II called the “subjectivity of society” reflected, for Richard, our continuing and often vehement political differences—not over the existence of moral truths, but over how we ought to live them out in the public square.

Liberalism is a protean term, and it’s fair to ask what vintage of liberalism this is—or whether it was the homebrew of Richard’s basement office on E. 19th Street. I think it could be described, with some imprecision, as a liberalism of means and not a liberalism about ends—a liberalism of the mean-time, as Richard might’ve said, and not a liberalism of meaning itself.

Neuhausian liberalism is the way we live out our lives in view of our shared creatureliness, fallenness, and, most importantly, in view of our confusions and differences about how to love and serve God in our time toward home. It’s a mode of political association that tolerates a range of disagreements about how best to fulfill our obligations to the truths we hold in common. I call this a liberalism of the mean-time because it’s a form of relativized, though not relativistic, politics. It recognizes the necessity of politics, but also affirms that it is neither the first nor last thing. Politics is a penultimate thing. Richard would probably say that this view offers the broadest tolerance possible and offers the surest ground of its practice. “We do not kill each other over our arguments about God,” he explained, “because it is God’s will that we do not kill each other over arguments about God’s will.”

But this liberalism depended on broad agreement about the basic shape and character of human life, on an anthropology that saw human beings as relational and responsible persons, rather than as self-fashioning individuals. Richard never argued that only Jews and Christians could be good liberals. But in arguing that the temporal power should be guided by religious truths, he came close. If liberalism depends on general agreement about our final end, as Richard thought it did, then dissenters cannot participate fully in its “circle of civility.” Richard admitted as much, insisting that liberalism must guard against what Newman called “false liberty of thought.” Richard had in mind secular doctrines that undermine liberalism’s root value, which is not the liberty of the individual, but its sacredness.

Richard had the heart of a theologian and the mind of a social critic, and little of him was devoted to pure philosophy. He was, however, advancing a philosophical argument, even if it went unelaborated. The argument, as I understand it, holds that there’s an intrinsic relationship between the knowledge of truth and the practice of tolerance. They are bound together for two reasons.

First, because only a genuine commitment to the truth makes tolerance possible. Assent to the truth must be done freely and with genuine understanding; it can be encouraged and rewarded, but it cannot be coerced. Tolerance for error is therefore not an endorsement of falsehood itself—for we do not, strictly speaking, tolerate what is false—it is a respect for the dignity of the knowing person, whom we do tolerate. Second, because tolerance is intelligible only with some presumed and shared understanding of the true and the good. After all, we do not tolerate what we think is true or good. We tolerate what we think is wrong or even bad—and, again, we do so out of a special respect for the truth and how it is known and loved by rational beings. I think this is how Richard understood liberalism philosophically, and why he thought its true enemy was not strongly held convictions about truth, but their absence or suppression.

With that seeming paradox, we are back to where a young Pastor Neuhaus was in 1975, surveying a confused nation in the year before its bicentennial and worrying about the unraveling of American liberalism after the civil rights movement. He published one of his most interesting books that year, Time Toward Home, which described an anxious America as the place of our earthly pilgrimage and the time of our testing. He was formulating phrases that he would return to almost verbatim in American Babylon, a book he would not live to see in print. There he described himself, just as he did three decades earlier, as “someone who tried to take seriously, and tried to encourage others to take seriously, the story of America within the story of the world.” Richard reasserted his belief that “God is not indifferent toward the American experiment” and that “we who are called to think about God and his ways through time dare not be indifferent to the American experience.” Toward America, Richard was many things. Always hopeful, occasionally childlike, sometimes angry, but never indifferent. Yes, America is Babylon, he wrote, but it is our Babylon. It’s the time and place God has given to us, our time toward home, and therefore a “time to think deeply and to think religiously about the story of America.”

This essay is adapted from a talk delivered on March 7, 2018 at the Catholic University of America, at a conference celebrating the life and letters of Richard John Neuhaus.