Fifty years ago Ralph Lerner, a University of Chicago political theorist and student of the American founding, published a fascinating article in the Supreme Court Review titled “The Supreme Court as Republican Schoolmaster.” There he took up a now forgotten practice that was common in the last decade of the eighteenth century—the first decade in which our country was governed by its new Constitution. Back then, justices of the Supreme Court spent a minority of their time each year in the nation’s capital, where they gathered together as the nation’s highest court, and more of it “riding circuit” and presiding over regional federal trial courts, where they came into regular contact with ordinary private citizens who served on juries, both grand and petit.

In this first decade of the new federal judiciary’s activity, justices in the circuit courts would often address a newly empaneled grand jury with what Lerner called a “political charge.” This amounted to a brief lecture to the jurors on the principles of our constitutional order, the rule of law, and the rights, duties, and virtues expected of the citizens of our republic. Done well (Lerner cites the examples of Chief Justices John Jay and Oliver Ellsworth), this hortatory exercise was both instructive and nonpartisan. Done poorly (he cites Justice Samuel Chase), it amounted to a partisan harangue of dubious propriety to a captive audience.

Since the political charge or exhortation was not directly relevant in a practical way to the work on which the grand jury was about to embark, the practice fell into disuse, then disrepute and oblivion. Perhaps it’s just as well. (Justice Chase was impeached and nearly removed in large part because of his abuse of the practice.) But Lerner’s article reminded students of the judiciary that while the practice lasted, it was an understandable effort on the part of learned public officials in a young constitutional republic. As Lerner put it: “Set apart from most citizens by temperament, education, acquired tastes, and responsibilities, the judges (at their best) could make the most of such opportunities as came their way to act as faithful sustainers and guardians of the regime.”

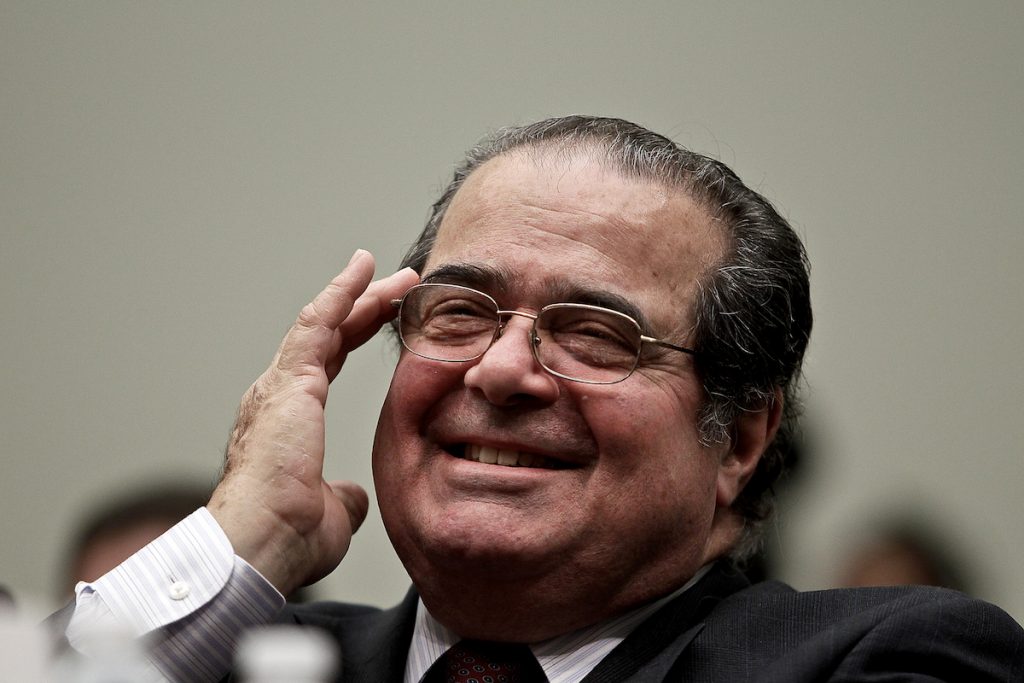

The late Justice Antonin Scalia appears to have taken his own opportunities to act as such a faithful sustainer and guardian of the American constitutional order in the many speaking engagements he accepted during his years of judicial service. In Scalia Speaks: Reflections on Law, Faith, and Life Well Lived, Christopher J. Scalia and Edward Whelan (one of the author’s sons and one of his law clerks) have judiciously collected four dozen examples of Scalia’s exhortations, arguments, and entertainments before almost every conceivable kind of audience.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.A Feast of Many Courses

Supreme Court justices do not merely vote on judgments in legal cases and announce them; they are expected to explain them to the parties involved and to the public. Hence every justice is obliged to be a writer on the job. Some write books as well—memoirs (Clarence Thomas, Sonia Sotomayor), histories (the late William Rehnquist), or works of legal scholarship (Stephen Breyer, Scalia himself). And surely invitations to give lectures and speeches in various venues pour into the justices’ incoming mail.

Antonin Scalia distinguished himself across the board. His judicial opinions are justly renowned for their clarity and eloquence; he was obviously the best writer on the Court since Robert H. Jackson, and many would say he was better than Jackson. Especially when writing not for the Court but only as himself in concurrence or dissent, Scalia could be funny, acerbic, angry, rigorous in logic, and devastating in his dissection of other opinions. As a legal scholar too, Scalia brilliantly expounded the traditional arts of textual interpretation in the law, in books such as A Matter of Interpretation and Reading Law (the latter co-authored with Bryan Garner), which will be read for decades to come.

But the speeches and lectures in this new collection are something else again. Scalia Speaks is a feast of many courses. Justice Scalia accepted invitations from universities and law schools at home and abroad, from civic organizations, high schools, Irish and Italian fraternal organizations, sporting societies, military chaplaincies, museums, historic sites, arts organizations, and religious institutions and societies. There are law lectures, commencement speeches, after-dinner talks, prayer-breakfast remarks, dedications, tributes, and eulogies. Every one of them is a polished gem of its particular genre, with wit, insight, and sentiment shaped exactly right for the audience and the occasion. On every page, we witness Scalia enjoying himself immensely and giving his listeners an unforgettable performance.

When legal professionals address amateurs there are certain risks, of course. The constraints on the judge are lifted, the scholar is not talking to fellow experts in his field, and all that immense learning can be employed in the most ponderous and plodding fashion. But not so here. Scalia knew how to move lightly through the legal materials he needed, making those materials accessible to untrained listeners while building a very pointed argument from them.

Arguing for Originalism

From various angles and in front of various audiences, we see Justice Scalia argue for originalism in constitutional interpretation—the view that the meaning of the constitutional text has been fixed from the start and must be discerned by the interpreter. The responsible judge is an originalist not because it imprisons the country in an inflexible legal cage built long ago by men long dead, but because it is the only method that protects the freedom of a self-governing republic of citizens from the usurpations of judges.

The only real alternative to originalism, Scalia argued, was some version of a “living Constitution” whose meaning is not fixed but varies from age to age. But the promises of the living Constitution are false; Scalia tells one audience that they may think “it will bring you flexibility and choice,” but in truth “it will bring you rigidity, which is precisely what it is designed for.” The judicial power to invalidate ordinary laws made by the people’s representatives, in the name of the people’s Constitution, is too momentous to be entrusted to the untrammeled will of judges. “If you believe in democracy,” Scalia says, “you are an originalist, because it is only the limitations that the people voted for—which means the limitations that the people understood they were imposing—that can frustrate the will of the people.”

Here we see Scalia the republican schoolmaster. Jurists like Jay and Ellsworth felt they needed to educate their fellow citizens in the norms, principles, and institutions of a new Constitution in its fragile beginnings, or it might not survive to maturity. More than two centuries on, Justice Scalia saw the Constitution as battered and abused by his fellow lawyers and judges, and clearly considered his public speaking opportunities to be both educational and restorative occasions. If his fellow citizens could understand the harm that modern judges had done, if they could understand why Supreme Court nominations now routinely generated political firestorms, if they could tell responsible judging from black-robed despotism—then perhaps Scalia’s beloved constitutional republic could right itself and endure for centuries more. And even if the hope of such restoration is forlorn, there is always inestimable value in speaking the truth.

A Combative Joie de Vivre

The love of truth pervades this book, and imparts to its author a combative joie de vivre that prevents even his harshest critiques from becoming jeremiads. One reason Scalia’s joy and even playfulness are so much in evidence is that away from his chambers and the work of particular cases, he is truly free to speak his mind. Substantive due process? “I do not believe in that doctrine.” The Miranda warnings the Court has required police to give to suspects for the last half century? There’s “no basis in historical practice” or the constitutional text for them. The similarly venerable protection given to the press when it libels public officials? That’s “assuredly not what the People adopted when they ratified the First Amendment.”

These judgments are not fully defended in the public speeches in this book, but they are confidently uttered and perfectly defensible. Some of them—not all—he elaborated in his judicial opinions. And the complicated relationship between his originalism and his respect for precedent is not something Scalia saw fit to explore in these informal public speeches. For that the reader would have to look to his opinions, articles, and books on the law. Here such peremptory judgments are meant to startle the listeners, to shake them from their complacent trust in the work of the Supreme Court.

But Scalia is not intent on detaching his listeners from trust in the Constitution itself, nor does he wish to make them cynical about their country or its history. Love of country and love of the Constitution—a simple and pure patriotism matched with a sophisticated historical sensibility—run through these speeches from end to end.

Scalia’s Sustaining Faith

Equally simple and equally sophisticated was Antonin Scalia’s Catholic faith, which is highlighted here in its own section of half a dozen speeches. His devotion to the faith can also be seen in his eulogies in the final section, as well as in the last public talk he gave (here titled “Natural Law”) in which he had the nerve to disagree with St. Thomas Aquinas in front of an audience of Dominicans. Scalia’s many critics have long claimed that his dissents from the Court’s invented “rights” to abortion and to same-sex marriage were proof that he could not disentangle his Catholic moral views from his legal reasoning. That argument cannot survive a fair reading of the speeches in this book—or of his opinions on the bench, for that matter.

But we can say that his faith sustained him, giving him hope, joy, good cheer, and the courage to keep writing and speaking on behalf of the rule of law, consistently and rigorously applied by judges. It also made him keenly aware of the vital role religion plays in shaping the character of citizens, and the character of the laws they make to govern themselves. Scalia was fond of quoting George Washington’s Farewell Address on this subject, and once took Washington as representative of the founders in general when he summarized their view this way: “the Founders believed morality was essential to the well-being of the Republic, and that religion was the best way to foster morality.”

Scalia knew it was worse than a fool’s errand—it was a fatal error—to chase religious faith from the public square. As just the sixth Catholic Supreme Court justice in history, he was the first whose own very public devotion to his faith put this conviction into action. This, along with his willingness to discuss the relationship of his religion to his official duties, made him a good republican schoolmaster to the last. Thanks to Christopher Scalia and Edward Whelan, his instruction will have a very long life.