For some time now, Rod Dreher has advanced the phrase “the Benedict Option” in First Things, his blog at The American Conservative, and elsewhere. Yet it has never been clear what choosing the Benedict Option actually entails. Some people take it to be a call to quietism or withdrawal from an irredeemable society, and thus propose more active options for Christian engagement. If they are right about what it is, the Benedict Option would be misguided. Dreher himself, in an earlier articulation of it, says it is the charge to be distinctly Christian and countercultural in the face of cultural hostility “even if that means some degree of intentional separation from the mainstream” (italics Dreher’s). But that already has a name: Christianity.

In his new book, The Benedict Option, Dreher makes it clear that the heart of the phrase is a feeling of alarm and alienation at no longer being at home in Western society, coupled with an intuition that traditional Christians have failed and need to change course. In his view, “Christian conservatives [can] no longer live business-as-usual lives in America . . . We would have to choose to make a decisive leap into a truly countercultural way of living Christianity, or we would doom our children and our children’s children to assimilation.” Christian conservatives have been “routed,” and the left “is pressing forward with a harsh, relentless occupation, one that is aided by the cluelessness of Christians who don’t understand what’s happening.” Dreher’s mission is “to wake up the church and to encourage it to act to strengthen itself, while there is still time.”

Dreher seeks to offer a critique of modern culture and to tell inspiring stories of creative countercultural Christians. His stories and spiritual counsel are on the whole sound and wise. Yet, his protests to the contrary notwithstanding, his book offers a standard decline-and-fall lament, taking readers from the glory of the High Middle Ages to moral and cultural decay in our own time. Propelled more by feelings than by slow, careful thought, this account is too swift and lopsided, lacking appreciation for the legitimate goods that have resulted from intellectual developments after the thirteenth century. Likewise, Dreher’s analysis of the right course for Christian political action suffers from a lack of clarity. A truly Benedictine account would correct both flaws.

Well-Trod Ground Trod Too Quickly

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.The phrase “the Benedict Option” is inspired by Alasdair MacIntyre’s 1981 study of contemporary moral discourse, After Virtue. MacIntyre ended After Virtue with a call to revive Aristotelian philosophy and communities of virtue. He offered a comparison between our own time and the decline of the Roman Empire in the fifth century, writing that a crucial turning point occurred when good people stopped trying to shore up Roman society and government and began building new communities in which moral life and civility could be sustained through the dark times ahead. We have reached that same point, MacIntyre continues, but the barbarians are not out in the wilderness; they run our universities and pass our laws. And we have not yet become conscious of this fact.

The solution, then, is to recognize our plight for what it is, and in the most famous lines of After Virtue, to begin

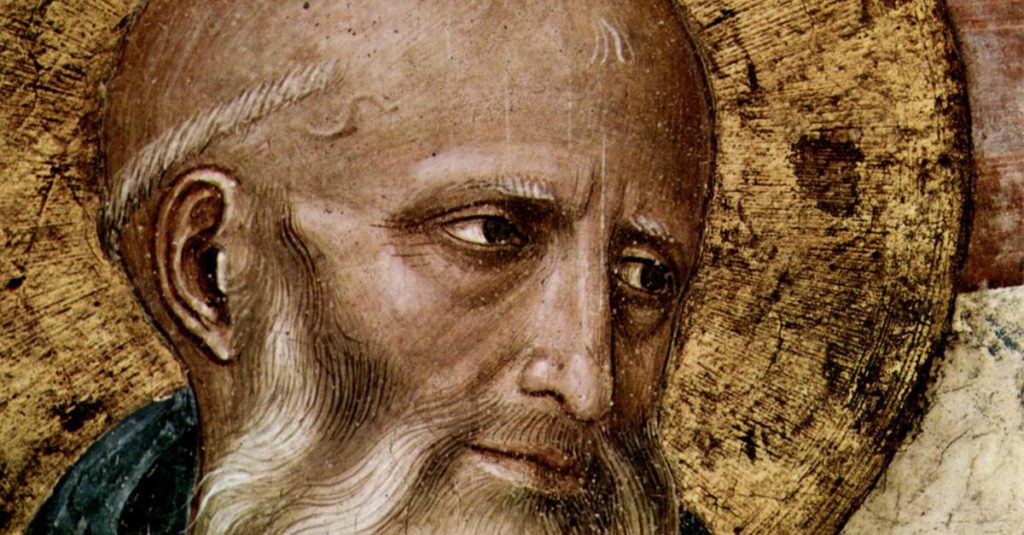

the construction of local forms of community within which civility and the intellectual and moral life can be sustained through the new dark ages which are already upon us. And if the tradition of the virtues was able to survive the horrors of the last dark ages, we are not entirely without grounds for hope. We are waiting not for a Godot, but for another—doubtless very different—St. Benedict.

The more American Christians began to feel like exiles in their own land, the more they gravitated toward MacIntyre’s image. Beginning with his 2006 book Crunchy Cons, Dreher began to use the phrase “the Benedict Option” to describe people who had begun living out their faith in countercultural, intentionally communal ways.

In The Benedict Option, the book, Dreher calls for a renewal of ascetic practices such as fasting for lay people, and urges his readers to see their work as a means of sanctification and not just acquisition. He wants Christians to see their homes as domestic monasteries, schools for the love of God and neighbor that keep the Sabbath and pray together. And he encourages them not to give their kids smart phones and to fast from technology at times themselves.

He also places a strong emphasis on education, urging parents to take their kids out of public or lukewarm religious schools. Instead, they should embrace classical curricula that teach Scripture and the Western tradition, in classical schools or in homeschooling. Dreher’s goal is the formation of communities that are countercultural without being totally closed off to the world or oppressive. He acknowledges that this will be a great challenge, but more details of successes and failures in this regard would have been welcome.

Dreher takes the American monks who refounded an abbey in Norcia, Benedict’s hometown, as an archetype of this way of life. The monks of Norcia believe that Christians should be as open to the world as possible without compromise. We should see the goodness in it and bring it out, not retreat behind defensive lines. This is the right stance for contemporary Christians to take, one advocated in Christian literature from the New Testament and the Letter to Diognetus down to authors such as Pope Benedict XVI in our own time. Unfortunately, Dreher is inconsistent in following this counsel.

This becomes apparent in his diagnoses of contemporary problems. With a helpful timeline by century, Dreher offers the now-standard historical genealogy of modernity. First there was the golden age of Aristotle, Aquinas, and philosophical realism in the thirteenth century. Nominalism brought all of this crashing down, creating a snowballing effect through the Renaissance and Enlightenment to today. To this general outline, Dreher adds Philip Rieff’s indictment of therapeutic culture and Christian Smith’s diagnosis of the Moral Therapeutic Deism that is replacing American Christianity.

All of this is well-trod ground. The problem is that Dreher treads too quickly and not carefully enough. He uncritically embraces the narrative that thinkers such as Patrick Deneen and Michael Hanby have advanced, without their nuance and without wrestling with—or even acknowledging—the legitimate criticisms of their arguments. He exhorts Christians to fight pornography, to support the unmarried—gay and straight—in their congregations, and to show young people the power and goodness of the Christian sexual ethic, which was powerfully different from the Roman ethic. But he does not flesh out the reasoning behind these exhortations. If young people are to understand why sexual complementarity is important, they will need to be offered a coherent vision with an argument, not a passing citation of Genesis. Similarly, establishing a link between birth control and transgenderism requires more than two sentences.

Christians in the Public Square

The book’s more serious weaknesses become apparent when Dreher attempts to analyze the role Christians should play in the public square. The heart of Dreher’s argument is that Christians have been complacently trusting that they would win political victories by voting Republican instead of building up their own religious communities and engaging broader cultural problems. As someone who spent two years working at First Things, one of the most politically engaged religious magazines, this critique doesn’t ring true to me.

Dreher repeats this claim throughout the book, but he never gives clear examples. He writes: “One reason the contemporary church is in so much trouble is that religious conservatives of the last generation mistakenly believed they could focus on politics and the culture would take care of itself.” Really? Were not conservative leaders such as James Dobson, Phyllis Schlafly, William F. Buckley, Jr., and Beverly LaHaye also cultural critics? And which religious leaders ever thought political power alone would bring about cultural renewal? Dreher writes, “Politics is no substitute for personal holiness.” Who ever said otherwise? What churches counseled their members to focus on votes but not on Bible study or community building? Dreher seems to view the excesses of some in the Religious Right and Moral Majority as representative of most believers.

Dreher also argues that Christians active in politics are naïve about their failure: “With a few exceptions, conservative Christian political activists are as ineffective as White Russian exiles, drinking tea from samovars in their Paris drawing rooms, plotting the restoration of the monarchy.” These activists fail to understand that “we failed.” So what should they do instead?

Here Dreher’s counsel for Christian political efforts is muddled. First, he writes, “Christian concern does not end with fighting abortion and with protecting religious liberty and the traditional family,” and he counsels conservatives to work with liberals on sex trafficking, poverty, and other issues with potential common ground.

But a few pages later, he writes that most American Christians do not realize the need to wake up and fight for their religious liberty: “The first goal of Benedict Option Christians in the world of conventional politics is to secure and expand the space within which we can be ourselves and build our own institutions.” Still later, he encourages Christians to take their cue from dissidents under communism and practice “antipolitical politics.” This entails unplugging from popular culture and creating “‘parallel structures’ in which the truth can be lived in community.”

Dreher’s example of a Christian leader who understands the Benedict Option is Lance Kinzer, a former Republican state representative from Kansas. After the defeat of Kansas’s attempt at passing a religious freedom law, Kinzer left state politics to focus on building up his local church and family. He also works for a public policy organization, traveling around the country advocating religious-liberty protections. By his own life Kinzer proves false the dichotomy between political activism and building up the church. Likewise, communist dissidents worked to create parallel structures and also founded movements like Solidarity to fight for democracy on a broader scale.

So which is it? Should conservative Christians engage in political activism on a wider variety of issues, or are they White Russian exiles who should disengage from political activism to build up the church in their communities, or should they disengage from most political activism except for issues of religious liberty? If the latter, how does that square with our obligation as citizens to combat the death of countless unborn children and promote the relief of the poor and the vulnerable? And how should conservative Christians expect to argue that their religious beliefs are worthy of protection without making public, political arguments for what they believe?

Not Benedictine Enough

Dreher has named his concept the Benedict Option after St. Benedict, but also after the “second Benedict,” Pope Benedict XVI. Ironically, the problem with The Benedict Option is that it is not Benedictine enough, as regards both Benedicts.

First, Benedictine thought is known for being slowly developed over time. Like Pope Benedict’s writing, it is deep and rich, eloquent without being rushed. These are qualities lacking in The Benedict Option, which feels more like a series of extended blog posts than a careful argument. Some ideas require book-length, not blog-length, thinking. Given the power of the emotions that propel them, proponents of the Benedict Option will need this kind of thinking in the years to come.

Second, Benedictine authors showed a great appreciation for the pagan authors of antiquity. In his magisterial study of monastic culture, The Love of Learning and the Desire for God, Jean Leclercq notes that St. Boniface taught that “the authors and the grammarians of antiquity must, then, be studied—but their works must be integrated into the life of the Church. What is not in conformity with Catholic tradition must be eliminated; what the latter has introduced into the expression of religious ideas must be added.” The Benedict Option lacks this careful appreciation and appropriation of thinkers after the Middle Ages. Christians have much to learn and be grateful for from this period. They should not view history as a total loss after Aquinas or the Reformers, or read Locke and Jefferson with less openness than they do pagan philosophers.

Third, Benedictines have hope. Indeed, Pope Benedict made hope a central theme of his papacy, especially through his encyclical on hope, Spe Salvi. Dreher does not exude hope. Thomas Aquinas identifies despair and presumption as contrasting sins against hope. In his effort to combat presumption, Dreher too often succumbs to despair. For example, he writes: “There are people alive today who may live to see the effective death of Christianity within our civilization.” Throughout history, Christian cultural dominance inevitably waxes and wanes, as does Christian institutional strength. But despite the many challenges facing twenty-first century Christians, there are significant pockets of health in American Christianity. Even if our churches shrink, the network of flourishing parishes, lay movements, and religious orders shows no signs of being wiped out.

Fourth, Benedictines were grammarians. They cared deeply about words and their meanings and usage. Instead of calling Leah Libresco Sargeant an “effervescent Benedict Option social entrepreneur” they would recognize her for what she is: a Christian with a gift for hospitality and community-building. Sargeant notes that this kind of hospitality is not new, and neither is the Benedict Option:

People are like, ‘This Benedict Option thing, it’s just being Christian, right?’ And I’m like, “Yes! You’ve figured out the koan!” But people won’t do it unless you call it something different. It’s just the church being what the church is supposed to be, but if you give it a name, that makes people care.

She’s right about what is best about the Benedict Option—it’s just Christianity. But she’s wrong about the effect of the name. The Benedict Option is not a mystery designed to break open the mind; it’s a catchphrase that expresses a feeling of alarm and an intuited need for redirection. If the Benedict Option is just Christianity, it is neither inherently Benedictine nor is it optional. If it is a feeling and intuition, it needs to be guided by careful, prudent thought so that it bears good fruit. Dreher describes the question facing today’s Christians as “not whether to quit politics entirely, but how to exercise political power prudently, especially in an unstable political culture.” But that has always been the question facing Christians—and it is one to which Dreher never offers a clear answer.

These reservations aside, many readers will find Dreher’s counsel on practical spiritual matters helpful, even as they wish for clarity in his argument. Living the Christian faith intently in communities has been the heart—and challenge—of Christianity from the beginning. For like the monastic life, the Christian life has one ultimate goal: quaerere Deum—to seek God.