I imagine the decent statesman to be constantly frustrated. Hoping to make his country more peaceful and just, he finds himself equipped with tools like marginal tax rates and prolix regulations. And even when the mechanisms of government work as they ought to do, the people, culture, and market are stubborn. Forget the good intentions of statesmen; the good actions of statesmen are often just fruitless.

But occasionally, a crisis gives the statesman power to settle matters of life and death. Free to determine the heart of his polity’s moral character, the decent statesman must long for the frustrations of normal times.

The leaders of the Jewish state find themselves in such a position today. Hamas has kidnapped about two hundred Israelis. Some of the hostages were reportedly killed in Israeli strikes aimed at their captors in Gaza, and Hamas is likely to keep its militants and weapons near whichever captives are still alive. The terrible upshot is that the war against Hamas may implicate the Jewish state in the deaths of the world’s most vulnerable Jews.

It will be excruciating for Israeli officers to order attacks that might harm the very people the Israeli military exists to protect. The Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) may not be able to surprise important targets without incidentally condemning Israelis to death. And if Hamas credibly offers to exchange hostages for its militants now in Israeli custody, it may be difficult for Israel to refuse. These grievous options are nevertheless Israel’s least egregious means for executing the first duty of any sovereign, which is to keep its citizens safe from violence.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.Exchanging hostages for militants isn’t new to Israel. In 1985, in 2000, and most famously, in 2011, Israel swapped hundreds of imprisoned terrorists for a small number of captive Israeli soldiers. In the most recent trade, Hamas released a single Israeli corporal, Gilad Shalit, in return for more than one thousand militants, many of whom were serving life terms in Israeli prisons.

Israel’s willingness to trade hundreds of its enemies for a few of its own has often been praised as a species of moral and national excellence. The appeal isn’t hard to see–whatever the released militants might do tomorrow, today Israel gets some of its people to safety. The Jewish tradition highly values the redemption of hostages and sympathizes profusely with their predicament, as Mikhael Manekin correctly noted in The New York Times.

But securing the freedom of the captured is neither an ethical nor a Jewish absolute. The Shalit trade, in particular, should now be recognized as a barely mitigated disaster. A government dedicated to keeping Jews safe set loose a small army of men dedicated to getting Jews killed. One of them, Yahya Sinwar, is the current chief of Hamas. It is likely that many others among the released prisoners were somehow responsible for the horrors of October 7. To rescue a single famous and deserving Israeli, Israel’s government endangered numerous and no less deserving Israelis whose names nobody knew. Recent events indicate the degree to which Israel’s enemies now believe that taking Jews hostage strengthens rather than weakens the position from which they menace the Jewish state.

A trade now would be even worse. The released militants—and it would be many, given the great number of Israeli hostages—would replenish the ranks of a deadly adversary that Israel finally has the national will and the international support to eliminate. Since its 1988 charter, Hamas has been assiduously committed to the destruction of the Jewish state. Hamas will be eliminated by force or not at all. Graves and Israeli prisons–those are the only safe places for its militants.

The Jewish tradition combines great compassion toward hostages themselves with great prudence about rescuing them. The Babylonian Talmud records the worry that paying kidnappers excessively encourages them, thus endangering Jews still at liberty—very different from Manekin’s endorsement of “sacrificing everything to return the captured.” Now, the Gaza hostages were not taken just for monetary ransom—they were kidnapped by murderers. The Jewish tradition understands hostages to be generally at risk of death, and it also commands doing anything except idolatry, certain sexual sins, and bloodshed to rescue people in danger. Rabbi Shlomo Goren, the first chief rabbi of the IDF, was impressed that the notoriously grievous condition of Jewish hostages did not prompt the great medieval and early modern rabbis to endorse an unconditional duty to get captives back. Goren argued that it was illicit to endanger Jews generally to bring home individual Jewish prisoners.

Goren’s point is that the Jewish community neglects its duty to protect its citizens when it complies with efforts to imperil those citizens. His worries are highly relevant now. Trading terrorists for hostages would not only encourage Hamas to take more captives; it would supply Hamas with the essential means to do it. Manekin writes that “Israel will not want to allow a prisoner release to be seen as a victory for Hamas,” but the danger is not optic—any prisoner swap to which Hamas consents will amount to a victory for the group, whoever handles the public relations.

Israel’s obligations to its citizens still at liberty broaden its military options, because failure to strike militants holding hostages in Gaza means endangering civilians in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem. The judgments to be made here are vague and imperfect, but so long as the IDF doesn’t know hostages are going to die in a strike, a strike will often be the best way for Israel to execute its obligations to all Israelis.

Women and children might be a special case. The gruesome degradations to which Palestinian terrorists subject Jewish women are not new. They go back to Jerusalem’s Nebi Musa riots of 1920, which were incited by Haj-Amin al-Husseini, the most important Palestinian nationalist until Palestine Liberation Organization chief Yasir Arafat. The parading of bloodied Israeli women around Gaza City—to popular jeering—embodies the horror of Israel’s enemies. An Israeli government official denied a Reuters report that Qatar is mediating a possible exchange of female Palestinian militants in Israeli custody for the women and children recently kidnapped by Hamas. But an exchange limited to female prisoners might be worth doing, since they are as a class much less dangerous to Israelis than their male counterparts.

Israel is no doubt already trying to rescue hostages in Gaza, though the IDF has other tasks besides. Israel’s leaders have determined that Israelis will not be secure so long as Hamas survives. But destroying the group means endangering hostages, because strikes against militants might kill captive Israelis.

Israel can’t resolve its difficulty just by respecting its duties as a sovereign fighting in an area with civilians. The laws of war generally accepted by Western countries permit bombing a building holding civilians if civilian harm isn’t the purpose of the bombing, and if the military gain of the bombing isn’t disproportionate to the harm to civilians. But if the civilians are Israeli, the IDF seems bound to a higher standard. Governments are supposed to keep their citizens from violent harm, not just to refrain from harming their citizens on purpose. The safety of Israeli hostages is not just one important consideration among many: it is intrinsic to the aim of Israel’s just war against Hamas.

Certain otherwise permissible tactics seem to be absolutely incompatible with Israel’s duties to Israeli hostages. Imagine that Hamas militants are holding Israeli hostages in one of the group’s many tunnels under Gaza City. Filling up the tunnels with concrete might, under other circumstances, be a good way to kill Hamas militants while protecting Israeli soldiers. But a filled-up tunnel asphyxiates anyone inside, whether hostage or militant. Israel will have failed in the most basic way to keep its citizens from harm.

Even so, Israel has quite a bit of room for action. In particular, the IDF does Israeli hostages no injustice if it exposes them to danger while trying to free them, i.e., while trying to kill their captors. Imagine a building filled with hostages and terrorists that would be virtually impossible to take with ground troops but could be partially demolished with explosives, giving hostages some chance of escaping. Such a bombing is comparable to a highly risky surgery: no bombing means the hostages will stay in Hamas custody and probably die, while a bombing allows the hostages some possibility of eventual safety.

Israel’s obligations to its citizens still at liberty broaden its military options, because failure to strike militants holding hostages in Gaza means endangering civilians in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem. The judgments to be made here are vague and imperfect, but so long as the IDF doesn’t know hostages are going to die in a strike, a strike will often be the best way for Israel to execute its obligations to all Israelis.

Painful days are ahead, as the IDF fights to free all Israelis from Hamas’s depravity. Whatever its particular tactics, Israel’s best hostage strategy is to hunt down every single member of Hamas, and to warn everyone considering a career in anti-Jewish terrorism of the deadly professional hazards.

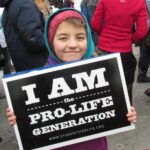

Image by “Michael” and licensed via Adobe Stock. Image resized.