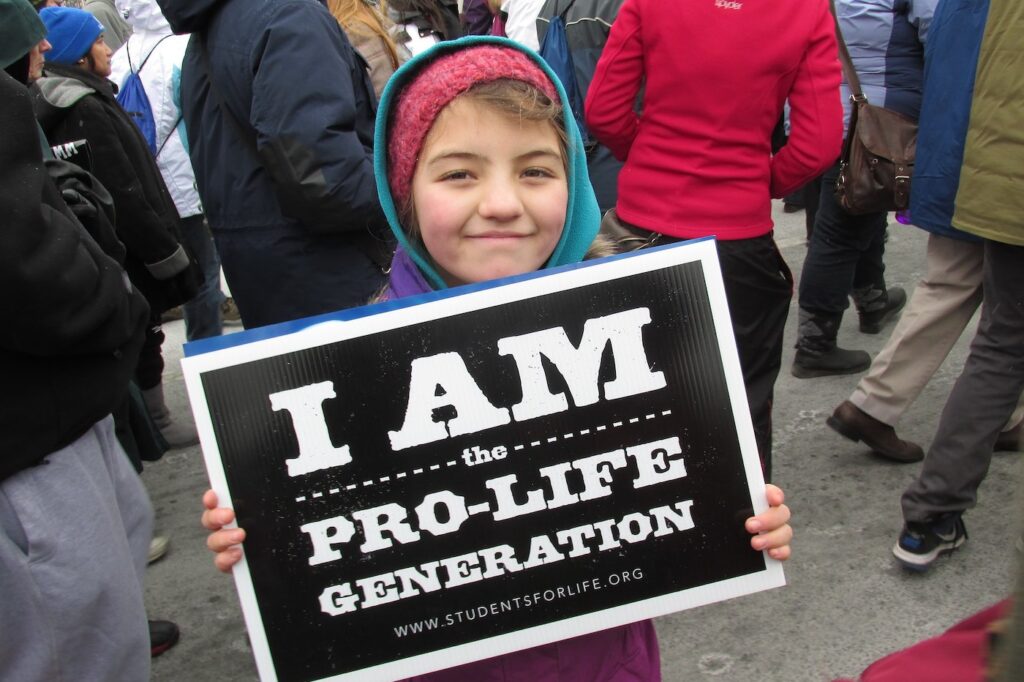

Last week, for the first time in its history, the March for Life took place in a post–Roe v. Wade country. Celebration was in the air, to be sure, and rightly so. But there was also a strong undercurrent of uncertainty, as the movement looks to a future full of new challenges and thorny strategic questions. While in years past marchers would chant, “Hey hey, ho ho, Roe v. Wade has got to go,” this year’s march featured slogans like, “We are the post-Roe generation, and we will abolish abortion.”

The unspoken question hovered in the air: how, exactly, are we supposed to do that? This question has consumed the pro-life movement since the Supreme Court handed down its Dobbs decision last summer. Though the movement had decades to prepare for this moment, it’s little surprise that a master plan has yet to appear. In previous decades, pro-lifers rarely saw eye-to-eye on strategy or rhetoric, but they had temporary reprieve from charting the way to an abortion-free future because they coalesced around the most necessary project: bringing about the end of Roe, so that the people and their elected representatives can protect unborn children from abortion.

Now that Roe is finally gone, that clarity of purpose has dried up with the last of the celebratory champagne. There’s been talk for decades about making abortion illegal and unthinkable, but far less explored is the notion that we might coordinate a strategy for doing so. Plenty of people have lots of ideas for what comes next, and a select few have grand plans, but there is no secret roadmap coordinating the next phase of the fight against abortion. Instead, it is becoming clear that this will be a battle fought in stages, requiring both cultural and political tactics such as improved messaging, state- and community-level support for women, electoral and ballot campaigns, and federal and state policymaking.

In this context, some in the movement have suggested that a national march isn’t as important as it once was, that pro-lifers should focus their firepower at the local level, where intense policy fights are playing out. But the national March for Life is as important as ever, especially in the absence of clear federal policy objectives and in the midst of disagreement among Republican leaders as to their responsibility on the issue.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.Despite these debates, there’s opportunity to build consensus around a national strategy. Some on the right argue otherwise, but it seems clear that both Dobbs and the Fourteenth Amendment leave room for Congress to protect unborn children from abortion at the national level, if only to set a ceiling above which no state abortion law can go. The fact that states can now act in defense of human life doesn’t absolve the federal government of its duty to do the same.

In the wake of Dobbs, a significant number of ostensibly pro-life politicians have declared that they consider abortion a states-only issue, despite having voted in the past for federal regulations on abortion. Meanwhile, others on the right argue that being vocally pro-life has cost the GOP too much politically. A national demonstration like the March reminds these politicians that pro-life voters don’t intend to take the Dobbs victory as an opportunity to pack up and go home. Pro-lifers should push for change at the state level, too, and the March for Life has begun helping them do so, planning annual marches in capital cities across the country. But if pro-life Americans wish to remain an influential interest group at the national level, they would be wise not to send the message that federal politicians can brush abortion policy aside indefinitely as a matter for state lawmakers to sort out.

Likewise, a continued insistence on national policymaking will set the tone for future elections and for any candidate who would claim to be pro-life and expect the movement’s support. In the wake of last November’s midterms, commentators on both left and right asserted that American support for legal abortion was a decisive factor in Republican underperformance. But as I wrote in an essay here at Public Discourse, this argument ignores significant data showing that Americans want to protect unborn children throughout most of pregnancy. It also ignores that a significant number of vocally pro-life Republicans won by enormous margins, which makes little sense if we are to believe that the midterms demonstrated anti-Dobbs backlash.

A national demonstration like the March reminds politicians that pro-life voters don’t intend to take the Dobbs victory as an opportunity to pack up and go home.

In short, the claim that opposition to abortion cost Republicans in the midterms, a claim that Donald Trump repeated wrathfully earlier this month, demonstrates an unsophisticated grasp of the intricacies of the 2022 midterms and of the broader abortion debate. The problem isn’t the GOP’s position; it’s the GOP’s failure to message effectively on the issue. It is the Democratic Party, not the GOP, that holds the most extreme, most unpopular position on abortion.

Democrats support taxpayer-funded abortion for any reason through all nine months of pregnancy, along with proposals to eliminate every state law regulating abortion even slightly. The Republican platform supports protecting all unborn children from the moment of conception, but unlike Democrats, most GOP politicians are willing to back interim policies more in line with public opinion, such as a ban on abortion after 15 weeks. If the median voter has yet to recognize this reality and vote accordingly, the problem is not with the GOP’s reasonable pro-life stance; it is with Republican candidates who won’t articulate their position out of fear that voters will punish them for being pro-life.

They would be smart to fear the opposite. In a recent press call, Marjorie Dannenfelser—president of influential pro-life action group Susan B. Anthony Pro-Life America—vowed that any 2024 Republican contender who won’t back federal limitations on abortion would have “disqualified him or herself as a presidential candidate in our eyes.” Presumably, the group will maintain a similar attitude toward any candidate for national office, presidential or otherwise—and that threat should be enough to get the attention of any GOP hopeful.

Some Republican politicians appear to have internalized the belief that the pro-life movement is the world’s cheapest date, an interest group easily satisfied with an annual failed vote to defund Planned Parenthood and the occasional comment about how Roe was wrongly decided.

Politicians at the national level should be prepared to offer vocal support for specific pro-life policy agendas, no matter what office they seek. Presidential candidates should be expected to voice support for federal abortion limitations and promise to lobby Congress on their behalf. They should also support all possible pro-life goals that fall within the scope of their constitutional role. This could include removing funding for abortion businesses through executive agencies; enforcing conscience protections for pro-life doctors, employers, and insurers; and reversing the Biden administration’s relaxation of safety regulations for dangerous chemical-abortion pills.

Pro-life congressional candidates, meanwhile, should promise to end government subsidy of abortion businesses, strengthen conscience protections, and protect unborn children and infants through existing legislation such as the Born-Alive Abortion Survivors Protection Act, the Pain-Capable Unborn Child Protection Act, and a federal form of a heartbeat bill. Even if it would serve only as a teaching and messaging bill for now, they should introduce legislation to abolish abortion. Pro-life candidates should be prepared to exercise rigorous oversight of executive agencies under a pro-abortion administration, and in a congressional minority they should attempt to block any legislation that includes abortion funding or that attempts to codify Roe.

Some Republican politicians appear to have internalized the belief that the pro-life movement is the world’s cheapest date, an interest group easily satisfied with an annual failed vote to defund Planned Parenthood and the occasional comment about how Roe was wrongly decided. Up until now, thanks to Roe, calling oneself a pro-life politician hasn’t required much at all. This is the moment for pro-lifers to prove those tepid leaders wrong and insist that any candidate who calls himself pro-life must do more than gesture vaguely to state lawmakers. As the March for Life demonstrated, pro-life Americans still have momentum. They would be wise not to give it up.