This essay is part of Public Discourse’s Who’s Who series, which introduces and critically engages with important thinkers who are often referenced in political and cultural debates, but whose ideas might not be widely known or understood. The series previously considered the life and work of Hannah Arendt, Antonio Gramsci, Jacques Maritain, Michael Oakeshott, Charles De Koninck, and Harry V. Jaffa and Allan Bloom.

Every year I teach a class on the collapse of Christianity in western society, asking the question why it was so easy to believe in God in the year 1500 and yet so difficult today. And in helping students to answer that question, my most useful guide has been Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor. Indeed, the question itself is drawn from one of his major works, A Secular Age.

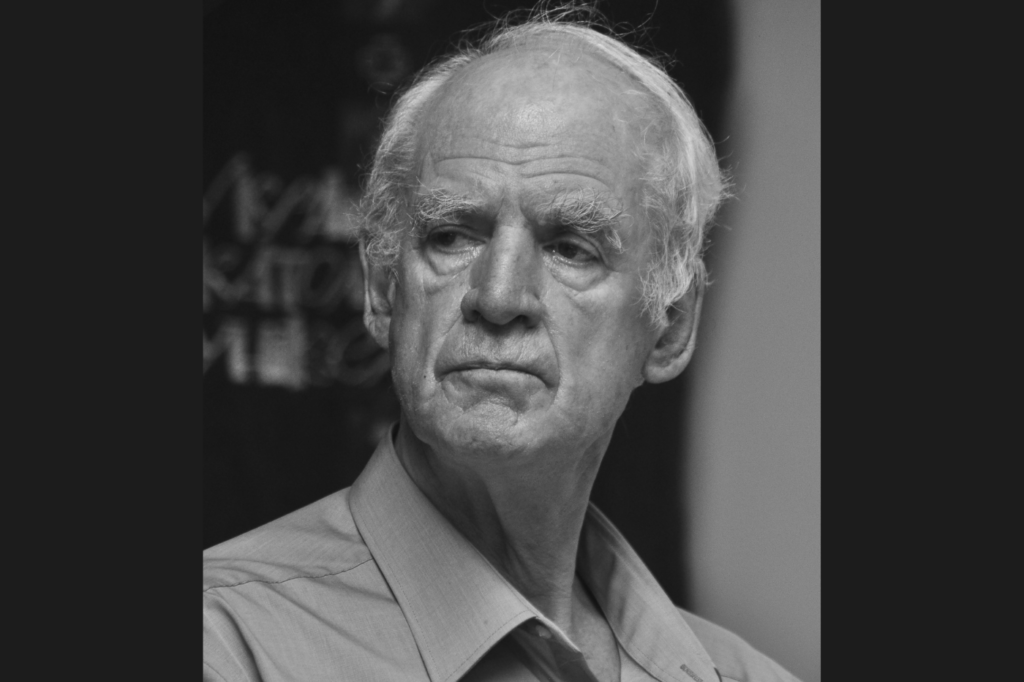

Taylor is a remarkable philosopher. He has made significant contributions to studies of Hegel, the importance of language, and the nature of politics. He has also developed theories of selfhood, of which Sources of the Self and its successor, A Secular Age, form a stunning tour de force. In addition, Taylor has also been active politically, helping to found New Left Review and standing for election in Canada as a candidate of the New Democratic Party on three separate occasions. Even though he’s a man of the left, those of a more conservative bent have much to learn from him.

Given the wide-ranging nature of Taylor’s philosophical interests, an introductory essay such as this must be highly selective. Yet there is a theme that ties Taylor’s work together, from Hegel to his interest in language: philosophical anthropology. This subject investigates the question: what is it that makes human beings and their social existence distinctive? This question is central to his arguments in Sources of the Self and A Secular Age as he investigates how individuals imagine themselves.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.The Failure of the Popular Narrative

Perhaps the most common explanation of religious decline in western society is that religious belief is now obsolete thanks to the growth of scientific knowledge. This account views religion as a means of control over nature that, in the wake of scientific and technological developments, has lost its importance. Thus, where once the farmer prayed for rain, now we have irrigation. Where once the villager at the foot of the volcano engaged in sacred rites to placate the volcano god, now we understand that seismology, not animal sacrifice, is a better predictor of eruption. Sometimes this is called the subtraction narrative: it accounts for the modern world by seeing it as what is left after religion has been removed or replaced by science.

This is in many ways the classic Enlightenment account of secularization, found variously in Kant’s notion of enlightenment as humanity reaching adulthood, Freud’s critique of religion as infantile, and Darwin’s proclamation of evolution. Taylor’s concern, however, is that it is too simplistic an account for it never asks a very important question: why does science come to have such authority that it is able to displace religion? The point is profound. Most people in the West do not believe in the authority of science because they are deeply read in scientific matters. Rather, they live in a world where science is intuitively plausible, just as five hundred years ago people lived in a world where religion was intuitively plausible. The question of the replacement of the latter with the former cannot therefore be answered simply with reference to science. The question of how and why science has been granted such authority is the real issue, and one that the standard narrative assumes rather than explains.

Where once the villager at the foot of the volcano engaged in sacred rites to placate the volcano god, now understand that seismology, not animal sacrifice, is a better predictor of eruption.

The Social Imaginary

In light of this, Taylor points to what he calls the social imaginary. The phrase is somewhat inelegant, using the adjective “imaginary” as a noun. Yet the concept is important. The social imaginary is the set of beliefs and practices that reflect and reinforce the intuitions of a given culture or society. Saluting the flag, celebrating July Fourth as a holiday, and believing in the wisdom embodied in the U.S. Constitution would be three examples of things that have traditionally informed the American social imaginary. Few people ask why they do or believe these things; they are simply intuitive to those who belong to the culture of the United States and provide the framework or the lens through which the nation and its relationship to its citizens and to other nations are understood. Families too have their ritual, rhythms, and assumptions that inform how their members understand themselves and relate to others.

Thus, for Taylor, the question of how religion moves from being the default intuition of the members of a society to being optional or even marginal is a question of how the social imaginary has been transformed. The shift to scientific supremacy is a matter of the imagination, not of the blunt facts of science intruding upon us.

The Disenchantment of the World

Central to this transformation is what Taylor (borrowing from Max Weber) calls disenchantment. While the medieval world was enchanted, the modern world in which we dwell is disenchanted. A naïve response to this might be that our world too is full of interest in the supernatural—not simply in terms of traditional religious commitments, where church, synagogue, temple, and mosque continue to find a place in the lives of many people—but also in the plethora of other spiritualities, from yoga to tarot cards. Do these things not prove that we still live in an enchanted age?

Such an objection carries some weight with those who wish to read “disenchanted” as connoting the wholesale rejection of religion or mystery, but it does not really address what Taylor is pointing to. A disenchanted age is not necessarily characterized by complete repudiation of the supernatural. Rather, it is characterized by a fundamental shift in the function of the supernatural. And a world where we now have a choice of enchantments, so to speak, is a world that is differently enchanted—and arguably disenchanted—because the supernatural no longer stands in the same relation to the world as it once did.

A couple of examples help clarify Taylor’s point. Take a traditional Catholic who believes in the ecumenical creeds. In so doing, he believes the same thing that Christians committed to those creeds have believed throughout the centuries. But there is a difference: today’s Catholic cannot believe them in the same way as, say, a Catholic in 1500. This is because today’s Catholic chooses to believe them, and that in the face of a cultural default that does not do so. The Catholic in 1500 really had no choice and, in believing, reflected the cultural intuitions and dispositions of his day. On this level, such faith represents something different today.

A disenchanted age is not necessarily characterized by complete repudiation of the supernatural. Rather, it is characterized by a fundamental shift in the function of the supernatural.

As a second example, imagine being a Christian believer in 1500 and waking up one morning to find that one does not believe in God any more. Everything fundamentally changes at that point. Up until then, you believed that the only thing keeping the universe in order, the only thing that guaranteed that the sun would rise each morning, was the existence of God. To cease believing in him is therefore virtually impossible and, if done, requires a fundamental rethinking of everything.

Today, doubt among religious believers and even complete loss of faith are rarely accompanied by a deep existential crisis about the entire universe, even if they precipitate a certain localized angst about relationships or personal mortality. This is because even religious believers are accustomed to living in a world that seems to operate effectively for believer and unbeliever alike. For example, experience teaches that antibiotics are a more reliable form of medical treatment than prayer alone. One can, of course, see antibiotics as a gift of God and an answer to prayer, but one does not need to do so. Nor does their efficacy depend on that belief. Our world is thus at least much less enchanted than that of 1500, even if individual groups maintain certain supernatural beliefs.

The Buffered Self

At the heart of this disenchantment for Taylor is not the traditional science-versus-religion narrative we noted at the start. Rather, he sees the key as being a transformation in the way in which the self is understood. By self he understands not merely the awareness individuals might have of themselves as individual self-consciousnesses. For Taylor, selfhood is how people understand themselves as individuals in connection to the world around them, and what they see as the nature of being a human person. The contrast between the Middle Ages and today is one that Taylor characterizes as between the porous self and the buffered self.

The porous self is one that does not draw a sharp boundary between the inner and the outer, between the psychological and the material, between the physical world and the spiritual. The buffered self is the self that does make a clear distinction between these things. And it is the rise of the latter that connects to the disenchantment of our current age.

The distinction is important but also complex. Indeed, both Sources of the Self and A Secular Age spend significant time exploring the distinction, and any summary runs the risk of oversimplification. Nonetheless, a couple of examples can again illuminate Taylor’s argument.

One example he uses himself is that of depression. In medieval times, depression—or melancholy as it was called—was connected to the notion of black bile. Today, we connect it to physiological issues such as a hormonal imbalance. One might be tempted to say that the difference between the two is thus simply one of depth of scientific knowledge: we now know that black bile does not exist, but both medievals and moderns see that a physiological cause for psychological dysfunction is in play. But this would be to misunderstand the difference between the two. While we moderns see hormonal imbalance as causing depression, the medieval mind sees black bile as being itself the melancholy. In other words, we distinguish the self—a psychological entity—from the physical, which acts on the real “us” as an external force; the medieval sees the self as in the grip of the physical and inseparable from it or, better still, permeable by it.

The physical world carried a powerful authority that extended to the spiritual and determined the nature of the self. But we moderns do not live in such a world. Ours is a world of immanence, not transcendence, explicable in terms of itself and where the supernatural does not plausibly blend with the natural.

A second example is that of the relationship between the supernatural and the natural world. For the medieval mind, the spiritual or supernatural boundary was a physical presence in the natural world: religious relics possessed an intrinsic power, for instance. Thus, when the king touched the one suffering from scrofula, the power of the physical touch healed the illness because the king, by virtue of his status as king, possessed supernatural healing powers. Likewise, when a fragment of the true cross was adored, the pilgrim was blessed. On the negative side, goblins, demons, and even the devil himself were physical realities within the material word. The physical world carried a powerful authority that extended to the spiritual and determined the nature of the self. But we moderns do not live in such a world. Ours is a world of immanence, not transcendence, explicable in terms of itself and where the supernatural does not plausibly blend with the natural. Even Christians who may well believe in a personal devil will typically not imagine him as a discrete physical presence in a particular place, but rather as a supernatural influence that cannot be specifically localized.

The displacement of the porous self with the buffered self is a long story, but with the crisis of the papacy in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, and with the Reformation of the sixteenth, the nature and stability of external authority started to become more and more equivocal. Add to this changes in technology, above all the printing press (with the correlative rise in literacy and then private reading), and economies (with the move from dependence on the land and the seasons to production and trade).

These changes meant the old external framework for identity and a sense of self started to weaken and then plunge into constant flux. The material world became less authoritative. The result was that there was an inward move, so that identity and security came to be found more in the individual psychological sphere than in the given external world. Montaigne gave a literary focus to the first person as Descartes did the same from a philosophical perspective.

The exploration of the inner space became critical. And as this happened, so the porous self gave way to the buffered self. Such a self will tilt toward finding science, for example, an increasingly plausible way of understanding the universe, not because it understands the elaborate arguments, but because the scientific way of looking at the world—as material that in itself possesses no intrinsic spiritual significance—resonates with the intuitions of the buffered self. The really important things for the individual are psychological. The material world is a separate sphere.

There is far more to Taylor’s philosophical analysis of modernity than can ever be covered in the space of this article. But above all is the central key to his thinking: to understand our world, we need to understand how human beings intuitively relate to that world. That requires understanding the changes in the notion of selfhood that have taken place over the last five hundred years. Only then will we come to a better understanding of why religion and religious people find themselves in such a highly contested position in our culture.

Image credit: Makhanets – Own work. Previously published here.