This essay is part of Public Discourse’s Who’s Who series, which introduces and critically engages with important thinkers who are often referenced in political and cultural debates, but whose ideas might not be widely known or understood.

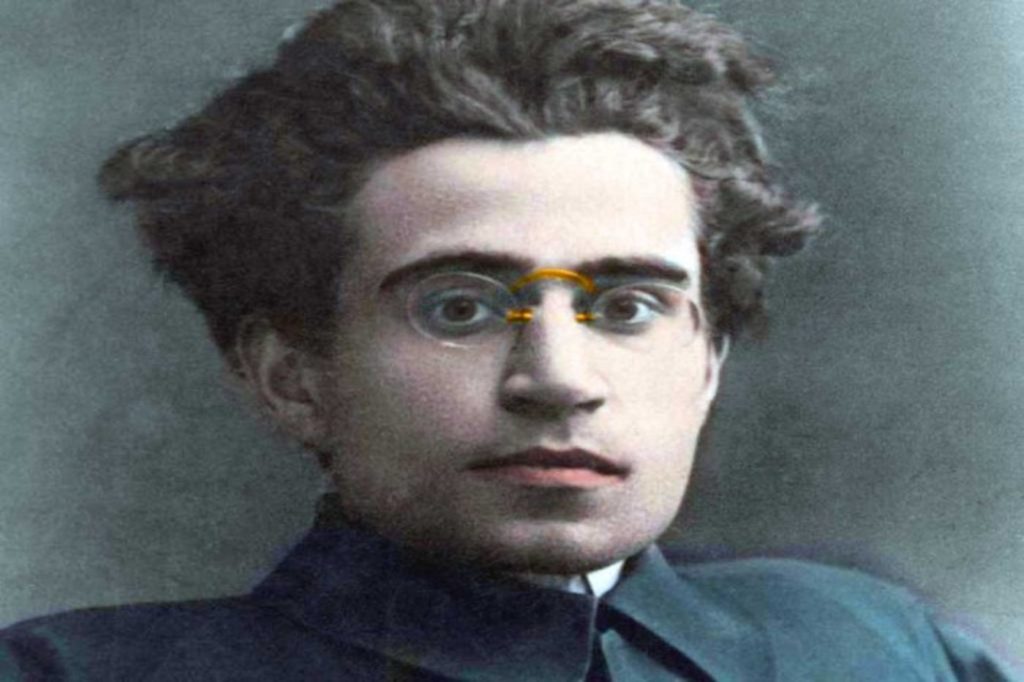

Antonio Gramsci, Italian philosopher, writer, socialist, and politician, was imprisoned by the fascist government of Benito Mussolini in 1926. Despite serious ill health, his incarceration permitted him to write a series of Prison Notebooks that would radically reshape the Marxist mindset of many theorists and activists. Indeed, his death—which occurred one week after his release from jail—conferred on him the status of a martyr, whose spirit would be invoked throughout the socialist salons of Europe, and across the universities and educational institutions of the West. In Gramsci, the intellectuals had found a socialist saint who absolved Marxism of its Stalinist sins, and who charted the way toward a slow but steady revolution, the outcome of which would be to seize and dominate the so-called “bourgeois” bastions of culture, education, and politics.

Today, the Gramscian revolution has succeeded where most rival movements have failed. Existentialism, structuralism, and postmodernism have come and gone, but Gramsci’s ideas have become entrenched dogma throughout Western academia and society. For example, Critical Race Theory, so-called “woke” culture, and the dominance throughout the liberal arts of studies that seek to deconstruct supposedly deep-rooted patriarchal structures all testify to what author and academic John Fonte once described as Gramsci’s “long reach.”

The impact of Gramsci’s vision is also evident in politics, most notably in America and Europe, in the form of policies intended to reorder society in line with radical liberal orthodoxy. This includes the undermining of the traditional family, the rush to drive religion to the margins, and the “canceling” of those who question this extreme agenda.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.Controlling the Culture

There are two key reasons for Gramsci’s emergence as the high priest of the new cultural order. First, he eschewed scientific or deterministic Marxism, which emphasizes material forces, in favor of a more humanistic approach, which emphasizes ideas and identity. Second, he emphasized the importance of the intellectual in the service of the revolution.

On the first point, if traditional Marxism considered the socioeconomic “base” as the driving force of history, Gramsci insisted that the cultural and ideological “superstructure” is equally important. For him, the forward march of history toward its socialist denouement can only be achieved when the proletariat not only assumes control of the material “means of production,” but also those forces of “cultural production,” such as the arts, education, the media, and the organs of knowledge, that a society uses to perpetuate itself.

This adapted version of Marxism recognized that humans do not acquire identity solely through their engagement with the material world. As Hegel understood, there are equally significant “spiritual” or immaterial aspects of our condition that form the basis of self-understanding. It is true that Gramsci followed Marx in rejecting Hegel’s idealistic theory of self-identity as “false consciousness.” For them, the spiritual aspect of Hegel’s dialectic was the epitome of “bourgeois alienation.” However, if Marx rejected it outright, Gramsci saw that identity and selfhood are as much the product of what he termed “ideology” as they are of economic factors. Therefore, he realized, you could not change a society without changing how it perceives itself, and how it thinks of itself.

Gramsci realized that you could not change a society without changing how it perceives itself, and how it thinks of itself.

This explains the second reason for Gramsci’s influence—his view of the significance of the intellectual. By “intellectual” he did not mean someone exclusively engaged in abstract theoretical speculation, but one who “exercises organizational functions in the broad sense, both in the field of production, and in the cultural one, and in the politico-administrative one.” In this view, each social group acquires an identity based on the functions of those who, in various ways, reinforce that identity. Behind the priest, for example, is an administrative network that includes not only clerical functionaries, but theologians and scholars who, through ideas, give the Church, its ministers, and lay faithful a “homogeneity and an awareness of its own function.” Without the intellectual, institutions would be devoid of ideological unity and identity.

Consequently, if society is to take a successful socialist turn, the “new organic intellectual” must be given a privileged position. For it is only those who dominate the cultural and academic sphere who can undertake the crucial labor of critiquing the prevailing structures of society and steadily changing its ideological self-image.

Ideological Hegemony

Gramsci believed that the socialist revolution was not solely against capitalism as an economic system, but was equally opposed to what he described as the “ideological hegemony” of the capitalist class structure. In contrast once again to classical Marxism, he suggested that even more powerful than the military-industrial structures that sustained a system were the ideological means of exploitation by the dominant class to retain power. For Gramsci, hegemony is both brought about and sustained by the subtle manipulation of the “popular consensus” in any given society. This is achieved by the intellectual class through that society’s educational, religious, cultural, and civic institutions.

Thus the realm of what Hegel called “consciousness” (Geist) is of crucial importance, for it is not merely an outgrowth of the underlying economic and material factors at play but is equally powerful in driving social change. Hence, what the revolution requires is an infiltration by organic intellectuals of the media, the Church, the academy, and the cultural sphere, to “demystify” what the bourgeois class structure has “legitimated” as reality. In doing so, it must provide an alternative to the prevailing ideological hegemony. This, however, could not be achieved in the short-term because of the deeply entrenched nature of advanced capitalism and its hegemonic control of civil society. Rather, the battleground must be in the arena of ideas and culture where popular consensus is formed. This would be a long war, the aim of which would be what Gramsci termed “counter-hegemonic consciousness transformation.”

Where classical Marxism had predicted that capitalism would collapse of necessity, Gramsci insisted that the birth of a true socialist order could only be accomplished through human action. Historical change happens not because it is driven by underlying deterministic forces, but because human actors alter or transform the consciousness, or ideology, of a particular age. However, the weapons of organic intellectuals are not military but cultural, meaning that they are engaged in a culture war aimed at countering the hegemony of bourgeois civilization.

This war must be fought not at a global but at a national level, for there can be no predetermined template whereby specific cultural traits can be transformed. What the intellectual must do is forge a culture war against the popular consensus of particular contexts. In this way, Gramsci’s cultural revolution takes aim at each national culture and seeks to change it accordingly. As stated earlier, it does so by undermining the hegemonic control of cultural, academic, religious, and political institutions by the “bourgeois” order in any given place. In turn, this will necessitate a knowledge of the local cultural norms so that they can be demystified in light of revolutionary alternatives.

Gramsci’s Legacy

The appeal of Gramsci—over and above such fellow-travelers as the French Marxist philosopher Louis Althusser—is not only that he rejected mechanistic Marxism and its revolutionary excesses, but that he also perceived some redeeming features in bourgeois culture. One of the principal purposes of taking each national culture on its own terms is that it will reveal the ways in which that culture has opposed injustice and inhumanity. The fact that such social protest emerged within the context of bourgeois culture does not, in his view, delegitimize it.

For Gramsci, the weapons of intellectuals are not military but cultural, meaning that they are engaged in a culture war aimed at countering the hegemony of bourgeois civilization.

Hence a genuine national-popular cultural revolution will endeavor to tap into already existing modes of social protest, whether in the arts, in the academy, or in trade unions or solidarity movements. Being local and cultural, the Gramscian revolution is opposed to the traditional Marxist insistence on a revolutionary struggle that is global, historically determined, and oblivious to the importance of ideology and consciousness in the pursuit of countering hegemonic control.

It may be too much to say that Gramsci rehumanized Marxism, as if such a thing were possible. Perhaps, however, his greatest achievement—despite his anti-Hegelian posturing—was in showing why consciousness (or Geist) is the central feature not only of change, but of human experience itself. In contrast to Marx, he understood the Hegelian notion that changes in the material world are predicated on changes in consciousness. In other words, ideas matter, and (as Hegel rightly understood) as our concepts change so does our reality. Put simply, the Gramscian intellectual agrees with Hegel that, as Gramsci himself phrased it, man “is above all else—mind.” However, unlike Hegel, his goal is to use ideas as a means of subverting one “ideology” for another. On this model, “counter-hegemonic consciousness transformation” is not a process that leads from alienation to self-identity. Rather, it is one that seeks to alienate people from the cultural, moral, and political legacy that is their own.

Where Hegel sought to bring the reader from estrangement to full self-awareness, Gramsci and his apostles condemned Hegelian self-satisfaction as “bourgeois” smugness. If Hegel believed that we could only be at home in the world by seriously engaging with the spiritual legacy of art, religion, and philosophy, Gramsci believed that this ought to be subverted except, of course, for those little pockets of socialist resistance that can be found on its margins. Where Hegel offers reconciliation to reality, Gramsci makes a virtue of estrangement by rejecting “the best that has been thought and said” in favor of emancipating alternatives. In so doing, he denies belonging and identity for a form of spiritual homelessness that renders people “strangers to themselves.” This, however, does not result in “liberation” from hegemonic control, but instead severs people from the sole means they have of acquiring genuine self-knowledge.

The prevailing dominance of so-called “cultural Marxism” throughout the institutions of Western civilization shows that Gramsci succeeded where many fellow Marxists abjectly failed. Their insistence on a material revolution devoid of spiritual content led to short-term political gain, but nothing more. Gramsci, on the other hand, inspired a revolution that has radically transformed the cultural and political landscape. Even the most casual observer of changes in the academy to its curriculum, and the Western canon on which it was originally founded, cannot fail to see the impact of Gramsci’s “long struggle” of the intellectuals and their war waged against our cultural legacy. Even those who have never heard his name can clearly see the consequences for art, literature, and politics of a revolution that aimed at ideology over truth.

Where once our academic institutions were founded on the principles of Cardinal John Henry Newman’s The Idea of a University, today many of them disregard the pursuit of scholarship and truth for politically charged courses rooted in woke ideology. Those traditionally-minded academics who protest are likely to lose their jobs. Likewise, the art world is now dominated by those who consider themselves the vanguard of social justice. No longer is art a revelation of the sacred form of life, or a manifestation of the higher ideals to which we humans can aspire. Rather, according to one convocation of American museums, the purpose of the contemporary museum is to reconcile “with communities for past injustices,” with “decolonization” and “social justice” as guiding principles.

Gramsci may have died a broken man without any obvious legacy. However, the fact that he is now regarded as a martyr-saint to an entire generation proves not only that he rose from the ashes of his prison cell to become the most influential Marxist writer of the twentieth century, but that he successfully sowed the seeds of revolution in the heartland of the enemy. That those seeds have finally come to fruition suggests that Antonio Gramsci’s long struggle is finally over, and that his legacy, however regrettable, is secure.