speaking one evening to a large meeting of pastors and organizers, when he received news that his home had been bombed while his wife and daughter were inside. With the condition of his family uncertain, Dr. King informed the congregation of the attack, urged them to go home directly, and exhorted them to maintain nonviolence. He raced home to find dozens of black citizens surrounding his house. When attempts by police to disperse the crowd raised tensions, King, flanked by the segregationist mayor, police chief, and police commissioner, told the crowd, “Love our enemies … Love them and let them know you love them … Go home and don’t worry.”

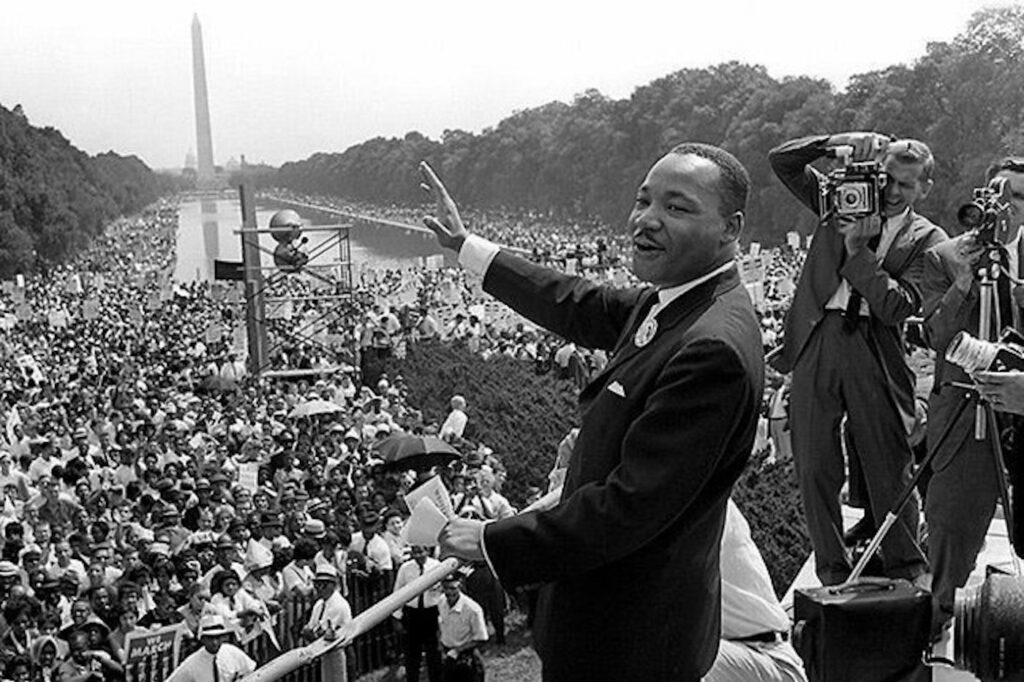

Other attacks against King in which he refused to retaliate—or advised such restraint in others—are well-documented. Indeed, these examples became a policy of non-violence. Before protests and marches, King and his colleagues in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) conducted training sessions in non-violence for all participants.

It was rooted in King’s Christian philosophy and his adoption of Jesus Christ’s injunction to “turn … the other cheek.” In other words, refuse to retaliate when you’re the target of violence, insult, or hate. Cornel West and Robert George wrote some years ago,

King was truly radical in his literal reading of Jesus’ command that we love others unconditionally, selflessly, and self-sacrificially. And by “others,” he meant everyone—even those who defend injustice. He believed in struggling hard, and with conviction, for what one believes is right; but he equally insisted on seeing others as precious brothers and sisters, even if one judges them to be gravely in error.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.

“Turning your cheek” was one way which Christ taught to treat one’s adversaries. He also told his disciples to “Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you.” Christ enjoined those assaulted, spit upon, or cursed to bless rather than retaliate; the Apostle Peter, later wrote: “Do not repay evil with evil or insult with insult. On the contrary, repay evil with blessing … ” The ethic has a foundation in the third book of the Torah, Leviticus: “Do not seek revenge or bear a grudge against anyone among your people but love your neighbor as yourself.”

There will be plenty of opportunities to turn the cheek in the years ahead. Pregnancy resource centers have been burned and vandalized. Large, shouting, defamatory crowds have protested outside some Supreme Court Justices’ homes since May 2022. Congressman Mike Johnson’s Resolution, introduced at the start of the 118th Congress, recorded that abortion activists “have defaced, vandalized, and caused destruction to over 100 pro-life facilities, groups, and churches” since the leak of the Dobbs opinion last May. FBI Director Christopher Wray testified before a Senate Homeland Security Hearing last November, “Since the Dobbs decision, probably in the neighborhood of 70 percent of our abortion-related violence cases or threats cases are cases of violence or threats against … pro-life organizations.”

The Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision last June returned abortion to the democratic process, shifting responsibility from the Court to voters and elected officials. Pro-life organizations have espoused a “culture of life” in America for decades. But why is it especially important to embrace King’s commitment to non-violence and peace now?

Shaping Public Sentiment

Abortion has moved from the Court to “public sentiment,” in Abraham Lincoln’s phrase. “[I]n a government like ours, public sentiment is everything, determining what laws and decisions can and cannot be enforced.” He recognized as well its practical constraint: “Our government,” Lincoln said, “rests in public opinion. Whoever can change public opinion, can change the Government practically just so much.”

While legal reform is important, what might shape public opinion most in coming years is a cultural ethic that eschews contempt, hate, retaliation, or violence. These attitudes and actions are incompatible with respect for human beings and their dignity. Instead, patience, restraint, forbearance, and resilience are necessary virtues. This is precisely why King’s example is so instructive: his radical commitment to loving every single human being—even those who attacked his own family—inspired many to rethink their views on race.

King’s non-violent ethic implicates more than “tone”; it is driven and informed by a generous desire to persuade rather than denounce adversaries. Besides non-retaliation, advocates should also demonstrate verbal self-restraint: instead of hate or abuse, advocates need to patiently listen, be thoughtful and give reasons for their convictions. Questions may be more effective than denunciation.

The strength of humility—a balanced understanding of one’s status—undergirds this cultural ethic. Humility marks the most memorable speeches and actions of some of America’s most influential leaders. George Washington resigned his military commission in December 1783. At the end of his First Inaugural, Lincoln sought to draw Americans to consider common ground and “the better angels of our nature.” In his Second, he urged Americans to persevere in the work “with malice toward none, with charity for all.” As David Bobb has written, humility helped Frederick Douglass “reach many who otherwise might not have listened to the message of equality and liberty for all.”

Humility and restraint do not mean failing to express one’s convictions. Rather, these virtues are preconditions for more powerful and persuasive expression of one’s convictions. In his sixth debate with Senator Stephen Douglas in 1858, Lincoln acknowledged that there were differences of opinion on the slavery question but, to his mind, the “difference of opinion, reduced to its lowest terms, is no other than the difference between the men who think slavery a wrong and those who do not think it wrong. The Republican Party think it wrong—we think it a moral, a social and a political wrong.”

Indeed, advocates must remain clear about the moral stakes of abortion. But the non-violent ethic of life will reinforce the witness of conscience that drives objections to killing innocent human beings. By refusing to retaliate with violence or hateful rhetoric, advocates for life will enhance their moral witness.

Lasting Reform

Beyond attitude and rhetoric, what are some of the practical actions that a non-violent ethic of life would embrace? One of the most impressive expressions of this cultural ethic is the vast outreach of direct services for women—delivered today by 2700+ privately-funded pregnancy resource centers across the nation—that have grown since the 1960s. These work to counter the conditions—including abandonment, pressure, and coercion—that often lead to abortion.

A robust discussion is already underway about various policy proposals, such as elevating the role of fathers, reinforcing marriage as society’s cornerstone institution, scaling back no-fault divorce laws, flexible work and family leave policies for employees, and policies that encourage men to take greater responsibility for their children and the mother of their children.

But the reception and effectiveness of any policy reforms may well be enhanced by a capacious culture of life grounded in respect for the dignity of all people that King modeled so well.

Though such practices will seem fantastic to many, there are historical examples of their success. Besides King and the SCLC, the non-violent resistance of Poland’s Solidarity, the witness of the co-founders of Voice of the Martyrs Richard and Sabina Wurmbrand imprisoned in Romania during the 1950s and 1960s, the example of Nelson Mandela after his release from prison, and the campaign by William Wilberforce against slavery in the British Empire—all these non-violent movements yielded significant social, political, or cultural reforms.

It’s difficult to precisely forecast the influence of an ethic of persistent charity, and whether this ethic will impact the most hostile or hard-hearted. However, it might inspire greater trust in spectators and bystanders. It might win over those who aren’t totally sure what they think of abortion but are watching advocates’ moral consistency and the respect they show their adversaries. After the bombing of her home, Coretta King wrote that one cop said to another, “If it hadn’t been for that … preacher, we’d all be dead.”