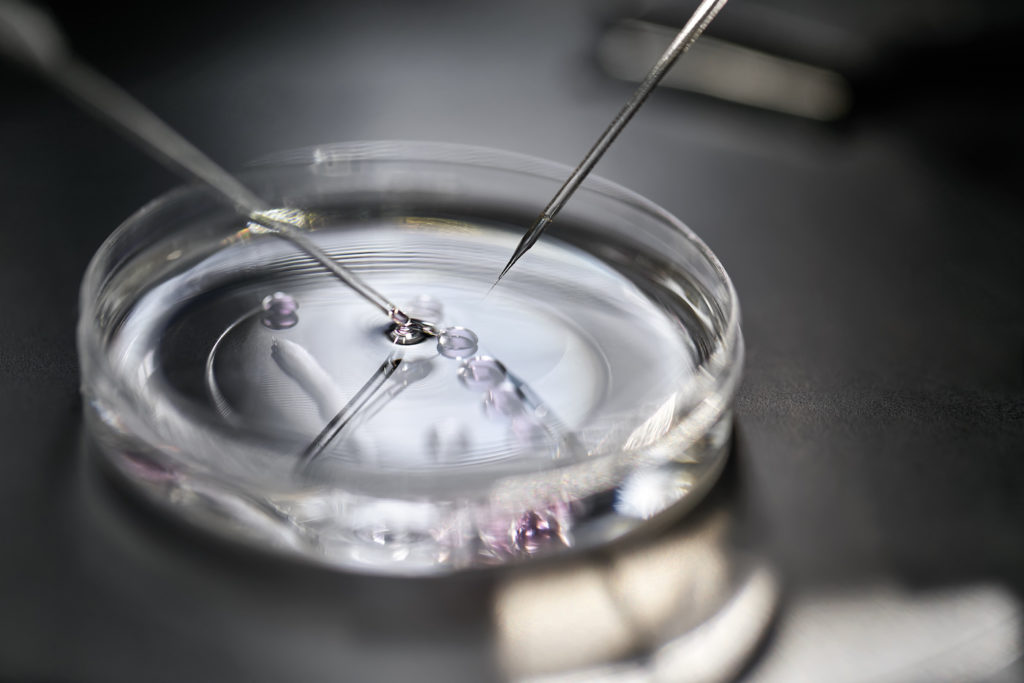

The process is now well established in our culture. Couples that cannot have biological children naturally (due to age, a biological issue, or because they are of the same sex); or individuals who simply want to have a baby “of their own” (who can purchase one or both gametes and also, if necessary, a gestater); or those who want to design a baby (fertility clinics now regularly offer sex selection through pre-implantation genetic diagnosis) now pay specialists to create embryos for them in a laboratory via in vitro fertilization (IVF) of ova by sperm.

“Excess” and unwanted embryos are very often produced in the IVF process. This is in part because the process is so expensive, and clinicians and parents want back-up embryos available if the first or multiple attempts at pregnancy fail. They are also created because in many cases aspiring parents want strict quality control over the project, such as selecting the sex and other genetic traits. One of three things happens to the “excess” embryos: (1) they simply get discarded and killed, (2) they are used for research and killed, or (3) they are frozen indefinitely. Astonishingly, there are now over a million embryos in that third category (a number that will only grow larger with time), the vast majority of which will not be used by the people who created them.

These embryos can stay viable for a very long time, as evidenced by the recent story of a Christian couple who adopted embryos created and frozen in 1992 and welcomed twins into their post-natal lives 30 years later. The couple already had four children, but these newborns are—in a very real sense—their oldest children. “I was 5 years old when God gave life to Lydia and Timothy,” said their father.

To many, though a bit outside the norm, embryo adoption looks like an obviously heroic act on the part of this adopting couple. Without them, Lydia and Timothy would have been killed or held in an absurd state—neither living nor dying. Kind of like a Han Solo frozen in carbonite who is never freed. It is unlikely that there will be enough adopters over time to come anywhere near to saving all of these tiny humans. But—much like the famous starfish thrower story—adoption certainly matters to thousands of other children saved by adoptive parents.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.Christian Duty to Embryos

Indeed, embryo adoption appears to be smack-dab in the center of the demands of the Gospel. This population deserves the closest attention from us. Our very salvation may depend on how we respond to these human beings—who, as Matthew 25 instructs us, are Christ for us. What we choose not to do for them we choose not to do for Christ. In a very real sense, if we choose to abandon these tiny humans, we choose to abandon Christ Himself.

Scripture also instructs us to seek liberty for the captives, and to allow the little children to come to Christ.

The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to proclaim good news to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim liberty to the captives and recovering of sight to the blind, to set at liberty those who are oppressed, to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor. (Luke 4)

Let the little children come to me, and do not hinder them, for the kingdom of heaven belongs to such as these. (Matthew 19)

And of course the Old Testament’s focus on care for the orphan is ubiquitous and simply assumed of those who walk in the way of the Lord:

The Lord is King forever and ever;

the heathen will disappear from his land.

You listen, O Lord, to the longings of the poor;

you strengthen their courage and heed their prayers.

You ensure justice for the orphan and the oppressed

so that no one on earth may fill them with terror. (Psalm 10)

In the Catholic context, the opening to Donum Vitae from the Congregation of the Doctrine of the Faith reminds us what is at stake here: “The human being must be respected—as a person—from the very first instant of his existence.”

Scripture and tradition, therefore, tell us something astonishing about our embryonic brothers and sisters currently being kept in frozen storage: they are a vulnerable population that perhaps demands our attention the most. Captives, orphans, and little children deserve and have received special consideration from the Church. So too do those deemed “less than full persons” or “non-persons” by the culture. Now imagine a human being who is a captive, an orphan, and a (quite) little child that the surrounding culture deems a non-person all in one.

What we choose not to do for frozen embryos, we choose not to do for Christ. In a very real sense, if we choose to abandon these tiny humans, we choose to abandon Christ Himself.

Ethical Debates over Embryo Adoption

Having seen the Christian basis for recognizing the full human dignity of orphaned embryos and our duties to them, we can now turn to some ethical concerns Catholics have raised about embryo adoption. Some argue that embryo adoption is morally unacceptable because, in their view, transfers (the process of implanting an embryo into someone’s womb) are intrinsically evil. Of course, Catholics are not consequentialists (the current leadership of the Pontifical Academy for Life notwithstanding): we do not do things that are intrinsically evil to save even frozen embryos. I was recently part of a plenary debate at the annual meeting of the Catholic Medical Association (CMA) on embryo adoption and, in the debate, I was clear: if our opponents could show that embryo transfers, even for this good end, are intrinsically evil, then we should try to find some other way to respect the fact that these embryos are little Christs.

This disagreement about embryo transfers among Catholics originates from a passage in Donum Vitae in 1987 before embryo adoption was possible: “In consequence of the fact that they have been produced in vitro, those embryos which are not transferred into the body of the mother and are called ‘spare’ are exposed to an absurd fate, with no possibility of their being offered safe means of survival which can be licitly pursued.” In 2008, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith would follow up with Dignitatis Personae, and here embryo adoption was explicitly considered. The CDF chose not to condemn it outright, but suggested that it has various unspecified (though serious) “problems” and that abandoned embryos represent a situation of injustice which in fact cannot be resolved.” (original emphasis).

Given the CDF’s refusal to explicitly condemn embryo adoption, it is not surprising that many Catholic theologians and philosophers who never dissent from the formal teaching of the Church have argued in favor of it. It is of course true that the fundamental injustice done to these children can never be fully resolved. But Catholic ethicists and theologians like Germain Grisez, Fr. Peter Ryan, Fr. Tom Berg, Thomas Williams, and more have shown (in a book published by the National Catholic Bioethics Center—a new edition of which is on the way) multiple ways to be faithful to the Church’s teaching while making moral space for rescuing and adopting embryos.

Those morally opposed to embryo adoption often suggest that it is akin to engaging in procreation apart from sex, and thus is an intrinsically evil act in violation of Humane Vitae. But while defending the connection between sex and procreation in marriage is extremely worthwhile in our current moment (again, especially the strange things happening with the Pontifical Academy for Life), in the case of a frozen embryo, the separation of procreation from sex has already been completed. The question is not whether we will continue procreating, but whether we will try to rescue an unimaginably vulnerable person.

Embryo adoption no more breaks the connection between sex and procreation than does giving a newborn child to a wet nurse for breastfeeding—or adopting children from foster care, or just after birth. Indeed, if caring for and sustaining a child at 23 weeks with one’s body is somehow understood to continue the procreative process, it follows that caring for and sustaining a child at 23 weeks in a NICU bed also continues the procreative process.

This is of course absurd. Tragically, and unjustly, procreation has already taken place by the time a couple makes a decision to rescue one or more embryos from their captivity. Citing Donum Vitae, the Catechism of the Catholic Church (no. 2275) says the following: “One must hold as licit procedures carried out on the human embryo which respect the life and integrity of the embryo and do not involve disproportionate risks for it, but are directed toward its healing, the improvement of its condition of health, or its individual survival.” That, in a nutshell, is what embryo rescue and adoption is.

Embryo adoption no more breaks the connection between sex and procreation than does giving a newborn child to a wet nurse for breastfeeding—or adopting children from foster care, or just after birth.

But even if embryo adoption isn’t intrinsically evil, there are still other moral hazards that can be tied to it. For instance, perhaps embryo adoption cooperates with the evil practices of IVF clinics. My partner in the CMA debate, Professor Kent Laskowski, responded to this concern with a wonderful analogy to the Church’s efforts to ransom captives (taken by pirates or other marauders) back in the day. Here’s the short version: the Church found a way (especially in the context of the Trinitarian and Mercedarian orders of high medieval Europe) to free the captives, even though it often involved paying ransoms to captors. Similarly, there are ethical ways to free embryonic captives. Embryo adoption is not intrinsically evil; contemporary theologians and philosophers should continue to work on ways to licitly free these captives—even if we face criticism for doing so, as those medieval orders did.

However, certain attitudes toward embryo adoption would amount to a cooperation with evil. It pains me to write this, especially as someone who has struggled with infertility in marriage and therefore knows this kind of agony firsthand. But we must avoid promoting embryo adoption as a kind of alternative when infertility presents itself. That unacceptably plays into the structures and logic of the fertility industry (which turns embryos into consumer commodities) and would be inappropriate cooperation with evil. If it is to be licit, embryo adoption must be about rescuing a captive—a paradigmatic member of the “least ones”—and letting them come to Jesus. Significantly for them, this appears to be exactly what was on the mind of the Christian couple that now has two 30-year-old newborn children. They were seeking to rescue, not to have children in light of infertility.

We must avoid is promoting embryo adoption as a kind of alternative when infertility presents itself.

Freeing Captives

If we are still resistant to this idea, perhaps we may need to ask ourselves whether we are fulfilling Donum Vitae’s command to treat our embryonic brothers and sisters as persons just like us. Do we really believe that there are over one million little child orphans being held captive at the moment in the United States?

I don’t need to remind Public Discourse readers about the utmost importance of our witness in the post-Dobbs world. Of course, this witness is not the primary reason to adopt embryos. But one of the first places our opponents in the abortion debate go in their arguments is to the human embryo. They go there to show that we don’t really think the prenatal human being counts the same as other human beings. So our witness to their full humanity, while so important before, is even more important now.

Many of our embryonic brothers and sisters have been unjustly made captives. If done for the right reasons, it can be licit for Catholic couples to rescue and adopt them. Let us work hard to find that licit space for such rescues to take place.