Last week, the Supreme Court declined to grant religious exemptions to Maine’s COVID-19 vaccine mandate for health care workers. This decision has intensified debate about whether people of faith should seek religious exemptions to these mandates and in which circumstances such exemptions should be granted. More than a cursory look at the constitutional and legal questions of these mandates is beyond my expertise. But I can suggest how those individuals with moral questions, especially Catholics, should approach this issue.

The popular mantra “you do you and I’ll do me” is useless in medical practice because decisions about medical care involve both the person providing the care and the person receiving it. The ethical choices of each party are so deeply intertwined that conflict is sometimes unavoidable. It can be challenging at times, but our country has long recognized both the provider’s and the patient’s right to seek legal protection for their religious beliefs. All Americans, and frankly all morally serious people anywhere, should be extremely leery of any action or proposed law that suggests unreasonable limits on this fundamental right.

Religious Freedom and Its Legal Limits

Religious freedom, however, is not now and has never been a “get out of jail free” card. Numerous legal decisions have confirmed the fact that there are limits to what any individual or religious congregation can do in the name of their faith. In 1879, in Reynolds v. United States, the courts upheld the federal ban on polygamy, regardless of religious faith, stating that “the Free Exercise Clause forbids government from regulating belief, but does allow government to punish activity judged to be criminal, regardless of an activity’s basis in religious belief.” The case established that one’s professed beliefs do not automatically or unilaterally supersede the law of the land. If they could, government would be meaningless—each person could define his or her supreme law and call it religion.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.Other cases limited the wearing of yarmulkes if it prevented appropriate donning of military equipment (Goldman v. Weinberger in 1986) and allowed a state to deny an individual unemployment benefits if he was fired for illegally ingesting peyote during a religious ceremony (Employment Division v. Smith in 1990). As Judge Learned Hand wrote in his 1953 decision Otten v. Baltimore and Ohio R. Co., “The First Amendment . . . gives no one the right to insist that in pursuit of their own interests others must conform their conduct to his own religious necessities.” None of these cases provides direct guidance on the question of religious freedom and vaccine mandates, but they do clearly show that the idea of permissible limits on religious freedom has a lengthy and instructive legal history.

The courts have also addressed the question of vaccine mandates in the past. When a smallpox epidemic swept through Massachusetts in the early years of the twentieth century, the smallpox vaccine was mandated (as well as now-familiar social distancing measures—business, school, and church closures). One man was opposed to receiving the vaccine and took the issue all the way to the Supreme Court in Jacobson v. Massachusetts, 1905. The Court enforced the mandate, creating what is now called the “reasonableness test,” and confirmed that “the rights of the individual in respect of his liberty may at times, under the pressure of great dangers, be subjected to such restraint, to be enforced by reasonable regulations, as the safety of the general public may demand.” The case established a precedent that vaccine mandates can be enforced despite individuals’ moral objections.

Religious freedom is not now and has never been a “get out of jail free” card. Numerous legal decisions have confirmed the fact that there are limits to what any individual or religious congregation can do in the name of their faith.

When Can Religious Beliefs Exempt Us from Vaccine Mandates?

Knowing that the law places legitimate limitations on religious freedom, we can now examine the circumstances under which religious freedom exemptions are justified. More specifically, we can consider the following question: when is it reasonable or appropriate to use religious freedom as a justification to claim exemption from a mandate to receive the COVID-19 vaccine?

Religious freedom should not be invoked because an individual has concerns about the efficacy of the vaccine. That is a scientific evaluation. Nor should religious freedom be invoked because someone believes COVID-19 to be a government conspiracy. Religious freedom should not be cited as a defense against perceived governmental overreach. These are political stances. Each of these concerns may or may not be valid, but they are not specifically religious or faith-based concerns. Such concerns should be addressed through channels of political debate and legal recourse, not through seeking religious exemptions.

Could an exemption from a mandated COVID-19 vaccine be mounted on religious freedom grounds by an individual who has specific concerns regarding the ethics of how a vaccine was created, tested, or produced? Many of the world’s religions have specific moral and theological teachings that pertain to medicines and medical research.

For Catholics, the question of the use of fetal cell lines in vaccine development has been a long-standing concern. The Pontifical Academy for Life addressed this very concern over fifteen years ago amid concerns about a rubella (German measles) vaccine that was produced using human cell lines developed from fetal cells obtained from an abortion. Their statement is very clear: “[V]accines with moral problems pertaining to them may also be used on a temporary basis. The moral reason is that the duty to avoid passive material cooperation is not obligatory if there is grave inconvenience. Moreover, we find, in such a case, a proportional reason, in order to accept the use of these vaccines in the presence of the danger of favoring the spread of the pathological agent, due to the lack of vaccination of children.”

The same line of moral reasoning was further explored when the Congregation for the Doctrine of Faith (CDF) issued the Instruction Dignitas Personae, which reaffirmed that individuals may use vaccines developed with the use of immorally obtained cell lines, if a sufficient risk is posed 1) to the health of the individual receiving the vaccine or 2) to the common good. These documents laid the foundation for the “Note on the morality of using some anti-COVID 19 vaccines” issued by the CDF this past year.

The Note clarifies two critical points: first, all Catholics are required to conduct their lives in a way that upholds the dignity of all human life, including the life of the unborn. There are no exceptions to this moral requirement. This means that all Catholics, regardless of whether they receive a COVID-19 vaccine, should be working toward and praying for alternative research methods. Second, the realities of pharmaceutical drug and vaccine development in our current medical situation mean that, for the individual Catholic, receipt of the Pfizer or Moderna COVID-19 vaccine (the development of which involved testing using fetal cell line HEK293) would constitute passive material cooperation and is morally licit in the absence of other options.

The CDF Note on COVID-19 vaccines is also quite clear in its declaration that vaccination should be optional, and that there can be individuals who will be justified in refusing to receive a COVID-19 vaccine because of concerns of conscience. But equally clear is the two-part decision-making tree set forth in the Note, specifically that one’s conscience must be well-formed and that those who decide against vaccination must act in a way that minimizes the chance that their actions will contribute to the continued spread of this disease.

Passive Material Cooperation in Everyday Products

A well-formed conscience involves taking an honest look at how pervasive the use of pharmaceuticals tested on illicitly derived fetal cell lines is in our daily lives. It also means assessing in what other ways Catholics may be engaging in passive material cooperation with evil without even realizing it. Tylenol, Advil, Benadryl, Tums, and Sudafed (all over-the-counter medications) and Albuterol, Azithromycin, and Ivermectin (prescription medications)—to name just a few—have the exact same level of testing involving HEK293 as the Pfizer and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines.

There are likely vanishingly few individuals who apply the rigorous ethical criteria they use against the COVID-19 vaccine to the rest of their medical and personal decisions.

There is virtually no public outcry among Catholics against the use of these medications, however. And as discussed above, the receipt of the Pfizer or Moderna COVID-19 vaccines, given their particular association with HEK293, is an example of passive material cooperation. Whether aware of it or not, many of us engage in passive material cooperation with abortion on a near daily basis. As pointed out by Fr. Matthew P. Schneider, in his Patheos article “12 Things Less Remote from Cooperation in Evil than COVID Vaccines,” Energizer batteries, Heinz Ketchup, and Doritos are all made by companies that provide direct financial support to Planned Parenthood. Wells Fargo, Bank of America, and American Express do the same. As Fr. Schneider notes, we are fortunate that the Catholic Church has a long and well-developed moral theology that provides a framework for making accurate and logical assessments of difficult situations. It is not ethically defensible to observe ethical principles in some cases but not others when the principles are equally applicable in both.

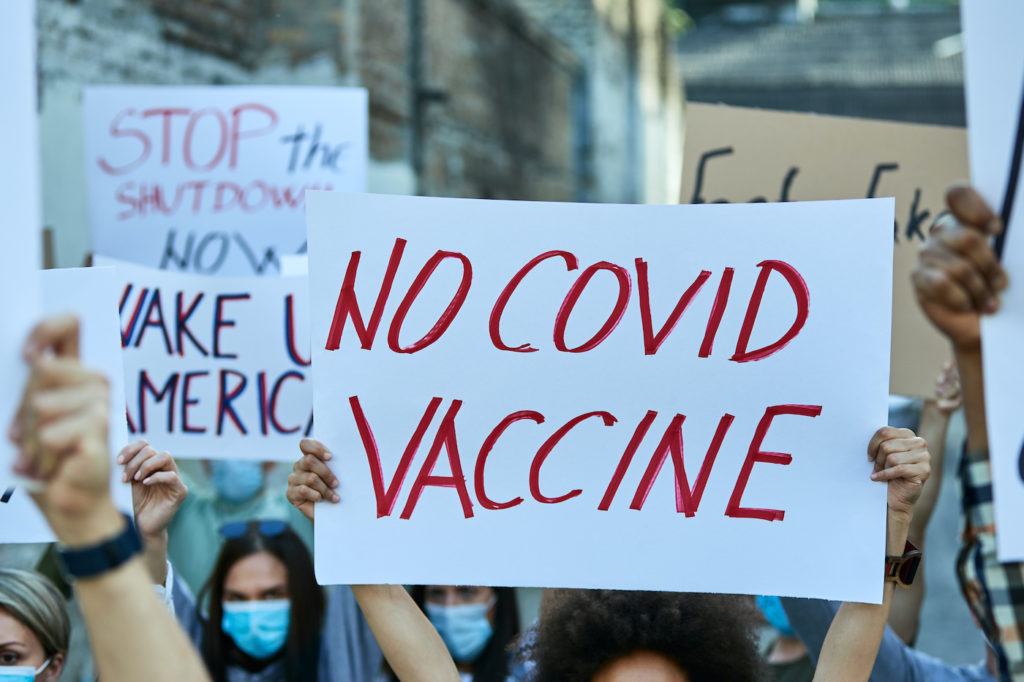

“Religious Exemptions” to the COVID-19 Vaccine Are Usually Dubious

Why, then, do I think that invoking religious freedom to avoid the COVID-19 vaccine is almost always problematic? My concern is twofold. First, because there are likely vanishingly few individuals who apply the rigorous ethical criteria they use against the COVID-19 vaccine to the rest of their medical and personal decisions. Second, because many of those who refuse the COVID-19 vaccine are not following the explicit guidelines of the Catholic Church to take extra precautions against spreading the virus—namely by wearing face masks and social distancing.

This combination of inconsistency and irresponsibility endangers the long-term cause of religious freedom. It cannot be defended, and it does not go unnoticed by those seeking to limit religious freedom in medical practice as a whole. When individuals refuse vaccination against COVID-19, claim they are doing so because of their Catholic faith, make no effort to apply those same standards to the myriad daily decisions that involve passive material complicity with evil, and do little to protect the vulnerable around them, they are supplying ammunition to those who argue that religious freedom is a threat to modern society.

Medical practitioners of faith are currently facing intense pressure to check religiously-informed moral convictions at the clinic door. When an OB-GYN is fired from her practice for refusing to perform tubal ligations, when a physician assistant is terminated for refusing to prescribe emergency contraception to a patient in a Catholic practice, and when a pediatrician is sanctioned for not providing puberty-blocking hormones to a young child expressing gender dysphoria, these practitioners depend on cultural legitimacy and legal protection to acquire recompense under their First Amendment rights. The inconsistent application of religious freedom principles in the COVID-19 vaccine debate threatens to significantly weaken the desperately needed protections for Catholic medical practices.

Can an individual refuse the COVID-19 vaccine for religious reasons and be justified in doing so? I think the answer is yes, based on the primacy that Catholic moral teaching places on the conscience and free will. But that individual has an enormous burden to bear: he or she must then consciously and carefully avoid any other product that is similarly associated with HEK293 and take effective measures not to contribute inadvertently to the spread of the illness—consistent use of masking in crowded or indoor places, frequent testing for COVID-19 to avoid unknowingly being an asymptomatic carrier, strict quarantines after close contact with a COVID-infected individual. To the person who follows these guidelines, I will gladly defend your religious freedom. To everyone else, you are abusing your First Amendment rights and potentially doing irreparable harm to conscience protection and religious freedom in medical practice.