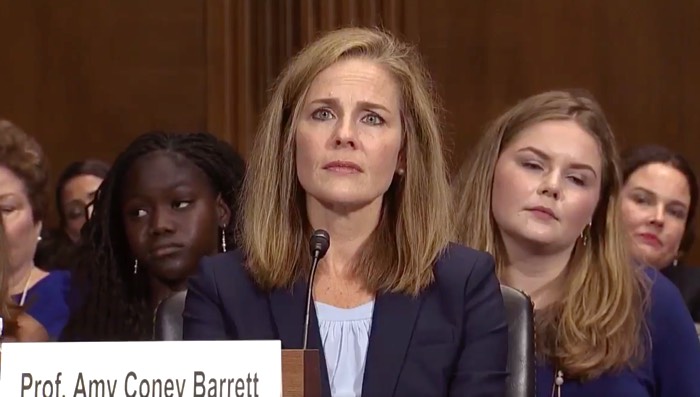

During Amy Barrett’s recent confirmation hearing for Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals, Senator Chuck Grassley posed the following question to the nominee: “When is it proper for a judge to put their religious views above applying the law?”

Barrett replied, “Never. It’s never appropriate for a judge to impose that judge’s personal convictions, whether they derive from faith or anywhere else, on the law.”

Barrett’s answer deserves significant attention. As C.C. Pecknold understands, the overarching question that pervaded much of the confirmation hearing concerns the nature of political theology. In the modern liberal account, law is considered to be secular, devoid of any religious influence or reference to the divine. The deepest worry here is that Barrett will impose her “personal religious convictions” as the standard for either applying or undermining the law.

Augustine’s Doctrine of the Two Cities

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.Opponents of Barrett’s appointment fear that she holds an understanding of politics and faith that corresponds to a type of unity, a political theology whose judgment regarding the law comes from a divine, not secular, source. This supposition corresponds with Senator Diane Feinstein’s remark that Barrett’s religious faith is a dogma that “lives loudly within” her.

The image could not be clearer: liberal political thought inaugurated the needed division between politics and religion. Amy Barrett appears to be aiming for a union of politics and religious faith. What is at stake here is the very achievement of modern liberal democracy itself.

The irony in such a narrative is that, in fact, Barrett is the one arguing for the truth that religion and politics need to be separated. And this impetus towards seeing the separation between religion and politics comes, for Barrett, precisely as the result of her Catholic faith.

The Catholic Church teaches that the salvific message of Jesus Christ transcends the political; salvation is not dependent upon the condition of one’s political society. The fullest meaning of Christianity ensures that the spread of its healing doctrine not be tied to a political regime. To be a citizen of a particular political order does not make or break one’s eternal beatitude. Salvation can be had in any type of regime, be it good or bad.

At the same time, as St. Augustine argues in the City of God, patriotism may be an obstacle to our salvation. Augustine was certainly a realist in affirming that most regimes would fall short of justice. This is why he drew such a sharp distinction between the City of God and the City of Man. The City of God is a transpolitical reality, and something to which human beings are ordered as their ultimate end. Following in the footsteps of Plato and the classical tradition of political philosophy, Augustine believed that it was necessary to ask what the best regime would be. Yet he also agreed with Plato that such a perfect regime is impossible to create in this life and that attempting to bring it about would destroy actual regimes.

In his letter to the Emperor Anastasius, Pope Gelasius I articulated this twofold distinction between the spheres of religion and politics. For Gelasius, political authority is honorable, and given for the purpose of having care for human affairs in the temporal order. However, in matters that transcend the polity, a political ruler needs to recall that he shall “bow [his] head humbly before the leaders of the clergy and await from their hands the means of [his] salvation.” While acknowledging the legitimacy and necessity of the political order, the Pope is nonetheless echoing Augustine in upholding the supremacy of the religious and transpolitical sphere. Political rulers must take care not to impose their will and authority over spiritual matters that are the proper sphere of the Church.

The City of God and Man Become One

For all our contemporary invocations of the separation of church and state, this distinction between the City of God and the City of Man has actually been undermined in modernity. Describing Augusto del Noce’s insights into the modern age, Michael Hanby observes that, for Del Noce, modernity is

predicated upon the attempted elimination of every form of transcendence: the transcendence of truth over pragmatic function, the transcendence of the orders of being and nature over the order of historical construction, the transcendence of the civitas dei over the civitas terrena, the transcendence of eternity over time, the transcendence of God over creation. Every form of transcendence save one, that is. For once real transcendence is eliminated or suppressed, political order itself becomes the transcendental horizon, assuming sovereignty over nature, truth, and morality—over anything that would precede, exceed, and limit it.

This elevation of the political order as supreme is one of the first principles of the modern age. Praxis usurps the primacy of the contemplative or theoretical order as being the highest good for human life. What follows logically from this principle will be that the political order reigns supreme.

The foundational claim of modern political thought is that it inaugurated the separation between religion and politics. This is how we have been instructed to read modern political thinkers such as Machiavelli, Locke, and Hobbes. Yet there is a strange anomaly in this narrative of modern thinking.

In Leviathan, Thomas Hobbes goes so far as to argue that scripture supports a combination of politics and religion. Yet the last two parts of Leviathan reveal that Hobbes is not writing about a rational, secular political order. Instead, Hobbes is writing in the arena of political theology precisely as a theologian. Understood in this context, it may be surprising to discover that Hobbes’s primary intellectual target is the Jesuit theologian Robert Bellarmine. Why? Bellarmine was arguing for the Augustinian position that the spheres of politics and religion were not the same.

In his Letter on Toleration, John Locke initially sounds as if he is endorsing such an Augustinian understanding, arguing that the spheres of politics and religion are utterly separate and immovable. He warns against jumbling “heaven and earth together,” those two societies that “are in their original, end, business, and everything, perfectly distinct and infinitely different from each other.” Yet Locke’s fundamental understanding regarding the purpose of religion actually aligns quite well with the overarching aims of a liberal political order. Toleration, according to Locke, is the very substantive core of the gospels.

Thus, in both Hobbes and Locke, the supposed division between politics and religion has collapsed: the political and the spiritual are brought together, and such a joining is ultimately confirmed in the name of religion.

Is Catholicism Safe in Modern Liberal Democracy?

In his illuminating 1998 essay, “Transforming Constitutionalism and the Case of Religion: Defending the Moderate Hegemony of Liberalism,” Princeton political theorist Stephen Macedo makes the following observation about modern liberal democracy and its relationship to American Catholicism in particular:

We might almost say that American Catholics (though perhaps not Fundamentalists as of yet) have come to accept the American rather than the Catholic position on the separation of church and state. To be American is to have a religion (we have very few village atheists these days), but any religion at all will do.

In assessing the kind of struggles that Catholic candidates for public office have had to endure, Macedo goes on to claim that the litmus test for such service must presuppose “the practical meaninglessness of their religious convictions.” In other words, Macedo claims that religious practice will inevitably disqualify one from public office since, following the liberal stance, religion and politics are utterly separate. However, this outward appearance of separation neglects a more subtle reality that may be overlooked: religious practice would be acceptable insofar as it holds to the liberal position of toleration and any of its other ultimate “virtues.” What makes religious conviction “practically meaningless” stems not from a separation of politics and religion. Rather, religion becomes subsumed within the political. Religious practice will be allowed space if its aims are tied with the principles of modern liberal politics.

And so we return to Amy Barrett and her political interlocutors. Barrett was pressed about whether she considers herself an orthodox Catholic. This is the central question, not just for her, but for our entire political and social order. Perhaps it will provoke us to reconsider the degree to which orthodox Catholicism can truly be tolerated in modern liberal democracies. The argument that needs to be heard, for the health of both religion and politics, insists that the things of Caesar and those of God are not the same. For Barrett, this teaching is at the heart of the Catholic faith, and it is thankfully a dogma that lives loudly within her.