The escalation of politically motivated violence in America today raises important questions about the nature and scope of our constitutional right to speak freely. To fight political correctness, it is more crucial now than ever to promote a legal and cultural climate of robust intellectual and political dialogue. However, defenders of free speech should resist adopting the simplistic formulations of this freedom advanced by current Supreme Court jurisprudence.

As the recent debacle in Charlottesville illustrates, an absolutist reading of the first amendment makes it difficult for responsible citizens and their governments to make prudent decisions about how to uphold law, order, and genuine liberty against very real threats to these fundamental goods. Recapturing a reasonable view of free speech requires us to revisit the original understanding of this constitutional clause. Its wisdom becomes even clearer in light of the Socratic account of reason and freedom underlying our legal order.

Charlottesville and Free Speech Absolutism

Due to reigning judicial interpretations of the first amendment, the city of Charlottesville, Virginia, was unable to decline a request on behalf of white supremacists to march in protest of its decision to rechristen a park formerly honoring Confederate General Robert E. Lee.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.As evidence mounted that the convergence of protesters and counter-protesters in the city’s downtown area was likely to pose unmanageable threats to public order, the city sought to move the demonstration to a safer location. In the blink of an eye, United States District Judge Glen E. Conrad issued a preliminary injunction, forcing the city to permit the confrontation to occur in the heart of town. As feared, violence erupted, culminating in the vehicular slaughter of one counter-protester and serious injury of nineteen others by a rallygoer.

Though blame for the events in Charlottesville lies with those who promote, condone, or commit violence in the name of racist ideologies, a constructive response demands that we examine the underlying causes contributing to this and similar dysfunctions in contemporary politics.

To begin with, Americans are witnessing the rise of factions passionately committed to ideas and methods incompatible with the regime of ordered liberty enshrined in our laws and traditions. On one side are those who deny the human dignity and civil rights of their non-white fellow citizens. On the other are those who regard American political society as fundamentally “fascist,” and who arrogate to themselves the right to use force to stifle any speech they deem unacceptable. Finally, we have a judiciary eager to impose rigid readings of complex concepts on political authorities struggling to uphold the common good in the face of these troubling trends.

Does our constitution really mandate what happened in Charlottesville? Or is there a better way to understand freedom of speech and its relation to personal freedom, civic responsibility, and the common good?

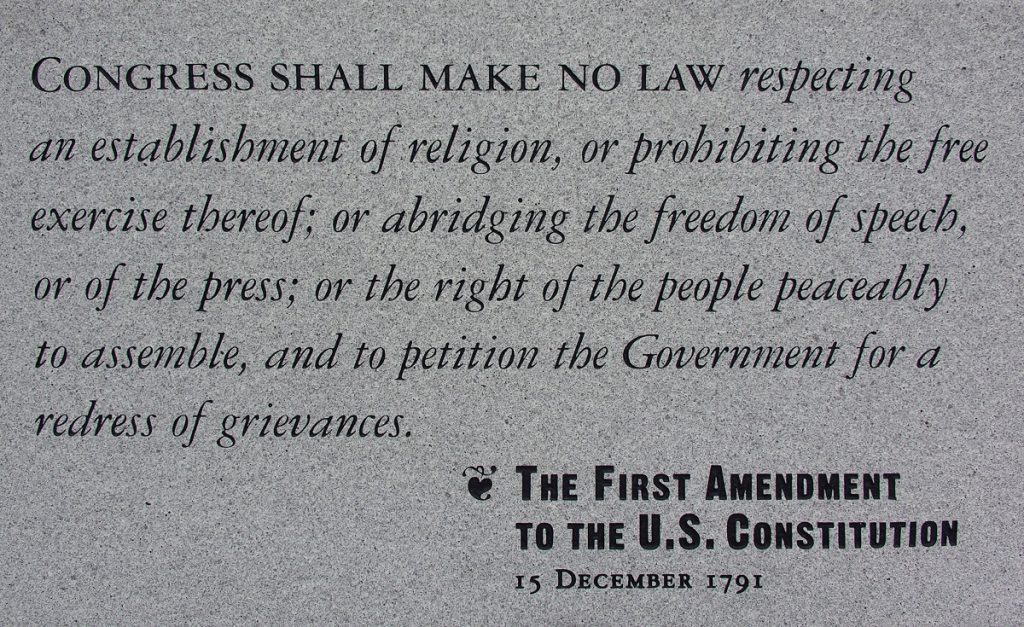

In his classic Commentaries on the Constitution, Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story stresses that to read the first amendment’s free speech clause as “intended to secure every citizen an absolute right to speak, or write, or print, whatever he might please, without any responsibility, public or private, therefor, is a supposition too wild to be indulged by any rational man.”

Though contemporary jurisprudence does not entirely ignore the need to place freedom of speech within a reasonable framework, its relentless slide toward rights absolutism does come painfully close to adopting this wild and irrational view. Re-reading Story in light of the tradition that informed him will equip us to promote freedom of speech for what it truly is: a component of ordered liberty.

Socratic Reason and the Foundations of Freedom

In ancient Greek, the word for speech is also the word for reason: logos. Logos is the faculty by which human beings grasp the natural order of things, which, being itself a product of divine Logos, reveals what is objectively good. Since man is rational and reason aims at the good, Socratic political philosophy rests on the bedrock principle that right reason ought to rule the actions of men, both personally and politically.

As Socrates makes clear in Plato’s Republic, what is harmful—for example, returning a weapon to its lawful owner when he is raving mad—cannot be just. On similar grounds, we can doubt whether money, property, or political authority truly belong to those whose habits of bad reasoning cause them to use these things to harm themselves or others. In Socrates’ admittedly fanciful “city in speech,” the ruling classes are deprived of all property and forbidden to use money, and authority belongs exclusively to philosophers whose dedication to reason and the good has proved unshakable.

Socratic thinkers such as Aristotle and Cicero, intent on influencing the actions and institutions of real political actors and societies, readily admit that the possession of property and power by non-philosophers is a practical necessity. The core challenge of politics, from their perspective, is to employ a set of tools—such as laws, institutions, rhetoric, education, and the arts—to encourage the virtuous use and discourage the abuse of property and power.

In government, this Socratic strategy requires a system of power sharing in which citizens, lawmakers, executives, and judges contribute what is best in their own thinking while deferring to what may be better in that of their fellows. Though there is no magic formula by which good laws can lead a “race of devils” to the common good, Socratic politics does attempt to guide free but fallible citizens toward an approximation of divine Logos applied to human affairs.

The Socratic case for freedom of speech does not imply that speech is worthy of protection when it tends to undermine public order; such speech should, if necessary, be punished in accordance with due process of law. As it happens, allowing for certain important modifications—such as the disestablishment of religion and the rejection of prior censorship—this is precisely how Justice Story understood the nature and scope of the first amendment’s free speech clause.

By the time our Constitution was drafted, common law wisdom had settled on the doctrine of “no prior restraint,” according to which citizens may publish their views without prior government approval, but are subject to criminal and civil liability when their words are subsequently proven to damage legally defined private rights or to undermine public order.

Story clearly affirmed that republican self-government is impossible if the citizens are not free to discuss affairs of state critically. He also insists that the failure to protect personal rights and public peace from malicious speech undermines the purposes and the institutions of free government, ultimately paving the way for despotism.

Charlottesville and the Recovery of Socratic Realism

In the case of Charlottesville, no government body questioned the right of white supremacists to air their views, however reprehensible, or to do so while exercising their first amendment right “peaceably to assemble.” As the word “peaceably” implies, however, the right of assembly is no more absolute than the right to speak freely, and the preservation of the lives and liberties of all citizens demands that assemblies be subject to prudent regulation by authorities responsible to the people. As Mayor Mike Singer pointed out, “Government has no more central duty than protecting life and property,” and relocating without prohibiting a gathering of mutually hostile citizens was an attempt to perform that duty while giving full scope to first amendment rights.

Why was the city obstructed in its duty? Judge Conrad admitted that preliminary injunctions are “extraordinary,” endowing courts with “very far-reaching power,” and hence “to be granted only sparingly and in limited circumstances.” Those circumstances apply when the court finds that a plaintiff is “likely to succeed on the merits,” likely to “suffer irreparable harm,” and enjoys “the balance of equities” in the matter at hand.

Based on decades of Supreme Court precedent, Conrad reasoned as follows: since the first amendment requires governments to be strictly “neutral” as to the content of speech, since the city evidently disagreed with the content of the rally in question, and since the city could not prove (overnight) to the court’s satisfaction that it had “neutral” reasons for moving the rally, it was fair to assume that the petitioner would prevail on further adjudication. Since every undue restriction of first amendment rights automatically constitutes “irreparable harm,” and since the “balance of equities” always privileges first amendment rights over other concerns, the “extraordinary” measure of overriding the city’s prudent adjustments to a white supremacist rally was constitutionally necessary.

Judge Conrad’s opinion demonstrates how far contemporary jurisprudence has drifted from the Socratic realism underlying our constitutional order. In truth, it is neither necessary nor possible for government to be “neutral” toward the content of speech that is repugnant to the purposes for which government exists. If the Charlottesville protesters are right, the premises of the first amendment are false, and the very rights they claim are without foundation. This doesn’t negate their rights, but only because our government, on decidedly non-neutral grounds, rejects the content of their speech.

Pretending that our government is neutral actually undermines our rights, since a government that enforces manmade “rights” while denying their basis in reality moves dangerously close to using force without right—the very essence of tyranny. A non-neutral government can and must be impartial in allowing maximum scope to freedom of speech, but only for the non-neutral purposes of furthering a common good that may also demand certain restrictions on manifestly harmful speech.

To claim that the genuine first amendment rights of white supremacists suffer irreparable harm when they are asked to vent their falsehoods in one public place instead of another, or that minuscule restrictions on free speech automatically outweigh serious concerns about public safety, is self-evidently wrong. Self-evident errors cannot be law.

Although courts can and must ensure that the people and their elected representatives respect genuine constitutional rights, those rights must be reasonably construed, or else the courts’ interference amounts to the very despotism from which the Constitution is meant to protect us. A recovery of the Socratic wisdom informing our constitutional rights will enable us to promote genuine freedom while doing our best to protect the lives and welfare of the citizens whose liberties we so cherish.