Seventeen years ago, I received a phone call from Norma McCorvey. “I will do anything to overturn my decision in Roe v. Wade,” she told me—and she asked me to help her.

Norma, of course, was the plaintiff referred to as “Jane Roe” in Roe v. Wade, the case in which the United States Supreme Court interpreted the Fourteenth Amendment of the United States Constitution to mean that the states of our nation were forbidden from prohibiting or meaningfully regulating or restricting abortion.

Shortly thereafter, I received a call from Sandra Cano, who was the plaintiff in Roe’s companion case, Doe v. Bolton. Doe, which was decided on the same day as Roe, may be less known by the general public, but it is considered equally noteworthy to constitutional scholars and pro-life commentators. The Roe and Doe cases were the two pillars on which all subsequent abortion jurisprudence rested.

In that telephone call, Sandra Cano told me that she had suffered deep guilt and remorse in the previous twenty-seven years over the Doe decision. She wanted my help to get her decision overruled, and she told me that she could not rest until she helped correct what she viewed as a great injustice to the women and children of this nation. Both women knew me to be an attorney who litigated constitutional issues and who represented the rights of mothers, including mothers who lost their children in abortions performed without truly voluntary and informed consent.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.With the news of Norma McCorvey’s death on Saturday, Sandra and Norma are now both gone. It is natural for those of us who knew them to reflect on their experiences and the meaning of what they did, who they were, and ultimately what they fervently wanted to accomplish by the end of their lives.

Exposing the Weakness of Abortion Jurisprudence

When I received those calls from Norma and Sandra, I had a case going to the United States Court of Appeals on behalf of a mother who had lost a daughter who died in utero. The Roe and Doe decisions had influenced New Jersey law in such a way that those decisions stood in the way of my client being able to redress her grievance.

Norma and Sandra wanted to address the courts to weigh in on the pro-life side supporting women and their children. So I called Allan Parker, a seasoned attorney who had founded the Justice Foundation in San Antonio, Texas. I told him they wanted representation to file amicus briefs in our case. Allan agreed to represent them, and Norma, Sandra, Allan, and his legal staff, including Clayton Trotter, all went to work to prepare a legal presentation consistent with our own. It focused on the ways that abortion, as practiced after Roe and Doe, harmed not just children but also the rights and interests of mothers.

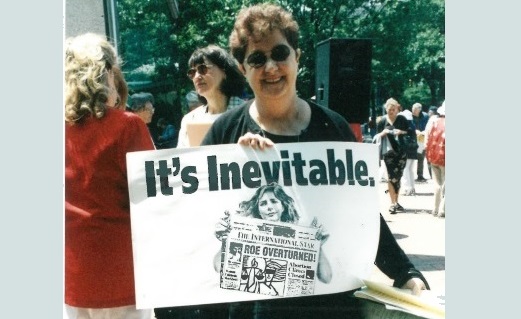

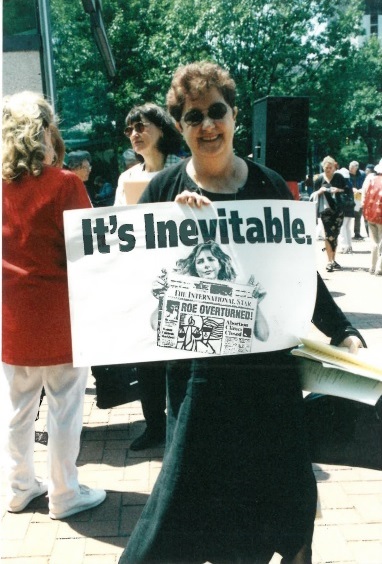

The other day, after I heard the news of Norma’s death, I looked at some photographs taken in front of the Liberty Bell in Philadelphia, across from the federal courthouse, where they each walked in their amicus briefs and filed them with the court. We held a press conference that day, and their supporters held a rally in front of the Liberty Bell. Norma, Sandra, Clayton Trotter, and I all spoke to the crowd. I found two pictures that stood out.

In the first, Norma addresses the crowd while Sandra waits behind her to take her turn. This picture marks the first of many times that the two of them would collaborate to address the courts.

The second photo is particularly poignant. In it, Norma McCorvey is standing in front of the Liberty Bell holding a large poster containing a drawing of a young woman holding up a newspaper. Above the drawing of the woman, in large bold letters, it reads “It’s Inevitable.” In the picture below those words, the young woman is holding up a newspaper with the bold headline “Roe Overturned.” In a subhead, the newspaper states “Women Celebrate Worldwide.”

In that photo, Norma is smiling in a way she rarely did. That filing and the rally across from the courthouse uplifted both women and gave both hope that they would succeed in undoing the harm they felt responsible for helping to bring about. That one photo captures and symbolizes Norma McCorvey’s heroic efforts of the last twenty years of her life.

Later, Allan Parker, Clayton Trotter, and the Justice Foundation represented both women in Rule 60 motions they filed in the original Roe and Doe cases. Each woman asked the Court to vacate its judgment in her case on the grounds that both judgments were unjust to women and children. I supported Sandra’s and Norma’s efforts not because I thought they would result in a reversal in those cases but because Norma and Sandra exposed the shocking weakness of the Court’s decisions.

The Fraudulent Case of Doe v. Bolton

The details of the Doe case are particularly appalling. Though her case paved the way for millions of women to abort their children, Sandra Cano herself never wanted an abortion. While going through divorce proceedings, she thought that her parents had hired a lawyer to help her fight for custody of her four children and the fifth child she carried. When she found out that her lawyer scheduled an abortion for her and filed the complaint in Doe v. Bolton, which stated that Sandra wanted an abortion and had been denied one by the state of Georgia, Sandra fled to Oklahoma to avoid being pressured into having an abortion she did not want. She returned only after her lawyer and her mother assured her she would not have to abort her child.

There was no record in Sandra’s case: no written discovery, no interrogatories, no document requests, no depositions, and no expert reports. When I read the transcript of the argument before the three-judge panel, I saw that the attorney general of Georgia argued to the court that they needed discovery. The court, being so anxious to make law, told him they saw no reason to bother.

When the attorney general pointed out that the court didn’t actually “know if ‘Mary Doe’ is even pregnant,” the judges said they would just assume that she was. It didn’t occur to the attorney general that “Mary Doe” might in fact be pregnant but might never have asked the doctors for an abortion—because she didn’t want one. Had Sandra been deposed in the case, her true desires would have been revealed, the case would have been dismissed, and there would never have been a decision by the Supreme Court in Doe v. Bolton.

Sandra’s attorney, Margie Pitts Hames, convinced Sandra to sit in the back of the courtroom that day. Sandra told me she agreed to this because she wanted to return to Georgia and see her four children. Hames never spoke to Sandra again. Sandra did not know what was going on in the case until she saw a television news commentator announcing the Supreme Court decision on January 22, 1973.

Sandra grieved over that decision for years. She decided to get a copy of the file in her case to review it. The Court would not give it to her, because everything was filed under seal. She retained an attorney who filed a motion to permit Sandra to obtain copies of what was filed on her behalf. The motion was opposed by Margie Pitts Hames, who didn’t want Sandra to see the filings. Eventually the Court ruled in favor of Sandra, and she then discovered that the entire record was nothing other than a single affidavit purporting to be her own sworn statement. Sandra’s signature was found on an affidavit that stated that she wanted an abortion, had gone to a hospital seeking an abortion, and the doctors refused to perform one.

Sandra’s signature was forged. The entire case was a fraud on the Court—fraud that could have been easily detected but for the Court’s decision to decide the substantive issues without any kind of factual record or record containing discovery of any kind.

Roe and Casey: Upholding a Wrongly Decided Precedent

In Norma’s case, the entire record consisted of a single affidavit that Norma signed but never read. Norma met with her attorney only twice. The first time, they met in a bar over a pitcher of beer to discuss Norma’s willingness to be a plaintiff. The second time, Norma signed the affidavit.

Norma, whose education never went beyond freshman year of high school, later testified that she never knew or understood what an abortion was. She thought that the procedure just prevented a human being from coming into existence, like birth control.

It wasn’t until the mid-1990s, when she worked at an abortion clinic, that Norma started to understand what an abortion really was. One day she was in the “Parts” room, where parts of the babies, like limbs and heads, were brought after the unborn children had been aborted. It was then that Norma realized that abortions terminated the lives of actual living human beings. Soon after, she had her conversion to the pro-life side and, in 1997, started her ministry: “Roe No More.”

In 1992, the Supreme Court reaffirmed Roe in Casey v. Planned Parenthood, which was a two to three to four decision. In other words, four Justices held that Roe v. Wade had been incorrectly decided. Only two Justices unequivocally held that Roe was correctly decided as a matter of constitutional jurisprudence.

The other three Justices, in what was called the joint opinion, upheld Roe on the basis of the doctrine of stare decisis: even if the Roe decision was wrongly decided, they argued, the principle of precedent meant that the Court had to be consistent in its decisions. The three justices somehow reasoned that the exceptions to stare decisis—like those found in more than 240 prior cases in which the Court overturned its own prior decisions—did not apply to Roe.

Abortion Hurts Women

I remember the day I walked with Allan Parker and many others across the street in Dallas, Texas, to the US District Court to file Norma McCorvey’s Rule 60 motion. In her motion, Norma asked the court to reverse its judgment in Roe because the facts she learned after that case revealed that the judgment was unjust to both pregnant women and their children. With the help of her legal team, Norma filed six thousand pages of documents that demonstrated that abortion was harmful to women. Two thousand women who had had abortions submitted affidavits describing how their abortions ruined their lives.

The following year, Sandra Cano filed her Rule 60 motion in Doe v. Bolton. When I saw her that day, she looked genuinely happy to finally be able to correct the record in that case. She filed her own affidavit that day, one she not only read but helped compose—and signed herself. That day she, like Norma, filed more than six thousand pages of documents, including over two thousand affidavits from post-abortive women.

The shameful and irrational desire on the part of the courts to reach a decision in Roe and Doe with no evidence—and without even knowing if the women in whose names the cases were brought actually wanted abortions—was later exposed by the courage of these two women.

It was not easy for Norma and Sandra to stand up and tell the world the truth. After Roe, Norma was hailed by many as a national heroine of the same stature as Rosa Parks. She was lauded by pro-abortion groups. Norma gave up her life of acclaim, and accepted an onslaught of criticism when she stood up in 1997 and began to fight for what was right, at great personal cost.

The stories of Norma McCorvey and Sandra Cano are stories of redemption. As we carry on the fight to end abortion, we should take time to remember and to celebrate what they did for the rest of us as they fought to redeem themselves.