This essay is part of our collection “Advice for Donald Trump.” Read related pieces here.

The unfortunate death of Justice Antonin Scalia has highlighted a painful reality: Republican presidents have a terrible track record of nominating judicial conservatives to the Supreme Court. Like a small child who keeps reaching for a hot stove, they get burned again and again. For every Justice Scalia, Thomas, or Alito there is a Justice Stevens, Souter, or O’Connor. There are probably several reasons for this pattern, but one of the main ones is simply insufficient data on prospective nominees, which precludes an accurate prediction of how they’ll behave once they are appointed. Couple this with a trend noted by political scientists that once on the Court justices drift to the left ideologically, and you have a recipe for disappointment.

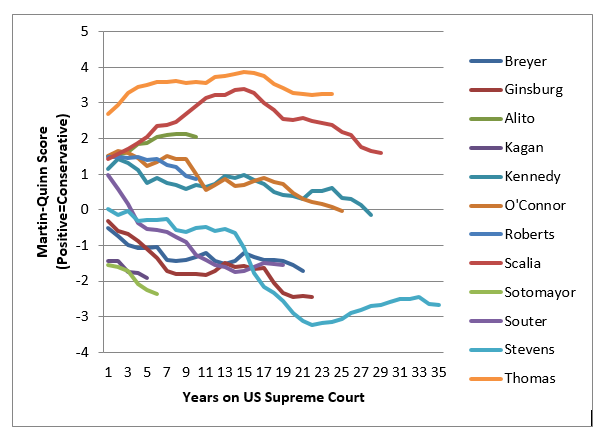

In the past forty years, Republican presidents have appointed eight justices—twice as many as Democratic presidents have. Yet only three of the eight currently are, or ended their tenure, as conservative as when they first took their seats. All four Democratic appointees are now (or were at the time of their deaths) more liberal than when they were appointed—at least according to the most common measure of such: Martin-Quinn Scores.

Judicial Liberals vs. Conservatives

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.The graph below shows the scores of these twelve appointees across their careers, starting with their first year on the Court:

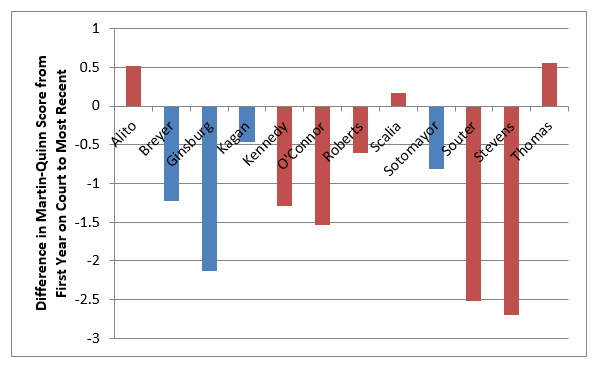

Another way to look at these changes is the raw change from their original score to their most recent score:

However one slices it, the story is the same: few justices can resist the lure of the liberal side.

Granted, Martin-Quinn Scores, which are based on the Spaeth Database, are not perfect. Technically the scores only measure voting patterns. And arguably these scores measure political ideology more than judicial ideology. While everyone has a pretty good sense of what it means to be politically conservative, in the judicial realm it’s a bit different.

Judicial conservatives can generally be divided into two camps: judicial minimalists and constitutional conservatives. Chief Justice Roberts is a good example of the former—someone who prefers distinguishing or narrowing precedent rather than overruling it. Even if the precedent is wrong, a minimalist believes a judge (based on common-law conceptions) moves the law only in piecemeal fashion—if at all—so as to maintain stability. A constitutional conservative is only worried about what the Constitution (or a statute) demands, with stare decisis having little or no weight. Justice Thomas is the model for the latter. Justice Scalia was a mix of a constitutional conservative and a judicial minimalist. Martin-Quinn Scores will not capture judicial conservatism as well as political conservatism, but the scores have some utility, and tell a story that most people find valid.

So why don’t Republican presidents appoint more Scalias and Thomases, and fewer Stevenses and Souters? The problem is empirical. The best predictor of how one will perform in a certain job is how one has previously performed in that very job. We are more confident that a surgeon will operate flawlessly when he has numerous flawless surgeries under his belt. We trust that a pilot will land the plane without a hitch because she has done so dozens of times before. This is obviously problematic for filling a position on the Supreme Court, since no other legal position, including judicial ones, are quite like being at the top of the pyramid.

That is because in the short term, there is nothing to check a Supreme Court justice other than a justice’s conscience and his or her theory of what the Constitution demands. In the long term, it is possible for a statute to override a statutory decision or for a constitutional amendment to override a constitutional decision. But the likelihood of the former is low, and of the latter practically nonexistent. Sure, political pressure can be brought to bear on the Court, and that may sometimes work. But the reality is that the independence of the Court, which was designed to shield it from political influence, also insulates it from effective external constraint.

So what is a conservative president to do? In the past, most presidents have deemed federal court of appeals experience as a prerequisite to being elevated to the Supreme Court. Only two of the twelve justices appointed in the past four decades did not serve in that position immediately prior to their nomination. And one of those, Justice O’Connor, was serving as a state court of appeals judge.

Unfortunately, experience as a federal court of appeals judge (or the state equivalent in Justice O’Connor’s case) is a poor indicator of what type of US Supreme Court justice one will be. And experience as an attorney (in Justice Kagan’s case) is an even poorer indicator. The reason is that appellate judges are hemmed in by Supreme Court precedent—a constraint not felt by those elevated to the Supreme Court. And attorneys are making arguments for their clients. So whether one had spent one year on a court of appeals or a dozen, the signal of how that person will be under none of these effective constraints is murky at best. The signal is downright opaque for someone who was a lawyer.

State Supreme Court Justices Show Their True Colors

Fortunately, though, there is one legal position in the United States that, under certain conditions, analogizes rather well to being a US Supreme Court justice: state supreme court justices. When it comes to interpreting their state’s constitution and statutes, no one looks over the shoulder of state supreme court justices: they are equivalent to a US Supreme Court justice interpreting the federal Constitution and statutes. If a state supreme court justice acts like a Justice Thomas or Justice Scalia when interpreting her state constitution or statutes, she will almost certainly do so if put on the US Supreme Court. Thus, their true colors come out since they—under certain conditions—have practically no more constraint than their federal counterparts.

But the caveat of “certain conditions” is important, since not all state judiciaries operate the same way. For our purposes, there are four types of state supreme courts:

1. Appointment and confirmation with either life tenure or tenure until a certain age

2. Appointment and confirmation with periodic retention elections

3. Appointment and confirmation with periodic contested elections (partisan or non-partisan)

4. An initial contested election with periodic contested elections (partisan or non-partisan)

The first two, especially the first, are the most similar to what US Supreme Court justices experience. After they are put on the bench, there is no direct political check on their performance, and so they don’t need to worry about the next election as they make decisions. Periodic retention elections have so seldom resulted in a state supreme court justice being removed from office—six in the past fifty years, by my count, and all in just two states—that they are a minor constraint at best.

But for justices who face contested elections and are thus constrained by the people, it is uncertain how much of their decision-making reflects their true behavior and how much of it is an attempt to keep their job. In fact, political scientists have found that on some hot-button issues, state supreme court justices in states with contested elections will move their votes closer to the views of the majority of the state’s population when reelection time draws near. Thus, justices from states in categories one and two will provide much clearer signals regarding what a particular justice would act like if placed on the US Supreme Court, while those in categories three and four provide a far muddier signal.

For over a half century, presidents have not looked to sitting state supreme court justices to fill vacancies on the US Supreme Court (though Donald Trump’s supposed short list did include several). This pattern of ignoring state supreme court justices may stem from the decreased prestige of the position compared to federal judgeships. While state supreme courts were once stocked with legal luminaries such as Cardozo and Holmes, generally lesser lights have filled those seats since the 1930s. But that has begun to change. In recent years, individuals with credentials as impressive as those of anyone on the federal bench have been appointed to state supreme court positions, and some of these are constitutional conservatives.

In the hierarchy of legal positions that send clear signals about behavior in a potential Supreme Court justice, the job of law professor comes in a distant second. Law professors write about what they want, and whatever constraint that does exist tends to push them in a liberal direction since that is the orthodoxy of the legal academy (and thus of those who make the hiring and tenure decisions). Hence, a law professor who looks like a Justice Scalia or Thomas in his scholarship will probably stay the course when on the bench.

Next come federal circuit court of appeals judges. Besides the aforementioned precedent constraint that muddies the waters, federal circuit judges know that almost all Supreme Court Justices in modern history have come from their ranks. Many circuit judges have, in the backs of their minds, the possibility they will get the call to the high court. This can also act as a restraint that masks their true colors, since their time on the bench can be seen as one extended job interview. (By contrast, state supreme court justices have no expectation of elevation to the US Supreme Court, so—at least at the moment—they are not as prone to this tendency).

Finally, in fourth place are appellate lawyers and elected officials, such as state attorneys general, US senators, and elected state supreme court justices. The desire to be reelected may unduly influence such figures and change the way they present themselves. Still, potential candidates in these categories can send clearer signals by going out of their way to take positions that either cut against their political interests (if they’re in a liberal state, for instance) or are unnecessary and thus show their true beliefs (such as speeches or legal scholarship).

Other types of legal positions, particularly non-appellate lawyers and trial judges, are just too much of a leap to be considered for direct elevation to the Supreme Court. They require different skill sets.

So the next Republican president should first look to state supreme court justices. It’s simply a matter of more accurate information. While there may be potentially excellent candidates among these other legal positions, their track records are just harder to read than that of a state supreme justice from the right state. From one of these second-best legal positions we could get another Justice Thomas or Scalia. But given the track record, we could just as easily get a Justice Stevens or Souter.

And given the current state of the country, of our government, and of a currently evenly divided Supreme Court, it’s not certain that our republic can handle another such mistake of judgment.