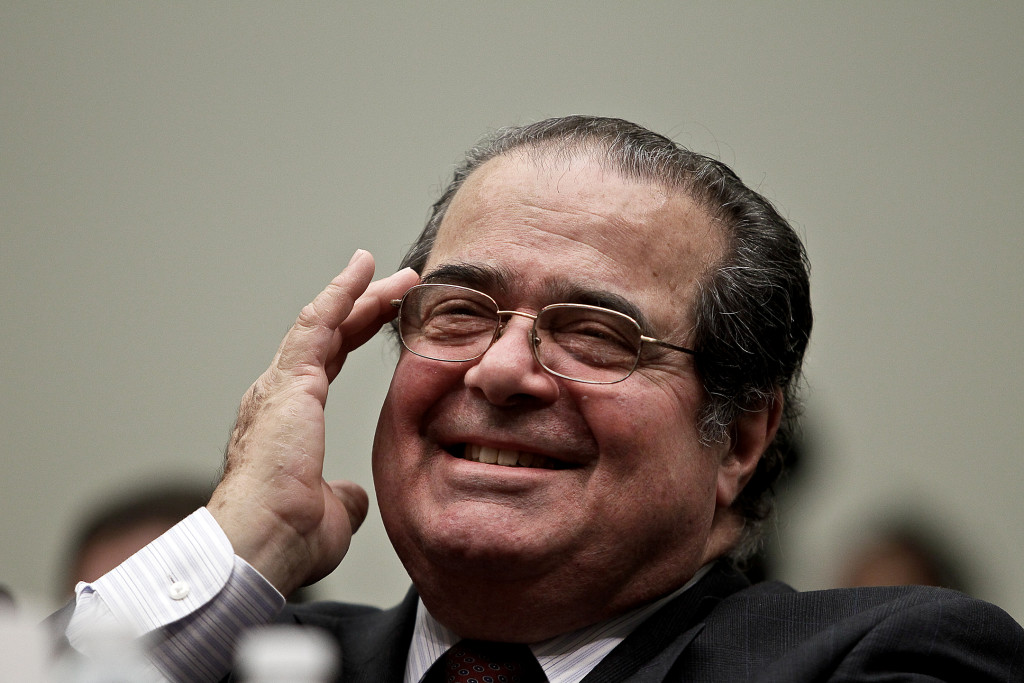

Like many Americans, I was shocked and saddened at the news that broke on the afternoon of Saturday, February 13, that Justice Antonin Scalia had died in his sleep at a hunting lodge in Texas. He left a widow, nine children, and thirty-six grandchildren. Along with Justice Scalia himself, these bereaved family members should be in our thoughts and prayers. He also left behind many friends and admirers whose lives he touched, and countless students whose minds he enlightened.

By “students,” I do not mean only those who took his classes when he was a law professor, nor do I limit myself to the scores of young lawyers who served as his clerks during his few years on the DC Circuit Court of Appeals and his thirty years of service on the Supreme Court. Many, many more students of the Constitution, both professional academic scholars and amateur citizen-students of the Constitution, were the beneficiaries of his teaching.

I myself can claim no personal relationship with Justice Scalia, although I met him a couple of times and heard him speak on several occasions. But I certainly was his student. In 1986, when he was appointed to the Supreme Court, I was just beginning my career as a teacher of constitutional law. I quickly learned that Antonin Scalia was a man who bore watching, who commanded respect, who could always be counted on to tell you just what he thought and to make a compelling case that you should think it too.

Scalia’s Lessons: The Rule of Law, Self-Government, and the Virtue of Persistence

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.Justice Scalia was justly celebrated for his gifts as a writer of judicial opinions—for his clarity, his often barbed wit, and his forcefulness. But he was not merely clever, and he was never superficial. That funny, memorable, eloquent voice of his was deployed in the service of durable truths about our law and politics that only a deeply learned student of our constitutional order could express with such charming ease. As my own teaching and scholarship deepened over time, I found I could confidently disagree with Justice Scalia about a few things—but that confidence was hard-earned, because he was so good at what he did, so perceptive and persuasive about the meaning of the law. Even for that hard-won privilege of occasional disagreement, I owe Justice Scalia a great deal, and so do my own students. Whenever we have a Scalia opinion to read and study together, we know we are in for a treat, and for a lesson.

So what was it that Scalia taught so well, through the medium of the judicial opinion? First, that the integrity of the rule of law itself depended on the outcome of the struggle between two schools of thought on interpreting the Constitution—the “living Constitution” approach and its adversary, which has come to be called “originalism.” More than any other justice on the Court in over a century, Antonin Scalia was responsible for advancing the view that the Constitution means what it says, says what it means, and does not “evolve” to say new things it never said before. If ours is to be a government of laws and not of men, then our highest law especially must be read in a way that respects the language in which it was written, and the meaning that objectively attaches to those words in the minds of those who wrote it and those for whom it was written. Professors might play whatever word games they like, but for a judge, anything less than total commitment to such decision-making integrity was a betrayal of one’s oath of office.

Second—and relatedly—Scalia taught that our self-government as a people was at stake in this struggle between competing ways of reading the Constitution. For the “living Constitution” approach means that five justices are entitled to amend the Constitution itself, a power that the document reserves to the people, working through representative institutions that are answerable to them at elections. Hence, judicial rulings that do violence to the Constitution’s original meaning by changing it to say something no one ever intended or understood should be viewed as robbing the people of their right of self-government under laws of their own making.

Government by judiciary, so understood, is usurpation and tyranny. It is an assault on constitutional republicanism and on the integrity of law. To the extent that the people become inured to such usurpation and tyranny, our political culture is deeply wounded, and the upright posture of republican citizens is bent into bowing, forelock-tugging obeisance to our robed rulers on the Supreme Court bench.

A third and final lesson taught by Justice Scalia is the virtue of persistence in the face of repeated frustration and disappointment. Such persistence is a manifestation of courage, a virtue to which Scalia paid tribute in a 2011 speech to the young military cadets at New York’s Xavier High School (from which he had graduated in 1953). After quoting C.S. Lewis’s line that courage is “the form of every virtue at the testing point,” Scalia went on to say that “the long fight we are in for,” each and every one of us, is “putting things right in the world God has created, starting with ourselves.” This is seriously hard work, requiring steady practice and stick-to-it-iveness if we are to make any headway at all; it demands that we must not flag or lay down our burden at those times when we seem to be making no headway.

Scalia’s Steady Opposition to Roe

Scalia never flagged, and from his arrival on the Supreme Court in 1986, he stood out for his ability to stiffen the spines of others too. Nowhere was this more evident than on the abortion issue. In 1973, Roe v. Wade had been decided 7 to 2, and the dissents of Justices William Rehnquist and Byron White were memorable for their outrage at this violence to the Constitution. When Ronald Reagan took office in 1981, there were high hopes among the pro-life community that he would appoint justices to the Supreme Court who would right the wrong of Roe v. Wade, which the Republican platform had condemned. In his first year, he appointed Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, and two years later we knew that Reagan had fallen short of the mark on that appointment. In a case from Ohio in 1983, O’Connor criticized the “trimester” framework of Roe as a mass of contradictions, but she would not grasp the nettle and say that the Court had been simply wrong ten years before.

In 1986, Chief Justice Warren Burger, part of the Roe majority, retired, after which President Reagan nominated Justice Rehnquist to be chief justice and Judge Scalia to fill the associate justice seat that Rehnquist would vacate. Just before he retired, Burger indicated, in a Pennsylvania abortion case, that after thirteen years’ experience with the distortions Roe had introduced into our law, he was ready to consider overruling it. In that same case, Justice White (joined by Rehnquist) renewed his objection to the “illegitimacy” of what the Court had done in Roe. Unfortunately, Justice O’Connor (also dissenting and also joined by Rehnquist) persisted in her bizarre project of criticizing everything about Roe except the grievous wrong it did to the Constitution.

Then Justice Scalia arrived on the Court. In 1989, in a case from Missouri that was his first opportunity to grapple as a Supreme Court justice with the legacy of Roe, the Court upheld a number of mild restrictions on access to abortion. Perhaps because he needed O’Connor’s vote for that result (and the vote of the new Justice Anthony Kennedy, we can now surmise based on later events), Chief Justice Rehnquist held for the Court that it was not necessary to reexamine Roe in order to uphold Missouri’s restrictions, and Justice White went silently along with that opinion.

But Justice Scalia was having none of it. He wrote, in a separate concurrence:

The outcome of today’s case will doubtless be heralded as a triumph of judicial statesmanship. It is not that, unless it is statesmanlike needlessly to prolong this Court’s self-awarded sovereignty over a field where it has little proper business since the answers to most of the cruel questions posed are political and not juridical—a sovereignty which therefore quite properly, but to the great damage of the Court, makes it the object of the sort of organized public pressure that political institutions in a democracy ought to receive.

In other words, when you’re just wrong, stop being wrong, turn around, and get it right. And here, in Scalia’s first opinion in an abortion case, was his clear and oft-repeated theme: because the Constitution does not support a judicial invention of the abortion right, such an invention distorts our political life by corrupting the public’s understanding of what courts of law properly do. People begin to think of the Supreme Court as just another kind of political institution, subject to political pressures, though just out of reach of their electoral control except when a vacancy on the bench brings an opportunity within reach. Nothing could begin to heal these self-inflicted wounds on the Court’s integrity but a firm resolve to overturn Roe.

The Effect of Scalia’s Persistence

The effect of Scalia’s appointment to the Court became vividly evident in Planned Parenthood v. Casey in 1992. Once again, the Court mostly upheld a set of mild restrictions on access to abortion, this time legislated by Pennsylvania. Indeed, there were seven votes to uphold most of the legislation, and a “compromise” opinion as before might have been crafted to attempt to speak for them all. But now four of those seven justices declared themselves ready to wipe the slate clean by overturning Roe. Chief Justice Rehnquist said so explicitly and was joined by White, Scalia, and the recently appointed Justice Clarence Thomas. And Scalia wrote one of his most outstanding opinions in Casey, which was also joined by the other three. It was undoubtedly the persuasive force of Scalia’s persistent arguments, as well as the arrival of Justice Thomas as a stalwart ally, that brought Rehnquist and White back to the firmly constitutional position that Roe must go.

Tragically, Casey preserved the essentially unlimited abortion right, thanks to Justices O’Connor, Kennedy, and David Souter—all appointees of the party with the pro-life plank in its platform. But their hand had been forced by Scalia’s persistence, and their Casey opinion has gone down in history—alongside Roe itself—as one of the most shamefully wrong opinions ever published. Wrong at every turn about the Constitution, wrong about when precedents should and should not be followed, wrong about the Court’s role in our system of government, and wrong about the people’s right to govern themselves on society’s great moral questions—Casey is a curse against the rule of law, as well as a great crime against the fundamental right to life. Even pro-choice scholars seem to understand it as an embarrassment best left unscrutinized.

Justice Scalia kept at it for the next two and a half decades, banging on indefatigably about the distortions and injustices generated by Roe and Casey—in themselves and in later abortion cases, in their effect on other areas of law like the freedom of speech (see his opinions in the sidewalk-counseling cases), and in the encouragement they gave the “living Constitution” justices to invent still more new rights that cannot be squared with any plausible reading of the text, such as the “right” to same-sex “marriage.”

Was Justice Scalia strengthened, and enabled to persist in this long struggle against the abortion license and all its unholy fruits by his manifest faith as a Catholic, and by an almost certain but publicly unstated commitment to the moral status of the unborn? I expect so. But he not only never thought it appropriate, he was convinced it was inappropriate, to bring such personal devotion into his judicial decision-making and opinion-writing. Bringing their political and moral commitments to bear on their legal judgments—that was for his opposite numbers on the Court, not for Justice Scalia. He instead gave us plain, passionate, compelling instruction in how to argue the constitutional case for dismantling the abortion license constitutionally—if necessary, “disassembled doorjamb by doorjamb,” as he put it in 1989—but one day swept aside in a restoration of lawful government, constitutional integrity, and the people’s right to protect all life as we see fit, unhindered by judicial elites who claim to know better than we do.

The rule of law, republican self-government, and the virtue of courageous persistence in a good cause. Not a bad teaching for a man to leave his many students.