To discover more excellent reads and cinema selections, don’t miss our Isolation Bookshelf collection.

Long before I took up science fiction—the subject of my column last week—I was an enthusiast for well-crafted historical fiction, and I still am. Like science fiction, historical fiction is “escapist” writing, but of a wholly different kind, involving a quite different form of imagination. The historical novelist brings us to a familiar or recognizable past, to inhabit real events, often encountering famous historical figures, alongside fictional characters whose lives the writer has woven into real history.

Naturally such novels take considerable liberties with history—to the consternation of some humorless historians—not only introducing invented persons in the scenes of actual events, but often deploying the real persons they encounter as significant characters, sometimes even as the protagonists, with motives, speeches, and actions entirely imagined by the author. Thus not every novel set in the near or distant past is necessarily in the historical fiction genre: Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, for instance, written decades after the period in which it is set, involves no encounter by its characters with historic personages or actual events, and so does not belong in the genre I am describing. It is simply a novel, and a fine one.

One of the demands of the historical fiction genre, then, is the achievement of verisimilitude—a very different thing from the veracity demanded of the historian. We must believe the actual historical figures in these novels could have said or done the things we read, and that the fictional characters likewise could have been present at the real events we see them involved in.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.One such novel I enjoyed years ago is Count Belisarius (1938), by Robert Graves. Better known for I, Claudius, Graves was a poet, a memoirist, and the author of many books of various kinds. Just as I, Claudius drew heavily on the Roman history of Suetonius, so Count Belisarius, the story of a real general under the Byzantine emperor Justinian, relies on the history of Procopius. The story is told in the first person by a slave of Belisarius’s wife Antonina, and follows the exploits of our sixth-century protagonist from Constantinople to Persia, to Rome, to North Africa. For me, as I expect is true for many readers, this is a place and time wholly foreign, so there is something truly fascinating about being placed in this early Christian culture, with the inheritance of Rome having passed to the eastern empire, while “barbarian” peoples range across western Europe.

“Owen Glendower, lord of Glyndyfrdwy and Cynllaith, and master of most of North Wales, came south that summer into central Wales, his raiding parties materialising like shapes of flashing, thundery sunlight out of the rains and mists of the hills . . .” Thus writes Edith Pargeter in A Bloody Field by Shrewsbury (1972), a novel set at the beginning of the fifteenth century, featuring the “three Henries”—Henry Bolingbroke who becomes Henry IV, his son Prince Hal who succeeds him as Henry V, and Henry Percy, known as Hotspur. These are all familiar figures from Shakespeare, so it takes a bold writer to limn their portraits anew and do so as memorably as Pargeter does. Pargeter also wrote, as “Ellis Peters,” the excellent Brother Cadfael mysteries, but her historical fiction is even better. (I have yet to read her massive Brothers of Gwynedd Quartet, but I intend to.)

Three of my favorite writers in this genre wrote (or in one case are still writing) long cycles of novels following certain characters. Patrick O’Brian’s twenty novels featuring John Aubrey, Royal Navy captain, and Stephen Maturin, ship’s surgeon, are a wholly absorbing excursion into the world of naval warfare during the Napoleonic period, and a remarkable portrait of a friendship over many years. Start with Master and Commander (1970), whose plot bears no resemblance to that of the movie by the same title, which is actually based on the tenth book in the series—from which the film takes its subtitle—The Far Side of the World.

A worthy successor to the late O’Brian is Allan Mallinson, a retired British army officer who has published thirteen novels set mostly in the immediate post-Napoleonic period, featuring Matthew Hervey, an officer of a light dragoons regiment. Mallinson does for the cavalry what O’Brian did for the navy: give the reader a true “you are there” feeling for what life was like for officers and men serving in the wars of their time. The Hervey series begins with A Close Run Thing (1999), which takes the reader onto the battlefield of Waterloo. This August, Mallinson will publish the fourteenth Hervey novel, The Tigress of Mysore, set in India in the early 1830s.

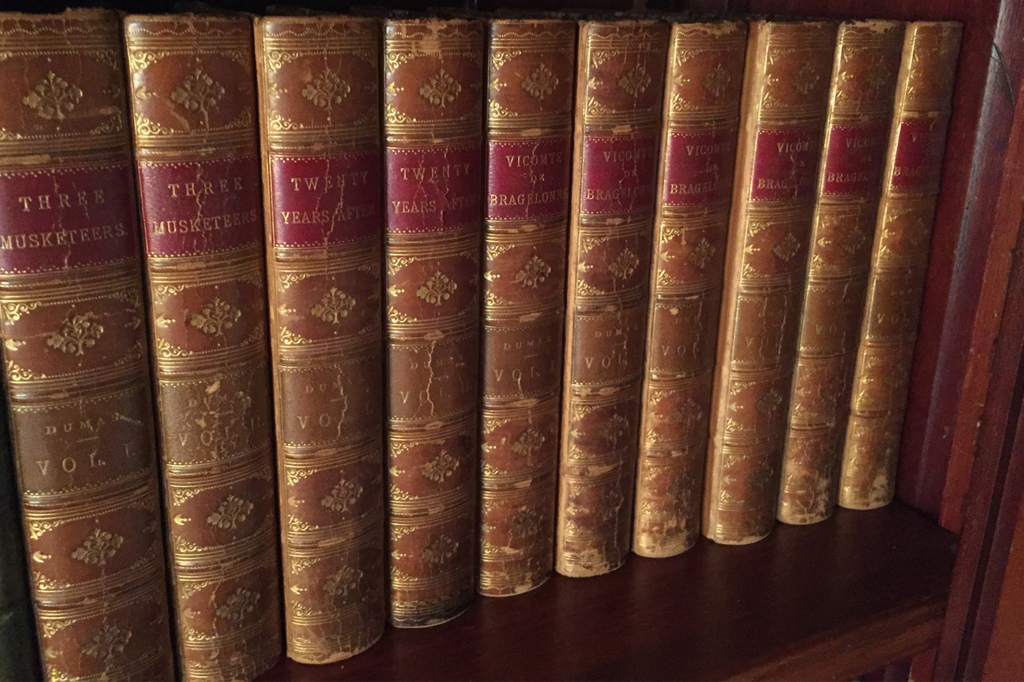

I’ve saved the best for last. My introduction to the high adventure of the best historical fiction came when I discovered many years ago, in my grandmother’s house, the D’Artagnan novels of Alexandre Dumas, published from 1844 to 1850. Everyone knows—even if only from two cheesy 1970s movies—The Three Musketeers. Far fewer know of the sequels, Twenty Years After—set, well, you know when—and The Vicomte de Bragelonne, set ten more years later. The set I read, and now own (pictured above), amounts to ten volumes, totaling about 4,000 pages. I prefer this old translation to the modern ones available today, but happily, to save wear and tear on my 1890s Little, Brown edition, I’m now able to reread them on a tablet with a Google Books scan of the very same volumes, which you can find online beginning with Volume I of The Three Musketeers.

From the intrigues of Richelieu, to the execution of Britain’s Charles I, to the coming of age of Louis XIV—and weaving into the six volumes of Bragelonne the legend of “the Man in the Iron Mask,” among other subplots—the D’Artagnan novels are unmatched in historical fiction. Robert Louis Stevenson, no slouch in this genre himself, wrote in 1887, “Perhaps my dearest and best friend outside of Shakespeare is D’Artagnan—the elderly D’Artagnan of The Vicomte de Bragelonne. I know not a more human soul, nor, in his way, a finer; I shall be very sorry for the man who is so much of a pedant in morals that he cannot learn from the Captain of Musketeers.”

I would go further. There is a great deal to be learned about the virtues and vices by following the long and eventful lives of D’Artagnan, Athos, Porthos, and Aramis. And isn’t this finally what good novels of any kind do for us—present the fullness of human characters for our consideration, so that we may reflect on our own characters?