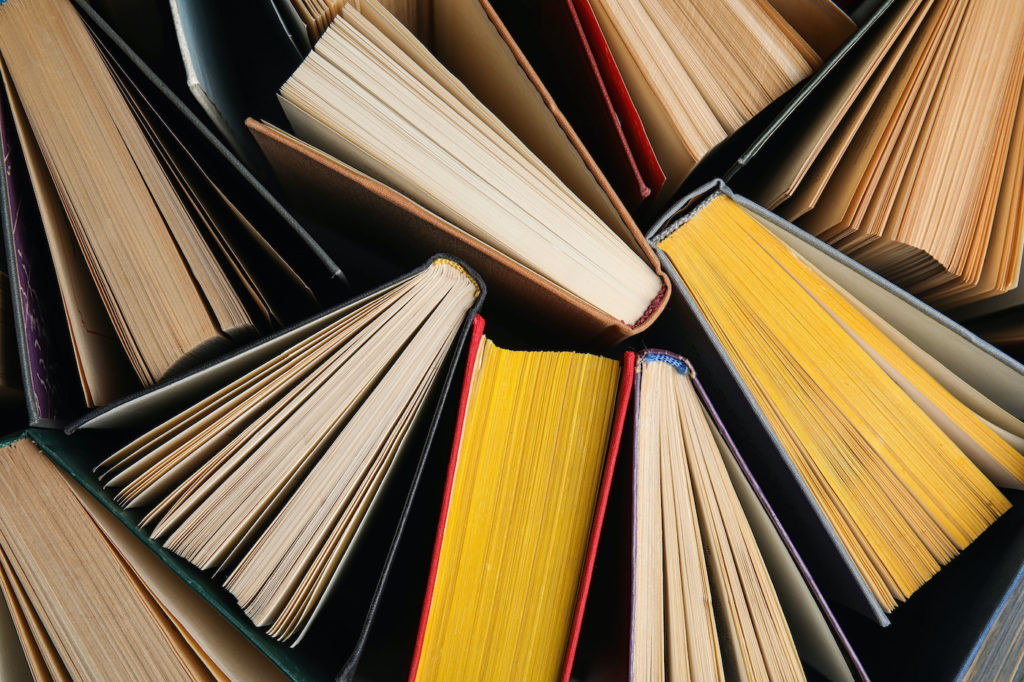

To discover more excellent reads and cinema selections, don’t miss our Isolation Bookshelf collection.

I am hardly alone in occasionally feeling that we are living these days through scenes from a science fiction novel or film. One friend said to me weeks ago that our cities’ nearly deserted streets had an On the Beach feel about them, referring to Nevil Shute’s 1957 post-apocalyptic novel that was made into a movie two years later. I thought of that when I went down an empty interstate on a weekday morning at a time that should have been rush hour. When a small herd of deer crossed our yard just a few feet from the front door at noontime one day this week—creatures that usually venture into our neighborhood yards only at night—I was struck again by what a strange time this is.

Science fiction at its best places its characters in extreme situations and explores the human capacity to adapt, survive, and display all the best—and worst—characteristics of the species. Obviously it is not the only form of fiction that can do this, but with its imagined worlds, futures, and peoples, science fiction is capable of pushing the boundaries of the humanly possible and revealing something about ourselves.

I read a great deal of science fiction from my college days through my twenties, with a strong preference for the landmark fiction of the genre’s “golden age” of the 1940s to the early 1960s, when editors like John W. Campbell fostered the careers of many notable writers. I don’t read much “sf” (please, not “sci fi”) any more, and I wonder sometimes who does still read writers like Theodore Sturgeon, A. E. Van Vogt, C. M. Kornbluth, Poul Anderson, Frederik Pohl, Fritz Leiber, Algis Budrys, and Cordwainer Smith. But I’m not sorry I went through that spell of enthusiasm.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.Many of the sf books I once owned I have shed in successive moves, but there are a few books I’ve kept because they’ve borne rereading. Frank Herbert’s Dune (1965)—soon to be made into a film again—is an obvious choice, an astonishing work of imagining a whole universe with its own history, culture, economy, religions, and politics. When a young man on the run finds himself set down among a desert people whom he comes to lead as a messianic figure, the reverberations affect a whole interplanetary society. (The sequels, for what it’s worth, don’t measure up.)

Turning to less well-known sf classics, I would recommend the two greatest novels of Alfred Bester. His first book, The Demolished Man, won the very first Hugo Award for best science fiction novel of 1953. It depicts a future in which telepathy is common (though not a universal gift), and examines how a man would attempt to get away with murder when the police in particular rely on mind-reading. Bester’s third novel, The Stars My Destination (1956), is a revenge tale, an hommage to Dumas’s The Count of Monte Cristo, set in a society in which human teleportation has been achieved—the instantaneous relocation of a person by the power of his thoughts alone. Bester’s writing was positively pyrotechnic, and both books move the reader at a breakneck pace, with none of the “science” of either telepathy or teleportation, or the details of how society is changed by these evolutions in human ability, belabored with long-winded exposition. The author counts on providing just enough of such context for his readers that they are compelled to join him in imagining these worlds for themselves, while the tale races on.

The best post-apocalypse novel I know is Walter M. Miller, Jr.’s A Canticle for Leibowitz (1959). As I described it in 2014, the novel “imagines a very long future in which, after the utter collapse of our present civilization, scientific knowledge and literate culture are preserved by a Catholic monastery.” Miller places several generations of abbots and monks in the Utah desert at the center of his story, which takes us from the blasted ruins of our own society, with the cryptic “relics” it left behind, to the rebuilding of a new and very rough civilization that recapitulates many of our most grievous errors.

I once went through a phase of reading everything I could find by Robert A. Heinlein, from his “juveniles” to his more mature works. Neither his libertarianism nor his sexual libertinism particularly appealed to me, but the man knew how to write “hard sf,” heavy on the futuristic science, and he could plot an exciting novel like few others. A good candidate for his best book is The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress (1966), in which the earth’s moon is a penal colony that develops its own polyandrous and polyamorous marriage culture, owing to the low ratio of women to men (as one would expect in a prison population). But that’s just social background for the story of a revolution, when the people of Luna decide to break away from Earth’s government as an independent republic. Oh, and for good measure there’s a computer that achieves its own consciousness.

We live in an improbable time. Yes, there are people who have warned us about global pandemics for years. But improbable, even outlandish, is just how life feels right now. What can human beings endure? How can they adapt to radical changes in their environment and in themselves? How will their choices reshape their society? As I said, science fiction at its best invites us to consider such questions at the extremes of human experience.