Sometime in 2007, when Robert P. George and I had agreed to publish Embryo: A Defense of Human Life with Doubleday, our editor, Adam Bellow, got in touch to request a change to the beginning of the book. I no longer have the correspondence but the substance of the complaint was that our opening pages were . . . dry. I am confident that the complaint was just, and can guess that we opened with some abstract claims about justice. That is an occupational hazard for both of us.

In search of something with a bit more zing, I was astonished to come upon the story of Noah Benton Markham. Noah had been among 1,400 cryopreserved embryos whose lives were threatened by Hurricane Katrina, and he was among the lucky ones to be rescued by police officers using flat-bottomed boats. He was born sixteen months after Katrina’s devastation, his name an obvious tribute to his unusual history.

We opened Embryo (later updated in a second edition from the Witherspoon Institute) with Noah’s story in order to make a simple, but essential, point: it was Noah who was rescued by those police officers (combined forces from Illinois and Louisiana). It is true that Noah existed at that time in the very earliest stages of human life, as an embryo; and true also that he existed in a state of suspended animation, cryopreserved in anticipation of the possibility of eventual implantation in his mother’s womb. But, as we noted,

[I]f those officers had never made it to Noah’s hospital, or if they had abandoned those canisters of liquid nitrogen, there can be little doubt that the toll of Katrina would have been fourteen hundred human beings higher than it already was, and Noah, sadly, would have perished before having the opportunity to meet his loving family.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.

The story of Noah was recalled to my mind in recent days by the announcement that the Alabama Supreme Court had ruled that cryopreserved—frozen—human embryos are to be considered “unborn children” under the 1872 “Wrongful Death of a Minor Act” that “allows parents of a deceased child to recover punitive damages for their child’s death.” That act contained no exception for in vitro embryonic human beings, and the Court thus ruled that the “Wrongful Death of a Minor Act applies to all unborn children, regardless of their location.”

There is no doubt that the ruling opens up many legal and policy difficulties that remain to be addressed. But those final four words of the Court’s opening paragraph, “regardless of their location,” get to the heart of the most important biological and moral issues regarding in vitro embryos: location does not matter either to the humanity or to the moral status of those embryos. These were points that Professor George and I argued at length in Embryo, and it is worth returning to those arguments briefly, since the Alabama Court’s judgment is being met at many turns with incredulity: how can a cryopreserved in vitro embryo actually be a human being, with a claim to the same kind of respectful treatment to which you, the reader, or I, the author of this essay, are entitled?

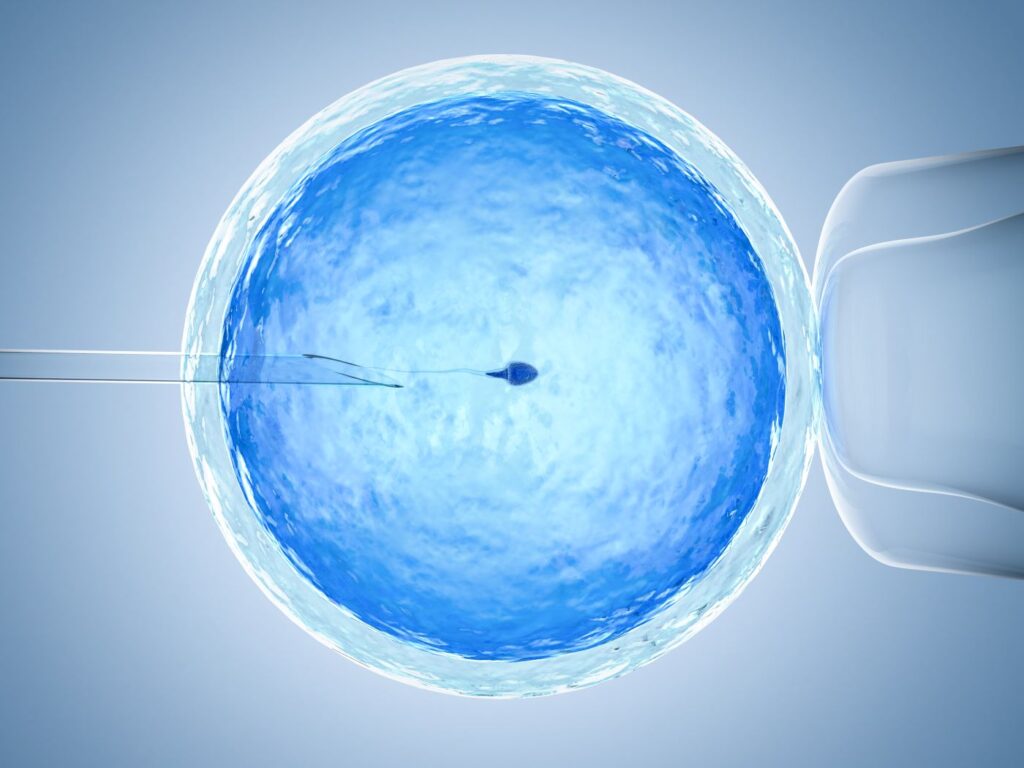

It is necessary to begin, of course, with the question of the in vivo embryo, the result, after sexual intercourse, of the fertilization of an oocyte by a sperm cell. Is that single-celled entity, the zygote, a human being? As we noted in Embryo, and many times since, the verdict of every embryology and developmental biology textbook that we consulted is affirmative. As Moore and Persaud write in The Developing Human, “This highly specialized totipotent cell marked the beginning of each of us as a distinct individual.”

The reason for the uniform convergence by experts in biology is quite straightforward: at fertilization, two gametic cells, the sperm and the oocyte, cease to exist, and a new single-celled organism comes into being. This zygotic individual is biologically distinct from his or her parents and is possessed of both the genetic and epigenetic starting points necessary to be the primary agent of its own growth and development to the next stages of human life.

Of course, the zygote, like any human being, requires that certain other conditions be met in order for that growth and development to be possible. Deprived of hospitable environmental conditions, nutrition, and the love and care of other human beings, no human being will flourish, and if the circumstances are sufficiently hostile, they will die. The embryo is no different: in the absence of a uterine home, embryos will eventually arrest their growth or, as in an ectopic pregnancy, put both their own life and the life of their mother at risk.

Certainly, a petri dish is an inhospitable environment for continued growth; nor does the technology currently exist to sustain the embryo’s life for very long outside the mother. Yet there is no question, biologically, that the embryo that, as a result of in vitro fertilization, exists in a petri dish is, if implanted and gestated, the same human being who will eventually come to term, then grow as an infant, adolescent, and beyond. No biological change in the embryo takes place at implantation, only a change in “location.”

Indeed, it seems clear that in time there will be artificial wombs, in which artificially conceived embryos can receive something like the nutrition and support they would be given in utero, such that they can be gestated to the point of viability. The biological continuity, the lack of any real or substantial change, would be visibly apparent to all. Just as it was Noah who was rescued, so it would be James, or Mary, who would be nurtured from the zygotic state to the point where he or she would be capable of life outside the womb.

Does cryopreservation make any difference to the issue? It is hard to see how it could: the embryo that is conceived in vitro is a distinct and individual human being; its metabolism is then radically slowed through submersion in liquid hydrogen, and it is left undisturbed for some period of time, perhaps years, before being resuscitated at normal temperature. There is now an embryo ready for implantation. Is it a different embryo from the one that was frozen? That would be quite a trick! The newly resuscitated embryo has precisely the same genetic profile, the same physical makeup, and occupies the same physical space as the embryo that was frozen. How could it be a different entity?

But then, if the resuscitated embryo is the same human being as the embryo before freezing, then the frozen embryo is that very same human being as well. The human being does not cease to exist or die, only to come back to life at room temperature. Such gaps in an organism’s existence are unknown to science.

Change a human being’s location, and you will often change what is needed for that human being’s continued survival. A human being underwater for an extended time needs oxygen tanks; a human being in the Arctic needs a heater; a human being in space requires a tremendous amount of technological assistance to stay alive. The embryo is no different: removed to, or created in, a petri dish, the embryo must either be implanted, grow in vitro until growth is no longer possible, or be frozen in order to stave off death. But none of that makes any difference to what it is: it is an unborn child, regardless of location.

Location is simply one more of those many factors that make no difference where the most foundational moral principles are concerned.

And if we think but a bit more on the matter, it is clear that such changes of location can make no difference to the embryo’s moral status either. The moral position defended in Embryo is one founded on a recognition of the radical equality of all human beings. You and I, after all, have a right to respectful treatment, including a right not to be killed at will, that does not vary in consequence of the many differences that exist between us—differences of age, intelligence, awareness, status, or appearance. What can such an equality of rights be founded on except the one thing we do have equally in common: our humanity?

Location is simply one more of those many factors that make no difference where the most foundational moral principles are concerned. The human embryo is a human being, whether in utero, undergoing cell division in vitro, or temporarily (or permanently) in frozen stasis in a “nursery,” as the Alabama Supreme Court tellingly, but somewhat ironically, calls it.

The consequences for IVF as currently practiced are clear enough. Leaving aside moral concerns with the process itself, as a form of baby making, it is clear that the IVF industry in the U.S. has been in the business of creating perhaps millions of embryonic human beings that will never be given the chance to grow and develop their human potential, but will instead be frozen or discarded. As one medical website put it in reporting on the Alabama ruling: “Embryo loss is integral to IVF.”

That is the plain truth, which needs to be acknowledged in conjunction with the plain truth affirmed by the Alabama Court, though denied by many: those embryos are “unborn children, regardless of their location.”

Image by phonlamaiphoto and licensed via Adobe Stock.