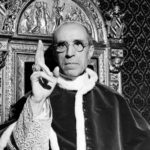

On October 31st, the Wall Street Journal published an article entitled “Vatican’s Silence on Holocaust Was Shaped by Anti-Semitism and Caution, Archives Show,” which discussed the recently released Vatican archives on the pontificate of Pope Pius XII (1939–1958) and a related conference at the Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome. Pius, of course, is the wartime pope sometimes accused of turning a blind eye to Nazi atrocities. At this conference, Jewish and Catholic scholars gathered to consider the Holy See’s wartime actions in light of the new archives and work to strengthen Jewish–Catholic relations.

As German author Michael Hesseman wrote, the meeting was “a rather one-sided selection of speakers,” favoring those who questioned the pope’s leadership. Nonetheless, those who carefully watched the proceedings should have noted a strong shift in favor of the wartime pontiff’s reputation. The Wall Street Journal piece, however, seems to have missed the historic developments, reporting instead on longstanding (and now largely debunked) criticisms of the pope.

One of the biggest developments to emerge from the conference is that the Vatican under Pope Francis, far from slackening its support of Pius XII, has actually increased it. This was exemplified by Cardinal Secretary of State Pietro Parolin’s opening address. Cardinal Parolin pointed to the newly declassified documents and said they reveal an image of Pope Pius XII “that is much different from what is generally known.” Specifically, Cardinal Parolin highlighted Pius XII’s vigorous condemnation of anti-Semitism in 1916, long before he became pope. The Cardinal also referred to “scientific dishonesty among historians hostile to Pius,” a reference probably directed to some of those in attendance.

Thanks to the newly opened archives, Cardinal Parolin explained, it has become “evident that the Pope followed both the path of diplomacy and that of undeclared resistance.” He went on to explain: “This decision was not apathetic and lacking in action,” but instead, entailed significant risks for anyone involved in them. That, as papal defenders have long maintained, is why Pope Pius rarely, if ever, composed written directives. Possessing or circulating them would have instantly condemned anyone found to have them in their possession.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.Sister Grazia Loparco, a professor of church history at Rome’s Pontifical Faculty of Educational Sciences “Auxilium,” told the conference attendees that for precisely this reason it is unlikely Pope Pius XII wrote out orders to hide Jews. “However,” Sister Loparco explained, “that he was aware and that he supported” Catholic rescue is “very clear,” since the cloistered religious communities had to be given permission to carry out this work. She further explained that oral communication in the Church hierarchy “worked very well in Rome.” Every morning, a priest from the Vatican or the Diocese of Rome visited each women’s religious house in order to celebrate Mass, making it “very easy” to pass along information.

Thanks to the newly opened archives, Cardinal Parolin explained, it has become “evident that the Pope followed both the path of diplomacy and that of undeclared resistance.”

One of the current charges against Pius XII is that he protected only those Jews who were baptized into the Catholic Church. Suzanne Brown-Fleming, Director of International Academic Programs at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, for instance, spoke of “overwhelming support for Catholics who fell under the racial laws.” David Kertzer, author of the controversial book The Pope at War, claimed, “The Vatican was only trying to save baptized Jews.” As the conference established, however, the Vatican archives tell a different story.

University historian Father Hubert Wolf from Münster, leader of the largest research team studying the new archives, also used to think that. A few years ago, he released an initial report highly critical of Pius XII. Since then, however, his team went on to evaluate about 1,700 requests for help from persecuted Jews to the Vatican. They discovered that ninety percent of the requests were processed, and ten percent were submitted personally to the pope. The pontiff ordered concrete help in every case. These newer findings caused Wolf to walk back his earlier criticism. The archives establish that when it came to assistance from the Vatican, there was “no fundamental difference between Jews and ‘baptized Jews.’” Wolf presented at the conference in front of a projection that said that very thing.

Astoundingly, the Wall Street Journal article barely mentioned Wolf. Even worse, it reported: “The Vatican gave priority to helping people of Jewish descent who were baptized Catholics”—precisely what Wolf and his team of archival researchers have since disproved.

The piece gave some attention to Vatican archivist and historian Dr. Johan Ickx, author of The Pope’s Cabinet: Pius XII’s Secret War for Saving Jews. It failed, however, to explain that Ickx also once believed that the Vatican concentrated on baptized Jews—until he studied the new archives. “When I read all these documents, I discovered a regular structure that worked in secret and that gave aid to Jews in many ways, through secret as well as official channels,” Ickx has explained. This structure that he calls “the bureau” was active at the local, national, and global levels. Local bishops were involved, as were nuncios in Nazi-occupied countries who tried to postpone deportations of Jews, hide them, or procure visas so they could escape. “They were all active, doing what they could to smuggle people out of dangerous countries to safer ones, and to save as many Jews as possible from the Nazis’ grasp.” As Ickx further explained, “This office for the Jews was unique—no other government offered practical help of this kind. Many of the bishops and nuncios who worked on it were honored as ‘Righteous Among the Nations,’ as helpers of the Jews in the Holocaust, although none of them acted independently, but always on orders from the highest authority—from Pius XII.”

The meeting in Rome was held at a time selected to commemorate the 80th anniversary of the October 16, 1943, roundup of Roman Jews by the Nazis. David Kertzer and others have argued that the pontiff did little to help the Jews who were seized that day; more than 1,000 of them were deported and lost their lives. But as historian Michael Hesemann and Professor Matteo Luigi Napolitano of the University of Molise in Italy have documented, Pope Pius XII helped bring such raids to an end. The primary sources and testimonies on this point provide overwhelming proof of Pius XII’s interventions. He used his Secretary of State, Cardinal Maglione, his nephew Carlo Pacelli, Austrian bishop Alois Hudal, and others to save numerous lives. Pius also managed to distribute 550 posters declaring houses to be “property of the Holy See” and forbidding German soldiers and SS men from entering them.

It was through these actions, which came directly from Pius XII, that the convents and monasteries became safe houses for Jewish refugees. Then, on October 25, 1943, Pius XII published in the Vatican newspaper, L’Osservatore Romano, an urgent appeal to grant protection to all persecuted persons, “regardless of race or religion”—an unmistakable reference to Jews.

Professor Napolitano emphasized that Pius XII was far from silent during the wartime era, beginning his pontificate with the widely acclaimed encyclical Summi Pontificatus—a searing indictment of racism and totalitarianism. Unfortunately, the WSJ piece neglected even to mention Professor Napolitano’s address or his scholarship.

One of the most sensational findings presented in Rome was the discovery of “Birolo’s List”—4,400 names of people who were hidden in 182 Roman monasteries during the German occupation. At least 3,200 people on the list have been identified as Jewish. Gozzolini Birolo, a Jesuit priest, prepared this list at the request of Father Robert Leiber, a close advisor to Pope Pius XII. The list shows what Pius’s defenders have always maintained: that after the Jewish roundup, Pius ordered convents and monasteries to shelter and care for Jews, permitting more than 80 percent of Rome’s Jewish population to survive the German occupation.

Father Roberto Regoli of the Pontifical Gregorian University was portrayed in the WSJ article as a papal critic, but that is far from true. Regoli emphasized Pius XII’s close relations with FDR and the Allies and the pontiff’s active involvement in efforts to overthrow Hitler. In a separate interview, Regoli spoke of a previously unknown Vatican document from early 1939 entitled “Measures Adopted by the Holy See in Favor of the Jews,” outlined just days before Pius XII was elected pope. From then on, Pius XII led the Vatican’s humanitarian efforts on behalf of the endangered and persecuted. “In the new Vatican documentation,” Regoli said, “a worldwide network of support for Jews is discernible.”

While misrepresenting Regoli, the WSJ accepted speaker Giovanni Coco’s dubious claims against Pius XII. Coco pointed to a letter dated December 14, 1942, from a German Jesuit to Father Leiber, informing the Vatican about “SS-furnaces” that were killing up to 6,000 Jews and Poles each day in German-occupied Poland. According to Coco, this showed that the pope was “the head of state best informed about the Holocaust.” The evidence shows no such thing.

This December 14th letter was dated four days after Raczyński’s Note, an official diplomatic memorandum from the government of Poland. The Note was sent to the foreign ministers of all the Allies, informing them about the unfolding genocide at the hands of Germans and calling for help. A December 17th Allied joint statement reflected this plea to the whole world. And the British military intercepted even earlier reports that detailed the early stages of the Holocaust.

Moreover, on Christmas Eve, less than two weeks after the date on the letter (we don’t know when or even whether he actually received it), Pius issued his own 1942 Christmas address, in which he spoke of “hundreds of thousands who, without any fault on their part, sometimes only because of their nationality or race, have been consigned to death or gradual extinction.” The New York Times editorialized, “This Christmas more than ever he is a lonely voice crying out of the silence of a continent.”

The evidence shows the pope was neither silent nor indecisive about the Holocaust. Pius XII was a philo-Semite, not an anti-Semite. To the extent Pius XII measured his words and actions carefully during World War II, he was keenly aware of Nazi retaliation for any “subversive” activities. To this end, Pius XII followed the counsel of the anti-Nazi German Resistance and the Polish bishops. The latter received outspoken anti-Nazi pastoral letters from Pius XII and were most grateful, but chose not to publicize them, lest they “furnish a pretext for further persecution,” as one bishop explained. Even the author of the December 14th letter urged the Holy See not to make public what it revealed, lest his life and the lives of the others be jeopardized.

Those who write in this arena should understand that sinners can rise above their limitations and faults during times of crisis and even turn away from their sins.

Perhaps the most egregious error in the WSJ article relates to Monsignor Angelo Dell’Acqua, a Vatican official who, as a young wartime aide, held some anti-Jewish beliefs. Though it’s not mentioned in the article, in 1943, he complained that Vatican officials were too concerned with saving Jews at the cost of other matters. The WSJ piece claims that Monsignor Dell’Acqua unduly influenced Pius XII.

Despite his prejudices, Dell’Acqua intervened for many Jews during the war. In fact, he eventually broke free from his regressive attitudes and came to see the Jewish–Catholic relationship with new eyes. Two famously philo-Semitic popes, St. John XXIII and St. Paul VI, recognized this, as did the Jewish community, which published favorable articles on Dell’Acqua’s fight against prejudice after the war. Dr. Ickx ends his book discussing “Pope Paul VI’s historic visit to the Holy Land in 1964, during which the Vatican delegation, including Monsignor Dell’Acqua, who stood at the Pope’s side, lit six candles in memory of the six million Jews killed by the Nazis.”

Those who write in this arena should understand that sinners can rise above their limitations and faults during times of crisis and even turn away from their sins. Father Hubert Wolf explained: “In the Curia, too, there were people well-disposed toward the Jews, as well as some who were anti-Semitic. But they all had in mind the Church’s mission and duty to help people in need as quickly and as comprehensively as possible—regardless of their nationality or ethnicity. This basic approach of Christian charity can be clearly recognized.”

Such charity resounds in the words and deeds of Pope Pius XII, before, during, and after the war—even if some reporters and writers cannot acknowledge it.

Public domain image from Wikimedia Commons.