In June 1943, at the height of World War II, Pope Pius XII promulgated the encyclical Mystici corporis Christi, a profound theological reflection on the Church as the “mystical body of Christ.” The pope intended in part to correct some theological errors concerning the Church. Yet he also held before his eyes the sociopolitical devastation of Europe and of the world, and this, too, informed his reflection on the corpus mysticum at that moment. The pope laments “the vanity and emptiness of earthly things … when Kingdoms and States are crumbling.” He begs his audience to “turn their gaze to the Church” and “contemplate her divinely-given unity—by which all men of every race are united to Christ in the bond of brotherhood.”

How might contemplation of the mystical body of Christ—an eminently Eucharistic mode of conceiving the community of the faithful—inform our thinking about politics? In Mystici corporis Christi, Pius XII offers political lessons in two ways. He chastens ordinary political bodies by underscoring what they are not, and he holds out a positive vision of the Church as the only efficacious vehicle of authentic peace and unity in the world.

The teaching of Mystici corporis is worth our attention, because it straddles premodern and modern understandings of the Church in the world. On one hand, Pius XII treats the visible Church as a structured juridical institution with due authority over its members. On the other hand, he departs from earlier defenders of the corpus mysticum by silently prescinding from explicit claims about the Church’s political power, and he anticipates Dignitatis humanae by condemning physical coercion of religious practice. In short, Pius XII shows us that a premodern ecclesiology need not issue in premodern ecclesial politics. Instead, he stresses the Church’s role in transforming political society from within.

In Mystici corporis Christi, Pius XII offers political lessons in two ways. He chastens ordinary political bodies by underscoring what they are not, and he holds out a positive vision of the Church as the only efficacious vehicle of authentic peace and unity in the world.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.Distortions of the Corpus Mysticum

Pius XII’s achievement is best understood against historical shifts in the meaning of the term “mystical body.” As theologian Henri de Lubac explained, the early Church fathers emphasized the oneness of Christ’s body, stressing the mysterious unity of 1) the historical Christ, 2) the sacramental veil under which his sacrifice is re-presented on the altar, and 3) the ecclesial communion effected by participation in the Eucharist. Corpus mysticum originated as a descriptor for the second of these three dimensions of the one body of Christ. “Mystical” alluded to the mystery of the Eucharist, or the hidden power by which the sign produced what it signified: the Eucharist gave life to the Church. Eucharist and Church were inseparable realities.

Yet de Lubac shows that by the twelfth century, the term “mystical body” had shifted from the Eucharist to the Church. In reaction to some overly spiritualizing trends, scholars began stressing the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, describing it as Christ’s “natural body,” “true body,” or simply “corpus Christi”—the body of Christ. Contrasted with this fleshy reality was Christ’s “mystical” presence in the Church. The resulting transfer of corpus mysticum to the Church culminated in the 1302 promulgation of the bull Unam Sanctam by Pope Boniface VIII, who declared that the Church represents “one sole mystical body whose Head is Christ.” Boniface VIII holds that the pope, Christ’s representative on earth, is the sole head of the visible Church, in possession of both spiritual and temporal swords, and is therefore empowered to subordinate earthly rulers to himself.

Political reactions against the pope were strong. As the Church modeled itself on an imperial polity, so did political rulers seek to sanctify and exalt their own power by borrowing practices, symbols, and terminology from the Church. Ernst Kantorowicz explains that this borrowing gradually caused the “mystical body” language to migrate from sacred to secular. Once the term corpus mysticum became linked to the political dimension of the institutional Church, it was easily transferred to other human societies and eventually became interchangeable with concepts like the “body politic.” De Lubac reports that by the nineteenth century, the bishops at Vatican I were generally astonished and perplexed by the description of the Church as “mystical body of Christ.”

In this way, the idea of the “mystical body” underwent a gradual process of distortion, to the point that it played into the hands of emergent modern nation-states that grasped for the claims of divine right. Extending de Lubac’s arguments, political theorist Sheldon Wolin argued that the transfer of mystical bonds of unity from Church to modern state led to a new form of politics that became increasingly nationalistic and quasi-religious. In the twentieth century, this trend culminated in the totalitarian ideologies of National Socialism and Communism. The political error Pius XII corrects in Mystici corporis is precisely this conflation of sacred and profane societies: he wants to reclaim the meaning of “mystical body” for the Church and distinguish it from ordinary political societies, thereby rejecting all political idolatry.

Once the term corpus mysticum became linked to the political dimension of the institutional Church, it was easily transferred to other human societies and eventually became interchangeable with concepts like the “body politic.”

Demystifying the Political

In the encyclical, Pius XII works through the expression “mystical body of Christ” systematically, explaining how each term applies to the Church: how is the Church a body? Why the body of Christ? Why a mystical body? Like a body, the Church is an “unbroken unity” that is “definite and perceptible to the senses.” It has a well-structured “multiplicity of members” that serve various functions like bodily organs, all interdependent and oriented to the flourishing of the whole. As a body requires food and water, so Christ gave the Church the sacraments—especially the Sacrament of the Eucharist—to nourish and sustain it. Working through Scripture, the pope portrays Christ as the “Founder, the Head, the Support, and the Savior” of his ecclesial body.

The encyclical’s political significance lies primarily in its treatment of the corpus mysticum. Pius XII defines a “mystical body” by way of contrast with two other kinds of bodies. A “natural body” is a single organism in which the parts are totally subsumed in the whole and cannot subsist apart from it, as my kidney cannot subsist apart from the rest of me. Meanwhile, a “moral body” is an ordered social group whose members retain their own individuality; they are united not physically but by “the common end, and the common cooperation of all under the authority of society for the attainment of that end.” An authentic community, a moral body is united by its members’ shared pursuit of a common good. Pius XII also highlights the juridical bonds of a moral body: external rules, practices, and structures of authority that help direct members to their end.

The Church on earth is a moral body united for a “supremely exalted” end: the increase and sanctification of her members for God’s glory. Juridical elements that “externally manifest” this unity include shared participation in the liturgy, public profession of the same faith, and obedience to the same Church laws and ecclesial hierarchy. Yet as a “mystical body,” the Church is further united by a mysterious principle that exceeds its juridical bonds. That principle is the Holy Spirit, which fills the whole Church and infuses into its members the theological virtues that bind them to Christ and in Christ to each other with bonds of love “vastly superior” to that of any natural or moral body. As a result, Pius XII writes that the mystical body of Christ is “far superior to all other human societies; it surpasses them as grace surpasses nature, as things immortal are above all those that perish.”

By distinguishing “moral body” from “mystical body,” Pius XII corrects problematic conflations of the two. He undoes the confusing, overly-politicized misapplications of the “mystical body” that de Lubac lamented, without compromising the juridical character of the Church. In locating the birth of the Church in the outpouring of blood and water from Christ’s pierced side, he maintains the dynamic oneness of the historical, sacramental, and ecclesial forms of the body of Christ. The unity of the Church is generated by the redemptive oblation of Christ, which is continually re-presented in the Eucharistic sacrifice.

The encyclical addresses the political situation of the 1940s through a via negativa: by clarifying what the mystical body of Christ is, Pius XII underscores what ordinary political communities are not. He strips the mystical from merely human societies, and he emphasizes the inferiority of political bonds and political authority compared with the bonds and authority of the Church. He implicitly affirms the central message of the 1937 encyclical Mit Brennender Sorge (“With Burning Anxiety”) that he helped draft for his predecessor Pope Pius XI, which denounces political idolatry and the religious impulses behind totalitarian regimes. In short, Pius XII’s retrieval of the corpus mysticum from the secular underscores the theological error of totalitarianism.

An authentic community, a moral body is united by its members’ shared pursuit of a common good. Pius XII also highlights the juridical bonds of a moral body: external rules, practices, and structures of authority that help direct members to their end.

The Church in the Modern World

The via negativa, however, tells only half the story. The political community is not mystical, but the Church remains a juridical body with a sociopolitical role. Yet in contrast to earlier defenders of the Church as the mystical body of Christ, Pius XII does not claim coercive political power for the Church; rather, his encyclical models a more spiritual, sacramental mode of ecclesiastical engagement with the modern world, and so helps pave the way for Vatican II.

Two key sources for Pius XII’s reflection on the Church are Pope Boniface VIII and St. Robert Bellarmine. Both identify the “mystical body of Christ” with the Church of Rome, headed by the Roman Pontiff as the earthly Vicar of Christ. Both defend the supremacy of the Church over political societies and champion the Church’s power to intervene coercively in political affairs. Boniface VIII’s Unam Sanctam directly subordinates political authorities to the Church, while Bellarmine champions a more limited, “indirect” power of Church authorities to intervene coercively when politics bears on spiritual matters.

Pius XII follows his predecessors in upholding the unity of the visible and invisible Church, the primacy and universal jurisdiction of the pope, and the superiority of mystical over political bodies. Mystici corporis is rife with echoes of Bellarmine, in particular. However, the pope remains totally silent on the question of the Church’s power to intervene coercively in political affairs. His most explicit comment on politics consists in an exhortation that Church leaders offer “earnest supplications” for political rulers, that they might rule with wisdom and “assist the Church by their protecting power.” Needless to say, prayer for the protection of the Church is a far cry from direct intervention in politics.

Silence does not entail repudiation; Pius XII’s private views on the scope of the Church’s temporal power are unknown, as he left no personal notebooks behind. Nevertheless, at a minimum, the public silence of Mystici corporis acknowledges the impracticality of more directly political models of ecclesiastical jurisdiction. Pius XII recognizes that the new, increasingly secular politics of the modern world calls for the Church to concentrate on its spiritual role in transforming hearts and minds, renewing political society from within rather than by means of external imposition. As he put it in the first encyclical of his pontificate, Summi Pontificatus: “Safety does not come to peoples from external means, from the sword which can impose conditions of peace but does not create peace. Forces that are to renew the face of the earth should proceed from within, from the spirit.”

Pius XII recognizes that the new, increasingly secular politics of the modern world calls for the Church to concentrate on its spiritual role in transforming hearts and minds, renewing political society from within rather than by means of external imposition.

Pius XII suggests that spiritual and temporal planes intersect in the common yearning for peace, which is the key to his positive political teaching in Mystici corporis Christi. The pope agrees with St. Thomas Aquinas, who argues that while justice can “remove obstacles to peace,” only the supernatural bonds of charity can truly effect peace. Authentic peace begins with a person’s internal ordering toward God, which then flows outward into a love of neighbor that extends universally. Consequently, although political societies might aim for lasting temporal peace as their end, they cannot bring it about by political means alone. For Pius XII, the state badly needs the Church, but his teaching leaves space for greater institutional separation between the two than traditional medieval or Tridentine ecclesiology allowed.

Mystici corporis hints at this separation when Pius XII condemns physical coercion of religious practice, maintaining that “straying sheep” must enter the Church “of their own free will; for no one believes unless he wills to believe.” The claim is unremarkable as applied to the unbaptized, but in context, the pope also includes among the “straying sheep” “those who, on account of regrettable schism, are separated from Us.” The category embraces both schismatic Catholics and members of other Christian denominations, making no distinction between unbaptized and baptized. The encyclical thus anticipates Dignitatis humanae and combines what Thomas Pink calls a “jurisdiction-centered” model of religious authority with a “person-centered” model of religious liberty: Pius XII affirms the Church’s authority over the baptized but rejects certain coercive means of promoting the faith.

In this way, Pius XII serves as a transitional figure between Vatican I and Vatican II. Some scholars characterize him as traditional and even anti-modern, especially given his staunch defense of the Leonine neo-scholastic tradition. Yet in Mystici corporis Christi, his embrace of religious liberty and emphasis on the contributions of laypeople to the corpus mysticum anticipates Vatican II, which grants to the laity a special role in leavening the secular sphere with the truth of the Gospel. Moreover, the pope paves the way for Vatican II by implying that the best thing the Church can do for the world is to be the Church—to live out the sacramental mission of Christ’s mystical body ever more faithfully.

Underscoring this final point, Pius XII turns to pastoral considerations near the end of his encyclical: he exhorts the faithful to participate in daily Mass, frequent confession, personal prayer, mortification, and works of mercy. He begs them to offer up their suffering for the redemption of the world. These practices are not minor, weak, or irrelevant responses to a world crisis; on the contrary, the pope believes they are powerfully efficacious and necessary, strengthening the bonds uniting the mystical body of Christ and sowing the seeds of peace. His counsel is spiritual in nature, but sociopolitical in its effects.

Emphasizing the unity of all humanity, Pius XII suggests that just as the grace of Christ’s redemptive sacrifice rent the temple veil “violently from top to bottom,” only grace can break down the partitions dividing humankind in the war-torn world of the 1940s—and in our own.

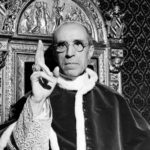

The featured image is in the public domain courtesy of pexels.com.