The Harvard law professor Cass Sunstein is a prolific author with very wide-ranging interests. He has written (and in some cases co-authored) books on behavioral economics; on lies, rumors, and conspiracy theories; on republican theory and political conflict; on feminism; on free speech and dissent; on animal rights; even on Star Wars—and I’m leaving some out. In many of the fields in which Sunstein has written, I would hardly be qualified to judge his work. (Aren’t the Ewoks just really small Wookiees?) But his latest effort, How to Interpret the Constitution, is one that I can confidently say is very disappointing. This brief book has three primary characteristics: assertion, excessive repetition, and fallacious logic.

Sunstein’s argument is structured as follows. The Constitution does not itself tell us anything about how it is to be interpreted. Therefore, each of us—but judges especially, given their interpretive authority—must choose a “theory” of interpretation. The guiding principle of that choice is to seek what “would make the American constitutional order better rather than worse.” This choosing, Sunstein maintains, grows out of a process of reasoning known as “reflective equilibrium,” a threadbare idea advanced by John Rawls a half century ago, which Sunstein insists several times is “the only game in town.” This in turn means that we check our tentative constitutional principles against their practical results—the latter being “fixed points” to which we are morally attached—and adjust our theory to our practice until it reliably yields a pattern of outcomes we can endorse (though not perhaps a result we will applaud in every single case).

When all is said and done, Sunstein settles on a “moral reading” of the Constitution, patterned largely after the project of the late Ronald Dworkin, in preference to any form of originalism, “traditionalism,” or (though he seems to forget it almost as soon as he sketches it) the “democracy-reinforcing” theory of John Hart Ely. The decisive reason for a “moral reading,” which molds the Constitution’s few alleged “majestic generalities” (freedom of speech, due process, equal protection of the laws) to suit our own preferences is that they are, well, our own preferences. That is to say, our “fixed points.”

Sunstein’s argument is structured as follows. The Constitution does not itself tell us anything about how it is to be interpreted. Therefore, each of us—but judges especially, given their interpretive authority—must choose a “theory” of interpretation. The guiding principle of that choice is to seek what “would make the American constitutional order better rather than worse.”

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.Sunstein generously allows that one could choose any coherent “theory of interpretation” of the Constitution. But a great proportion of the book is devoted to analysis and critique of originalism, which Sunstein rightly recognizes is now the dominant approach on the contemporary Supreme Court. It is not really coherent, in his view. But why? Because, he asserts, it fails to achieve “reflective equilibrium” with his “fixed points.” That is to say, with his moral preferences, broadly considered.

Some readers will wonder why Sunstein claims to have a “theory” of interpreting the Constitution. Others will wonder what it means, in his view, to “interpret” a text. Sunstein insists that appropriate anchors in preferred results are “not, or not simply, fixed points about morality and justice. They have to be fixed points about constitutional law”—and then he immediately proceeds to enumerate preferred results of his “interpretation” of the Constitution. Which is to say, he is not interpreting the Constitution at all. He is working backward from outcomes, arriving at premises that will produce his conclusions, and calling that “interpretation.”

I lost track of the number of times Sunstein tells us that a theory of constitutional interpretation that permits the federal government or the states to discriminate among persons on the basis of race or sex, narrows the boundaries of the freedom of speech set in just the last sixty years, or reverses precedents on same-sex marriage or a right to contraception, is for such reasons alone a failed theory. This is an astonishing inversion of legal reasoning.

There are, of course, prominent jurists and constitutional scholars who plausibly claim, for instance, that on originalist grounds we may conclude that racial discrimination by state governments is forbidden. Sunstein knows this perfectly well. But suppose they are wrong, as Sunstein repeatedly insinuates they are (without any showing of evidence). And suppose we grant that he is right about the other results he is sure originalism will not provide. It is the rankest ignoratio elenchi—the strutting forth of an irrelevance rather than a refutation—to say, as he does, that “it follows that originalism is wrong.” Nothing follows from our disliking a conclusion if we have done nothing to refute the evidence and the premises that led to that conclusion. Unfortunately, nothing is just what Sunstein provides.

In a similar vein, Sunstein repeatedly asserts that “there is nothing that interpretation just is.” I happen to think that statement plainly wrong on its face, and in another place might feel obliged to explain why that is so. But this is a review of what Sunstein has to say on the subject, and not once in this book does he give the reader a reason to believe he is right about that. He supplies various accounts of motivations for rejecting the view that interpretation “just is” something, that something being an effort to give an informed account of the fixed meaning of a text. But motivations for rejecting an argument, it should go without saying, are not reasons.

Perhaps Sunstein has spent so much time on the terrain of the behavioral sciences, where various impulses and motives for action commonly stand in for reasons, that he cannot find his way back to the law or to textual interpretation, where only reasons minted in the coin of rational argument have any purchasing power. But that is speculation. What is not speculation is that in the 165 pages of this book, there is not one logically valid argument for rejecting originalism and adopting Sunstein’s “moral reading” of the Constitution. There is simply a string of begged questions.

Such a substantial proportion of this book is devoted to textualism, originalism, and traditionalism that it is hard to escape the sense that Sunstein protests too much by repeatedly claiming that his moral-philosophizing “reflective equilibrium” is “the only game in town.” And in truth, he leaves his own preferred approach woefully underdeveloped.

But perhaps the imbalance is not surprising. When one looks at the work of the Supreme Court and the federal circuit courts of appeals, or at the most influential work being produced by legal scholars today, it appears that originalism and its close cousins, textualism and traditionalism, are truly the only game in town. Originalism itself is not one thing but several, with rival schools of thought about just how one may best arrive at the sound reading of the Constitution’s fixed meaning. Sunstein supplies something of a tour of these approaches, and even in his own critical account of them the reader can discern that they all have the virtue of being principled in insisting on premises first, conclusions after. It is a fair question for any originalist argument whether its advocate has tinkered with his premises or evidence in order to arrive at his desired conclusion. But at least originalists, as a class, observe the formalities of valid argument. This cannot be said for Sunstein.

I noted at the outset that Sunstein’s oft-repeated thesis is this: “Any theory [of constitutional interpretation] must be defended on the ground that it will make our constitutional order better rather than worse.” This statement itself he never defends; it is for Sunstein simply an axiom. And it is clear that by “better” he does not mean that the constitutional order becomes more perspicuous, or truer to its meaning or to the purposes of those who bequeathed it to us. He means more just in its broad substantive results.

It is a fair question for any originalist argument whether its advocate has tinkered with his premises or evidence in order to arrive at his desired conclusion. But at least originalists, as a class, observe the formalities of valid argument. This cannot be said for Sunstein.

But pursuing substantive justice, measured by “fixed points” standing apart from the Constitution (as Sunstein’s are), is precisely what interpreters of the Constitution must not do. At least we may say that it is not the job of interpretation as such. Once having interpreted the Constitution and laws, the work of lawmaking and administration has only begun, while the work of adjudication is essentially finished. Legislators and executives, in carrying out their proper functions, are free to pursue—and should pursue—those just aims in law and policy that will “make our constitutional order better rather than worse.” That is because legislators and executives are enjoined to do whatever the Constitution permits in their pursuit of the common good and are otherwise free to cling to their own “fixed points.” Judges, on the other hand, are not free to pursue justice as such, because they are enjoined to do only whatever the Constitution requires in the pursuit of justice—understood as norms of justice internal to the Constitution, not external to it.

The legislator or executive appropriately asks, “what can I do in pursuing justice, consistent with the Constitution and any other laws that bind my actions?” But the judge appropriately asks, “what must I do in pursuing justice, consistent with the Constitution and any other laws that bind my actions?” This difference is vital to the separation of powers, and no scintilla of its recognition appears in this book. To make the work of interpretation identical to the job of “making things better” is a category error. Unfortunately, that error is the foundation of Sunstein’s How to Interpret the Constitution.

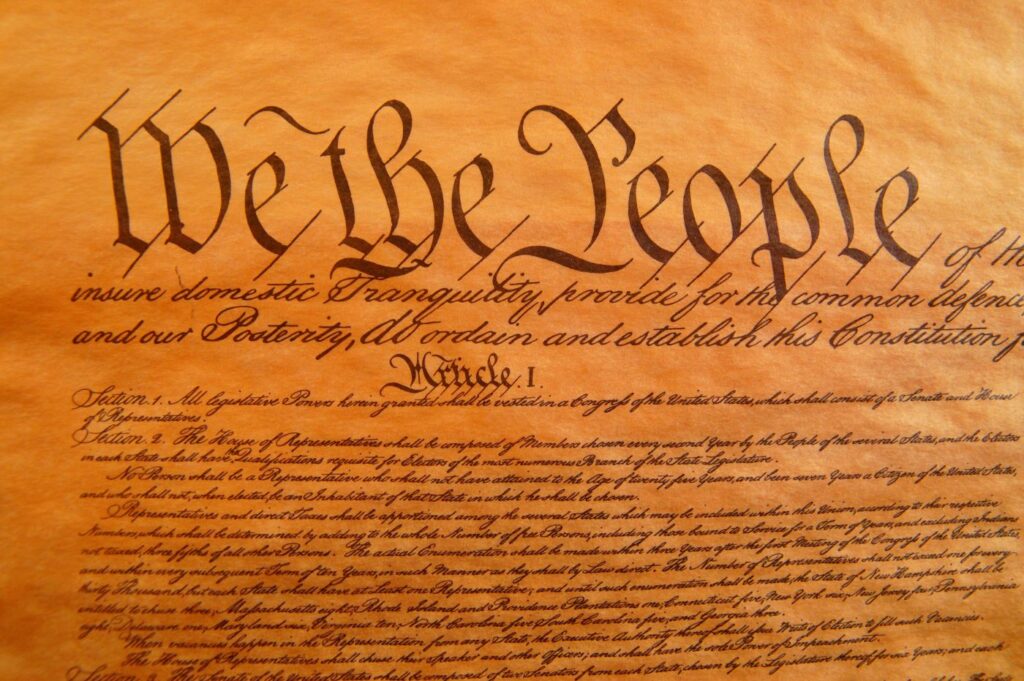

The featured image is courtesy of Adobe Stock and is in the public domain.