In last month’s holiday book recommendations here at Public Discourse, readers were treated to a little tiff between Editor-in-Chief R. J. Snell and Managing Editor Elayne Allen. Editor Snell suggested that readers of Jane Austen ought to like Anthony Trollope even more, because the latter offers “more interesting characters and writing that is funny.” Editor Allen retorted that this opinion was “misguided” and averred that “Persuasion is of course hilarious.”

Well. I’m something of a third-degree Janeite, and I agree that editor Snell was wrong to insinuate that Austen is unfunny. I’ve begun myself to read Trollope’s Can You Forgive Her? and so far can give the author high marks for a dry wit, but if you’re not picking up the humor in Austen’s novels, you’re missing something. Yet neither of them merits the encomium “hilarious.” On a laugh meter, I’d put both Austen and Trollope about equal, say a 3.5 out of 10.

This small contretemps got me thinking that funny is a good way to start the year, but also about what makes for successfully humorous writing. Lately I’ve been reading a great deal of P. G. Wodehouse—a solid 10 on the laugh meter, in my view—and he gives a master class on writing funny. As I said in a column devoted to Wodehouse in 2020, he displayed a “perfect mastery of English prose.” Wodehouse’s sentences are grand formal utterances, so correctly outfitted in evening dress that they would be condemned as pompous, were it not for his adroitness in equipping them also with clown shoes, spinning bow ties, and tearaway trousers.

At the risk of killing a joke by analysis, consider this celebrated sentence from a story in Mr. Mulliner Speaking, coming in the midst of a man’s effort to escape a room by stealth: “At this moment, however, the drowsy stillness of the summer afternoon was shattered by what sounded to his strained senses like G. K. Chesterton falling on a sheet of tin.” When I posted this quotation on Twitter recently, someone agreed it was funny but asked me “why G. K. Chesterton?” I pointed out how much less funny it would be to have written “a fat man falling on a sheet of tin.” Wodehouse makes the reader think of a particular fat man—a famously stout man, one who was quite capable of laughing at himself, but whom we do not ordinarily picture in our mind’s eye falling on sheets of tin. And why should something sound like Chesterton taking such a fall? Don’t all large human bodies falling on sheets of tin sound alike? The absurd specificity makes for another laugh. Page after page, Wodehouse springs such surprises on our imagination.

Start your day with Public Discourse

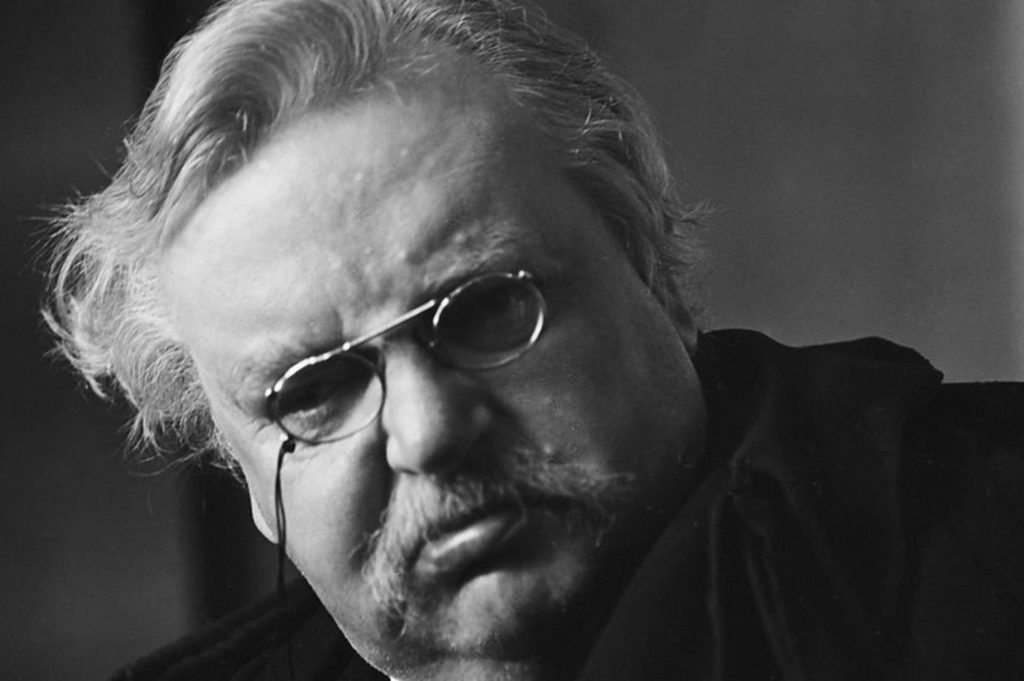

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.Mel Brooks, in his recent memoir All About Me! My Remarkable Life in Show Business, occasionally pauses to reflect on how comedy works. It is a “juxtaposition of textures,” he says. (Just so—Wodehouse has that down pat.) “Inept idiots will always be fun,” Brooks also says, recalling his writing the Get Smart TV series in the 1960s. (Think of Bertie Wooster, the epitome of ineptitude.) And Brooks shows as well as tells how to be funny. When he accepted the Oscar in 1969 for writing The Producers, he said from the stage: “Well, I’ll just say what’s in my heart. Ba-bump! Ba-bump! Ba-bump! Ba-bump!”

Brooks ends his chapters on the banner year in which he wrote, produced, and directed Blazing Saddles and Young Frankenstein, both huge hits, this way: “And I can also honestly say that 1974 was a much better year for Mel Brooks than it was for Richard Nixon.” Okay, joke-killing time again. Why is that so funny? Rewrite it and see. Suppose Brooks had written: “And I can also honestly say that Richard Nixon did not have a good year compared to me.” It falls flat. “Richard Nixon” is the punch, or what Mark Twain called the “snap.” It has to come at the end, and catch the reader or listener unawares. This is the only time Richard Nixon is ever mentioned in All About Me, and Brooks is counting on your knowing what happened to him in 1974. The name is the surprise sting in the tail of the last sentence in the chapter, and it’s laugh-out-loud perfect.

Funny matter without artful telling fails to win home, and a story with nothing intrinsically funny won’t get laughs no matter how it’s told.

Twain, in “How to Tell a Story,” wrote: “The humorous story is American, the comic story is English, the witty story is French. The humorous story depends for its effect on the manner of the telling, the comic story and the witty story upon the matter.” I don’t know that I quite see the national differences Twain sees. Still, there is something to the manner vs. matter distinction he draws. Yet the difference may be one of emphasis. Funny matter without artful telling fails to win home, and a story with nothing intrinsically funny won’t get laughs no matter how it’s told.

Twain himself was famously funny in the manner of his storytelling. I’ll refer again as I did in November to his outrage (real or feigned) at having his precious “Jumping Frog” story ill-translated into French. All the matter was there in the translation; what was gone, and even more so in his hilarious “clawing back” of the story into English, was the inimitable Twain manner of telling the tale. Even when he was in deadly earnest—and sometimes he was deadly indeed—Twain’s tone was always wry, his voice a mocking rebuke to folly.

There is a lot of mileage to be gained out of mockery, and nowhere more than in satire and parody—think of the success these days of the Babylon Bee. But successful parody depends on close study, intimate familiarity with the target, and that can often produce a certain gentleness and sympathy in the result. (Brooks tells us that the success of his films depended on his authentic love for Broadway, westerns, horror films, Hitchcock, etc.) The English writer Max Beerbohm once published a volume titled A Christmas Garland, in which all the pieces were Christmas-themed parodies written in the voices of “H*nry J*ame*s,” “R*d**rd K*pl*ng,” and so forth. Here was Beerbohm’s “G. K. Ch*st*rt*n” (sure, why not GKC again—he was a good sport), in an essay titled “Some Damnable Errors About Christmas”:

We do not say of Love that he is short-sighted. We do not say of Love that he is myopic. We do not say of Love that he is astigmatic. We say quite simply, Love is blind. We might go further and say, Love is deaf. That would be a profound and obvious truth. We might go further and say, Love is dumb. But that would be a profound and obvious lie. For love is always an extraordinarily fluent talker. Love is a wind-bag, filled with a gusty wind from Heaven.

If Beerbohm hasn’t got Chesterton’s voice, may I gain a hundred pounds and fall on a sheet of tin to the amusement of my friends. Only a sneaking fondness for Chesterton’s orotund style—or at least respect enough for it to master the disguise—could account for such spot-on mimicry. And once again, the “snap” comes smartly at the end.

There is a lot of mileage to be gained out of mockery, and nowhere more than in satire and parody—think of the success these days of the Babylon Bee.

Some of the best funny writing does have a kind of gentle sympathy for the targets it skewers. The British short story author “Saki” (H. H. Munro), describing a character “widely credited with a rather unpleasant wit,” continues in his own much more pleasant way: “The censorious said she slept in a hammock and understood Yeats’s poems, but her family denied both stories.” Suddenly we cannot quite dislike such a woman.

James Thurber was a master of this sort of thing. His talent ranged from mildly droll social commentary to sharp squinting at the absurdities of the human condition, but there didn’t seem to be a mean bone in his body. Even his send-up of the “life of the party” type in “The Funniest Man You Ever Saw” was done at arm’s length, so that we see the hapless boob only in the third-person descriptions of the people who actually think he’s a hoot.

As Thurber surely knew, it’s difficult to be consistently funny. The deathbed adage attributed to various actors (it appears to have been Edmund Gwenn, best-known for Miracle on 34th Street) is, “Dying is easy. Comedy is hard.” If truth be told, even some of Shakespeare’s jokes don’t travel any more. (The Merry Wives of Windsor has some awful stuff in it, but then it was written on demand for Queen Elizabeth.) And O. Henry had it right, surely, when he wrote in “Confessions of a Humorist” in the voice of a man who, having made a modest success at writing funny stories, has to keep at it day in and day out. Desperate for fresh material, he becomes “a harpy, a Moloch, a Jonah, a vampire” to everyone he knows. Friends, acquaintances, his own wife and children—he exploits them all, like a starving man diving in a dumpster, ravening for the merest scraps of wit, malapropism, or humorous situation. Finally he has to throw it over and enter into business with an undertaker, for his peace of mind.

So turn to our friends the humorists, dear readers, with gratitude for anyone who can make us laugh with such seeming ease as these writers. Hilarity is hard work. Just ask Jane Austen.