To discover more excellent reads and cinema selections, don’t miss our Isolation Bookshelf collection.

It must have been in the early 1980s, on a visit to my parents when I was in graduate school, that I chanced across a book with the arrestingly silly title The Brinkmanship of Galahad Threepwood (1964), by some fellow named P.G. Wodehouse. What it was doing in my parents’ house—and now that I think of it, why it was the only Wodehouse book in the house—I don’t recall ever discovering. But the book made me laugh out loud while reading silently to myself, alone in a room, and the list on one of the front endpapers of more than seventy other books by the author was a promise of more laughter to come.

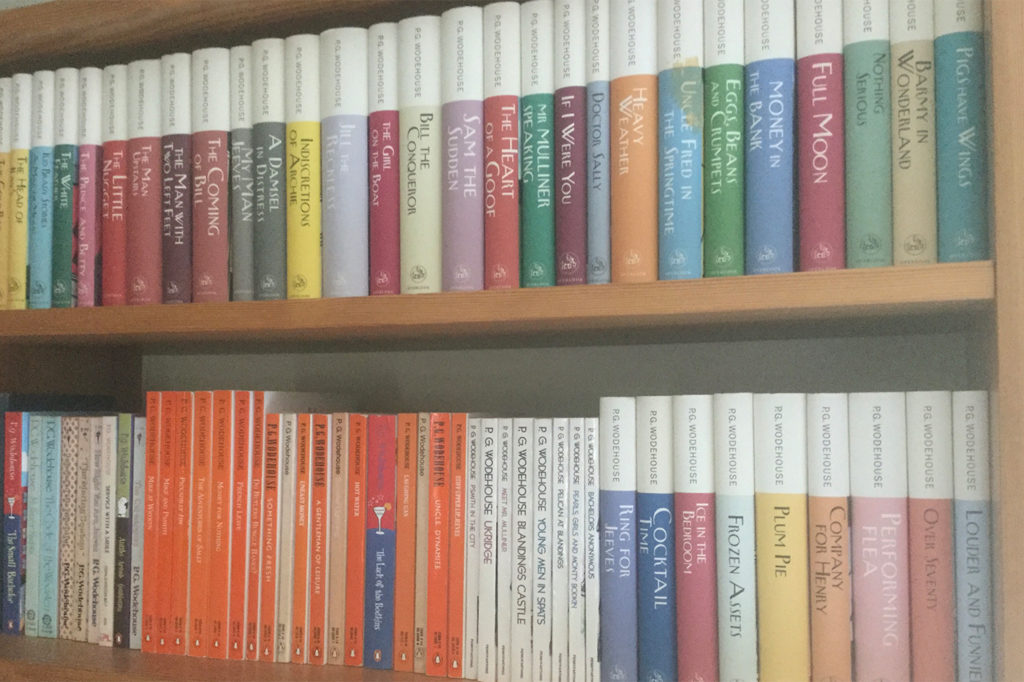

In short, I was hooked. I kept my eyes peeled for books by Pelham Grenville (“Plum”) Wodehouse, new or used, in every bookstore I entered over the years. The age of online book shopping made adding to my collection easier, and when Overlook Press (in conjunction with Everyman’s Library in the UK) began to produce a uniform edition of all of his books, the temptation was irresistible to become a “completist.” In various editions, hardcover and paperback, omnibus and singles, new and used (even a handful of first editions of no great value), I think I now have all of Wodehouse’s books (most of them are pictured above), which were originally published from 1902 (the year he turned 21) to 1975 (the year of his death).

What is it about Wodehouse that makes so many lifelong enthusiasts of his readers? The world described in his novels and stories—at English country houses, in the clubs of London, on New York’s Broadway—seems to come to us from an early 1920s time capsule, even though the majority of his books were written later than that. His tales always bring the reader to a kind of happy ending, and along the way display no malice whatsoever, even for characters who might deserve to be despised (such as the fascist Roderick Spode). There are no murders, no situations truly fraught with tragedy or grave danger.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.Perhaps it is Wodehouse’s attention to meticulous plotting. We know in advance, for instance, that the very appealing young man and woman will be together at the end, but the author can still surprise you with unexpected—and hilarious—situations before we get there. When it comes to his many love stories, Wodehouse is the twentieth century’s Jane Austen—girl meets boy, initial disregard turns to something else, wedding bells are finally heard—but armed with a squirting bouttonière.

Or perhaps it is Wodehouse’s perfect mastery of English prose. None of his sentences ever goes awry, though they can be as long and intricate as those in the epistles of St. Paul. Wodehouse’s English is always formally correct, yet it is sprinkled liberally with slang, odd idiomatic expressions, effortless literary allusions, and sudden punch lines that hit you between the eyes.

And then there are his characters. The inimitable Psmith (“the P is silent”), the roguish Ukridge, the indefatigable storyteller Mr. Mulliner, the puttering old pig farmer the Earl of Emsworth. And of course the perfectly amiable twit Bertie Wooster, his priceless brace of aunts (Dahlia, good, and Agatha, bad, but both formidable), his would-be fiancée, the fearsome Honoria Glossop, and his omniscient gentleman’s gentleman, Jeeves. Most Wodehouse fans find their way in via the first-person tales of Bertie. I recommend The Code of the Woosters (1938), which begins with the best description ever written of the experience of a hangover, or Joy in the Morning (1946), published in the U.S. as Jeeves in the Morning.

The latter book just mentioned was finished by Wodehouse while he was interned by the Germans as an enemy alien during the Second World War. This period in his life was almost the entire undoing of his career as a writer. Wodehouse had lived in northern France for several years when the Germans’ sudden invasion in 1940 landed him in the soup, as he might have said. Separated from his wife Ethel for months, he suffered severe privations, ultimately losing sixty pounds. On his release from an internment camp but still in German custody, he agreed, with amazing naïveté and imprudence, to record several humorous broadcasts from Berlin, ostensibly to reassure his readers in America (which was not yet in the war) that he was all right. Of course the Germans used them as propaganda against the British, and popular sentiment in the UK turned sharply against Wodehouse, who came to regret his idiocy for years to come.

Yet even before the larger British public forgave Wodehouse (he was knighted shortly before his death), the most fairminded of his countrymen judged him justly. George Orwell, in his 1945 essay “In Defence of P.G. Wodehouse,” said that “the events of 1941 do not convict Wodehouse of anything worse than stupidity,” and added that “the idea that in 1941 he consciously aided the Nazi propaganda machine [was] untenable and even ridiculous.”

Just how widely Wodehouse was read in his day can be guessed from this Orwell essay. Orwell’s literary judgment was not altogether kind to Wodehouse, and he remarked (social democrat that he was) that “Wodehouse’s real sin has been to present the English upper classes as much nicer people than they are.” Yet he also tells us that of some fifty-odd books by Wodehouse of which he was aware, he had not read “perhaps a quarter or a third of the total,” having discovered the author when he was eight years old. In other words, the hard-bitten Orwell had read some thirty-five or forty of the books Wodehouse had published by 1945!

Why this should be so can be explained by any true aficionado. Wodehouse’s work, from virtually any period of his long career, is amazingly consistent. One learns after a while that when one begins a Wodehouse story, satisfaction is guaranteed. Like a fresh whisky and soda, his work promises an easing of the tensions of daily life, an invitation to merriment, and a quiet contentment that in the end all will be well.