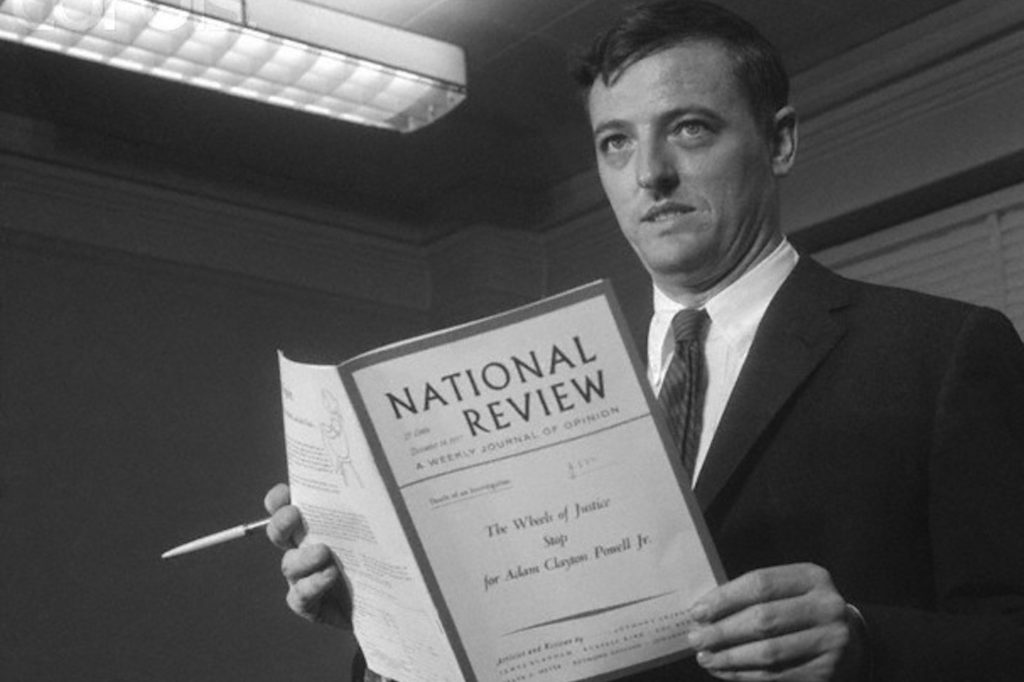

Ramesh Ponnuru has been a writer and editor at National Review for nearly all his career since graduating from Princeton in 1995. In January 2022 he became editor of the magazine, just the fourth in National Review’s history, succeeding William F. Buckley, Jr., John O’Sullivan, and Rich Lowry, who continues with the title editor-in-chief over National Review’s entire operation and its website. Ponnuru is also a nonresident senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and a columnist for Bloomberg Opinion. He and contributing editor Matthew J. Franck spoke in the first week of August.

Matt Franck: I want to begin with some thoughts about the magazine and its place in our politics. You now occupy the seat once held by the legendary Bill Buckley. Matthew Continetti’s history of the last century of American conservatism, The Right, sometimes reads for lengthy passages like a history of National Review, so central has the magazine been to both the intellectual and the political fortunes of the conservative movement. As you reflect on the history of the magazine you now edit—and you’ve been present for more than a third of its history—what stands out for you as National Review’s signal contribution to the American conversation?

Ramesh Ponnuru: I would say that National Review midwifed and nurtured the modern conservative movement into being. Conservatism didn’t have to take the form that it did in the United States after World War Two. It did have some roots; it wasn’t entirely a novelty, and I think Continetti’s book is quite good about that—its beginning the story in the 1920s is helpful in that regard. But we could have had a conservatism that was in some respects more like other countries’ conservatisms and less distinctively American. We could have had one that was more collectivist in nature, for example. And National Review performed both intellectual and eventually political services in bringing that coalition together and expanding it and then steering it toward . . . constructivity, I guess, would be the word.

MF: I don’t want to make this a conversation about Continetti’s book, but we both think highly of it. He could of course have begun the history of American conservatism a century earlier than he did, or a century and a half. I think it was appropriate for him to write a history of modern conservatism that is a century long, rather than just 75 years. The conservatism that characterizes the United States—what you might call the conservatism of classical liberalism—owes much of course to the founding, the revolution, revolutionary principles defended and resuscitated by Abraham Lincoln. And so he could perhaps have written a book that takes us all the way back to the fights between Jefferson and Hamilton, then takes us forward to the Civil War and the stakes in that refounding of the United States. I think that what may be distinctively American about the conservatism espoused by National Review from its beginning has been its sense of this historic legacy, traceable at least to the founding. Do you agree with that?

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.RP: Yeah, that’s right, I have long thought that a good working definition of American conservatism is that it is the enterprise of conserving our political inheritance from the founders—which, as you know, as conservative thinkers (preeminently Burke) have always stressed, is not merely a passive task, but something that requires an enormous amount of labor against the silent artillery of time, among other things. When you were talking about the ways you could tell the story of conservatism’s history, it struck me that it may be that I like Continetti’s choice of the 1920s, in part, simply because it allows him to include Calvin Coolidge’s great Fourth of July speech in which he says, about the Declaration of Independence, “there is a finality that is exceedingly restful”—which is a quote that I think illustrates the point that I just made, which is that the marriage between limited government and a kind of natural law conservatism isn’t something that Buckley just artificially stitched together, but something that in some sense belongs together.

MF: You mentioned Edmund Burke a moment ago, and I noticed in a recent issue of the magazine (August 15) that there’s an interesting short feature article on Edmund Burke making an argument it was very pleasant to see, reminding people that Burke considered himself a liberal as that term is classically understood, though not as it came to be reimagined and redefined in the twentieth century. There’s a certain species of anti-liberal or illiberal conservative today, a species that looks back to Burke as an exemplar of its brand of conservatism, and I think they’re overlooking Burke’s liberalism. He was a defender of the Glorious Revolution of 1688, which installed in his country liberal principles of limited government.

RP: Well, as a Catholic, I have mixed feelings about the Glorious Revolution.

MF: I can well understand that as I’m Catholic, as well, as you know.

RP: I think that illiberal conservatism is in part a salutary reaction against some excesses that are sometimes mistakenly held to be inherent to liberalism. There’s something in the reaction to liberalism that is really deeply encoded into the conservative DNA: a kind of theoretical maximalism. I’m reminded of Richard Weaver’s famous or infamous insistence that modernity took a wrong turn with William of Ockham. So the idea is that every progressive excess that we fight today is in some sense present in embryo in Locke. And I would say that thinking about liberal societies and liberal institutions purely in terms of liberal theorists and liberal theory is a mistake. Those things are important, of course, but there is a process of accumulating knowledge and evolving that is not captured by the theorists and their theories, and so I think you can have a mature appreciation of free government and free markets without idolizing either of those things and without adopting some kind of social contract theory or some kind of mythology of people choosing behind a veil of ignorance or any of the other sort of theoretical constructs that the theorists have created. And if you think about it in those terms, I don’t think that it means that the progressive excesses are not tied up with these liberal institutions. I think what it means is that there are certain tensions that are just built into our human condition that we have to manage and deal with as they take on different guises over time.

I have long thought that a good working definition of American conservatism is that it is the enterprise of conserving our political inheritance from the founders—which, as conservative thinkers (preeminently Burke) have always stressed, is something that requires an enormous amount of labor against the silent artillery of time.

MF: We’ve digressed a bit from National Review’s history. I want to return to that and think about where the magazine is positioned today. When National Review was founded in 1955 it was very nearly alone as a conservative journal of opinion and therefore it was an outsider or insurgent publication in the media landscape of that period. Today that landscape is planted thick with outlets for conservative opinion—in print, online, in broadcasting and podcasts, now on Substack for individual writers and small groups. National Review has for quite some time seemed like the voice of establishment conservatism, a label or perception for which it is both respected and attacked, depending on the moment and the person. As a longtime senior editor now leading it, are you and are your colleagues conscious of a kind of responsibility at National Review for the shape and direction of American conservatism? Is there sort of a burden of history on you guys?

RP: I think that we are mindful of the influence that National Review has had, and that it continues to have, and we want to use that influence as well as we can, and to conserve it at the same time. It is a very different situation from the one that Bill Buckley confronted in 1955. You know, there is this vast conservative enterprise now; it’s kind of hydra-headed. But the basic need is, first, to think about the circumstances in which we find ourselves and how to apply conservative principles to them—or a conservative disposition, if one prefers—and second, how to build a coalition that is large enough to take these ideas off of the shelf. Those things are still true, still challenges.

MF: There’s a sense in which, if someone showed up on my doorstep, kind of innocent of what conservative politics looked like in the United States, I think I would naturally point him toward National Review and say, well, look there, watch those guys. There’s a sense in which National Review is both many voices, and a voice.

RP: Yeah, right.

MF: Sometimes you see on the left, someone will notice an opinion by one writer on the website, or in the magazine, and they’ll say “National Review has come out for X or come out against X” or has said this or that thing.

RP: Right, yeah, so a misreading of one article by Kevin Williamson [ed. note: with NR at the time of this interview, now with The Dispatch] becomes the entire worldview of everybody at National Review. I do think, although of course there is a lot of competition, we do some things that are distinctive, that nobody else does. There is a kind of ambition to comprehensiveness that you don’t see from other publications on the right. We’ve got editorials that try to cover everything under the sun, and we try to bring the best arguments and the best prose that can be mustered. And different publications have different emphases for all kinds of reasons; a lot of them don’t have editorials, for example, whereas we take our editorials pretty seriously—without, hopefully, lapsing into self-seriousness. The Wall Street Journal editorial page is, in some ways, quite similar to us. They have, in many respects, a similar worldview, but they’re not as socially conservative or culturally conservative as we are, and they don’t stand in relation to American conservatism in quite the same way we do. They are much more, in their self-conception, I think, a voice of business conservatism.

MF: Yes, that’s a notable difference, and I think it shows up most especially in the lapses or deviations of the Journal editorial page from social conservatism.

RP: And at the same time, their view of economic issues is going to be, let’s say, a little more something that can be sort of deduced from first principles, whereas we’re, at least in principle, more willing to entertain government interventions, if they are pragmatic and sensible.

MF: Yeah, there’s a there’s a sort of reflexive libertarianism in the Journal on that front. I think, for instance, of your own work on family policy, child tax credits, that sort of thing, and the Journal thunders about this sort of thing, as you know, government handouts, and the deleterious effect on the budget worries them . . .

RP: They ran an op-ed a couple years ago and it was just about that, in which I believe they compared kids to pets and were saying, you know, you’re not going to create a tax credit for Fido, why should we be doing this? I do think that this argument has, I guess like a stray, run away from them a little bit.

MF: Well, that leads pretty naturally into my next question, which is about the shape of the present-day American conservatism that National Review has long played a role in shaping. The growing influence of the magazine over many years, decades ago, stemmed in part from its being the home of fusionism. Frank Meyer was most famously the advocate of this. It certainly has intellectual elements to it, ideological elements to it, but in practical terms—in coalition-of-faction terms—the Meyer–National Review fusionism could be said to be the cohabitation of economic conservatives, exponents of the free market, and libertarians; social and religious conservatives concerned about the country’s moral condition; and Cold Warriors, hawks, and national security conservatives chiefly concerned about foreign and defense policy, and this, especially in the era of Soviet Communism. With the end of the Soviet Union, though, thirty years ago—the threat of which might be said to have united the elements in fusionism—conservatism has fractured into various factions that seem to be at odds with each other almost as much as they are with the left. So my next question is what, if anything, serves as a force for unity today? Is it simply as low and crass as the binary character of our partisanship such that conservatives tend, by nature, to vote Republican? Does that often reduce itself simply to “not the Democrats, by God!”? What is it that holds together conservatism today?

RP: I think that conservatism is often reactive. I think it was Samuel Huntington who said that it’s a strange beast that hibernates through the summer and awakes in the winter. It comes to the defense of embattled institutions and ways of life and it in a way doesn’t pick its battles, because it finds the site of conflict and then responds. We are now at a moment when American institutions are embattled. There is a lot of criticism and not constructive criticism at the margins, but really destructive, corrosive, foolish, and nihilistic criticism, mostly from the left, sometimes from the right, of our entire political order, of our Constitution and of the basic ideas and dispositions on which it rests. And I think that the bulk of conservatives instinctively respond negatively to those attacks.

Now, I think there’s a great deal of contestation and dispute about what an effective defense would look like. Does contemporary conservatism need to move further away from economic libertarianism in order to preserve our way of life? Does our foreign policy need to be more restrained? What should we do about Apple and Facebook? These are all practical questions that divide conservatives. I think that those lines of division are bigger than they were in, say, the 1990s and the early 2000s, maybe in some ways smaller than they were in the late 1950s, but I do think this is a moment to have those arguments, hash them out, and come up with a new synthesis that might be able to command a broad consensus among American conservatives.

I also think it is possible to exaggerate the extent to which the basic fusionist formula has been extinguished. It’s interesting that we’ve managed to come this far in this conversation without saying the dread name, but Donald Trump’s victory in the 2016 primaries and everything that came after it have often been held out to be a kind of defeat or death knell for fusionism. But if you think about what his administration actually did in office, and particularly about the things that it did that were successful, I think you can see a pretty strong fusionist influence. I think, arguably the three greatest accomplishments were a tax reform that could have been and basically was written by Paul Ryan, a reform of the judiciary that was superintended by Don McGahn and the Federalist Society, and the defeat of ISIS. These are all elements of a fusionist conservatism. You can think of other things that he did that fit the mold less: I would say, for example, the tariffs on China. I’m not against the idea of ever imposing a tariff on principle, but I don’t know that the kind of spastic protectionism in which he engaged was actually successful. It seems to me to have a lot of debits in the ledger and not a lot to show for it.

I think it is possible to exaggerate the extent the extent to which the basic fusionist formula has been extinguished.

MF: Well, it’s interesting, I was going to come to Trump next, actually.

RP: All roads lead to Donald.

MF: Well, let me back up for just a second. I have not heard that Samuel Huntington quote before. That definition of the conservative as the beast that hibernates in summer and wakes in winter—that’s an interesting image. I mean, what are conservatives but people who look about them at the existing state of affairs and see goods worth preserving? They may look with some regret, perhaps an undue nostalgia at things already lost that they would like to resuscitate or revivify in some way. That does make conservatism somewhat reactive. The fights in which it engages are more often than not brought to it by progressives who are trying to engineer change—sometimes changes no one imagined five minutes ago, like our present fights over transgender ideology. No one, hardly anyone ten years ago was worrying about that, and now it’s on everyone’s radar screen.

And of course the rap on conservatives, for precisely this predilection of theirs to prefer the status quo, is that they’re simply opposed to change as such—that they are nostalgia merchants, or reactionaries, or defenders of illegitimate elements of our present condition. I guess you would probably agree that that’s a bum rap, but it’s also the case that conservatives must beware of their own prejudice against change. I think, for instance—I was reminded by Continetti’s book of this—of National Review’s, and specifically Bill Buckley’s, later-abandoned view in the 1950s that the civil rights movement and Brown v. Board of Education were dubious projects of reform—and that the white power structure in the South in some sense had a claim on our respect for a status quo that seemed to work, for their part of the country. That, I think, was later confessed by Buckley himself to have been the wrong position to take, but it represented the potential downside of conservatism, which is to stand pat on what is when change would be preferable. You agree with that?

RP: Buckley brought the various strands of conservatism together, and in this case, you can bring together originalism and support for federalism and preference for markets and a hostility to radical change, and they all converged and yielded the wrong answer to the question. There was a lively debate inside National Review, I don’t wish to flatten it. But yeah, these were real conservative tendencies that were tragically misapplied and wrongly applied in this situation, which demanded something close to revolutionary change—albeit change that was also a vindication of principles that had always been there in the Constitution. And there was, I should also add, some totally crazy stuff in the magazine over the years, you know, like the attempt in some cases to argue that the Fourteenth Amendment was illegitimate, for example, which is, in a way, a trying to square the circle that just couldn’t work.

MF: On the positive side of the ledger, there was Buckley’s decree—I think it can be characterized as a decree—that no one could write for National Review who wrote for the American Mercury when it came to be the vehicle of anti-Semitism. So the magazine had no truck with anti-Semitism. And set its face against the John Birch Society, although that took a little time since the Birch Society, although almost forgotten today, really did have a good deal of clout in this country sixty years ago. And while the magazine has always been open to libertarians and it’s not closed its doors on those who espouse a fondness for Ayn Rand, Rand herself was roundly condemned in the late ’50s in a famous book review of Atlas Shrugged by Whittaker Chambers. So, in a sense, National Review has been, again on the positive side, a salutary gatekeeper or boundary keeper for what counts as respectable conservatism in this country. It’s not Rand’s espousal of free markets that bothered anyone, it was the sort of Nietzschean atheism.

RP: Yeah, of a particular militant sort. Those debates have their echoes today. The last six years of our politics being what they have been, a lot of this has become a question about whether you are pro-Trump or anti-Trump enough. And it’s interesting to me that there are people who have roots in the right, or consider themselves conservatives, who attack us for being too pro-Trump or not hostile enough to him, and then there are people who attack us for being too anti-Trump or not enthusiastic enough about him—and in both cases they use identical phraseology and call us “Conservatism, Inc.” To be fair, I think that they are picking up on something that is real, that there is a sense that there is a kind of mainstream conservative opinion. We’re not going to be in lockstep, we’re never going to be taking polls before we take positions, but our broad attitude of having serious reservations about Trump, appreciating many aspects of his presidency and then having a range of opinion within that broad formula, I think that that speaks for most American conservatives.

MF: That’s a very good segue into my question, which is kind of Trump-related. There’s long been a populist or anti-elite strain in American conservatism, and Donald Trump certainly rode, and perhaps conjured, the most recent wave of that populism—a populism that can be found in earlier generations, led, for instance, by Pat Buchanan and others. National Review, early in the 2016 primary season, ran an issue with the two words “Against Trump” on the cover and it was sort of a theme issue that had a chorus of voices opposed to him. That, of course, did nothing to stop Trump, who went on to win both the GOP nomination and the presidency. Over time, in the Trump era, the magazine and the website became home to a diversity of voices on “The Donald,” from staunch opponents to cautious supporters. I don’t know that that I can think of any full-on enthusiastic supporters of Trump who have been regular writers for the magazine or website, but the editorial voice backed many of his administration’s policies and its appointments. You mentioned his tax cuts, his judicial appointments. But we’re now in a post-Trump era—or post-Trump I, if he makes a comeback.

RP: I aspire to be in a post-Trump era.

MF: Well, that lays down a marker. On balance, thanks to this populism that he brought to the front rank of the conservative parade, where would you say the mainstream of conservatism is located now after the Trump presidency? How did it change thanks to him?

Where I hope conservatives will land is with an agenda that is populist in the sense of speaking for tens of millions of people and responding to the needs and challenges that America has today and in the near future, and that is rooted in our conservative dispositions toward tradition and subsidiarity and the work ethic, and so forth.

RP: I think that Trump was better and more effective at destroying an old conservative program or formula than at fleshing out something new. He was not especially interested in the latter task, or perhaps especially gifted in performing it. That wasn’t where his political talent lay. And that’s one of two reasons why I think things are up for grabs.

The other is that arguing about Trump, and getting sucked into the vortex of his personality, has been a kind of substitute for having arguments about those other issues. And so he destroyed this old order, didn’t replace it with something new, and then by his being sort of paralyzed conservative thought. So you had some interesting assertions, but I don’t think you ever have had a healthy debate and you’re probably not going to until we move to a post-Trump world. But I think that there are lots of interesting disputes to be had, and I can say where I think it is possible that conservatives will land, and where I hope conservatives will land is with an agenda that is populist in the sense of speaking for tens of millions of people and responding to the needs and challenges that America has today and in the near future, and that is rooted in our conservative dispositions toward tradition and subsidiarity and the work ethic, and so forth.

I think a lot of work has to be done to make that more than just a vague wish. Some of it is being done, but there’s a lot more to be done. Trump did a little bit of it or people he employed did a little bit of it, but not a lot, frankly. And so we will not lack for work opportunities in the near future. On foreign policy, I think that that means that we are trying to figure out a way to—what’s that phrase—to create “a balance of power that favors freedom.” I don’t think that we should have a crusading foreign policy that attempts to spread democracy and markets by force of arms. But I do think that we have a stake in the basic peacefulness and prosperity of the world, and can’t realistically—and shouldn’t try to—retreat behind our borders.

In trade, I think Trump leaves us with a stronger protectionist wing of the Republican Party than there used to be, where protectionist arguments are going to be treated, in discrete instances, with respect, not simply booted out of the room. But I don’t think that those arguments have carried the day completely, nor will they. I suspect that that means that we’re probably not—not just conservatives, but anyone across the political spectrum—going to be aggressively liberalizing trade. But you know, the sort of idea that Trump floated once or twice in his presidency of a 35 percent tariff on everybody—I don’t think that that has taken over the Republican Party or the public at large, by any means.

Immigration, I think, is an issue where Trump weirdly ended up being on all sides of every aspect of that issue. I don’t think that the Republican Party is going back to George W. Bush’s enthusiastic embrace of broader immigration any time soon, but I also don’t think that we are going to be the party of an immigration moratorium or of family separation at the border. There’s obviously a huge space in between those positions for sensible and intelligent policy, and I think National Review is going to be among the many people who will try to articulate what that should be and then defend it.

MF: You know, I think the events of January 6, 2021, cannot be ignored in an assessment of Trump, and notwithstanding the events of that day, he still has a strong base in the GOP and he’s talking about running for president again, and persists in his claims that the 2020 election was stolen from him. And there is a surprising, perhaps dismaying number of people in the GOP base who share his view of that. Is there a sense in the editorial councils of National Review that Trump should be opposed, now and permanently, owing in part to those events? Or is there a feeling that, well, maybe we have to keep our powder dry, since he may wind up being leader of the party once again?

RP: I think there’s a broad consensus within the magazine that Republicans and conservatives should be looking for somebody else as a political leader in 2024, partly because of January 6. And partly because he lost in 2020, right? I mean he lost to somebody who was not an especially compelling candidate, Joe Biden, who was on his third try for the presidency, arguably fourth if you take the idea that he was running in ’84 seriously. That was a winnable race, too, in 2020, that he squandered largely because of his personal failings and the public’s revulsion against those personal failings. So I think that we could have a leader who would not be perfect, but would be superior in character to Trump, whose character wouldn’t raise the practical problems that Trump’s repeatedly did, and who would be more effective, both at winning the 2024 election and then at governing thereafter.

MF: And being eligible for a second term to follow.

RP: And also, that’s right, yes, being eligible to run again in 2028. So I think there are differences of degree, but yes, I think that I would speak for all of us in saying we should be looking for another candidate.

We could have a leader who would not be perfect, but would be superior in character to Trump, whose character wouldn’t raise the practical problems that Trump’s repeatedly did, and who would be more effective, both at winning the 2024 election and then at governing thereafter.

MF: Let me turn to some brighter prospects and good news, recent very good news. The Dobbs ruling in late June was a great triumph for the pro-life cause and for constitutionalism—both things championed by National Review and particularly by you, as long ago as your book The Party of Death. Where do we go from here on both these fronts—on the cause of life and on the cause of constitutionalism? And I mean, perhaps we should pause for a moment and thank Donald Trump and his allies in the Federalist Society for giving us the Supreme Court majority that could accomplish this victory, but where do we go from here on life and on constitutionalism?

RP: Yes, we should, we should pause and express gratitude toward Trump. I would say, also, to so many people, living and dead: Ronald Reagan, Henry Hyde, Bob Casey Sr., Mitch McConnell. But I will especially say Trump because, you know, I was one of those who in 2016 expressed great skepticism that he would follow through on his new pro-life commitments and—

MF: I’m guilty as charged on that as well.

RP: Yes, so he definitely was a very pleasant surprise to me on that front and that should be acknowledged, you know, notwithstanding all the other criticisms that I make of him, and that I stand by making of him. In terms of what comes next, let’s start with the pro-life cause. I think that it becomes a multi-front struggle. I think that we’re going to have to stave off federal legislative action to enshrine something akin to Roe v. Wade, and if we fail in that, although I think we’ve got pretty good prospects right now, then we’ll have to undo that as well.

In the states, we have to fight for the maximum feasible legal protection for unborn children that can be sustained over time, and that is going to vary from place to place and time to time; and at the same time, we’re going to have to constantly strive to expand the boundaries of what the maximum feasible protection that can be sustained over time is, through the hard work of persuasion, which was in some way stifled by the long reign of Roe v. Wade.

That also should include both private and public sector action to make our society more welcoming of life, whether it means change in our economic policies so that they are better for families, or expanding our support for crisis pregnancy centers that try to tend to the needs of both babies and their parents.

There is quite a lot of work to be done, and I remember, many years before Dobbs, wondering whether pro-lifers would understand, given the great deal of misconception that had been spread about what Roe v. Wade meant—I had worried that pro-lifers might not appreciate how much work would remain to be done after Roe was overturned, but I think that there is a good deal of realism, maybe in some places a little bit less than I’d like, but a real understanding that this is the time to redouble our efforts.

A real constitutionalism, I think, can’t be as court-centric as ours and everyone’s have been. We need to have a recovery of a legislative constitutionalism and an executive constitutionalism as well.

In terms of constitutionalism, I think that there’s a different kind of a multi-front battle. There’s still quite a lot of work to be done in the courts, and in the intellectual world of legal conservatism. And I think that there are some temptations to be avoided as well.

So much of the arguments lately about the possibility of conservative overreach on the Court has concerned whether the conservative majority on the Supreme Court will be too eager to overturn precedent, and particularly social-issue precedent. I think that where they could potentially go too far instead is in a kind of libertarian economic activism in striking down democratically enacted laws based on theories of the right that have been cherished more than they have necessarily been examined. Which is not to say that I’m against any possible revival of the nondelegation doctrine, for example, but I think that that we need to be careful about that, and shouldn’t have ambitions of sort of overturning the Great Society and the New Deal from the bench.

Which brings me to the other part of the struggle, which is that a real constitutionalism, I think, can’t be as court-centric as ours and everyone’s have been. We need to have a recovery of a legislative constitutionalism and an executive constitutionalism as well. The idea that the Constitution is in some way the property of the courts has also meant that they are in practice not the responsibility of other branches of the government, and we need to restore the sense that they are in fact their responsibility.

MF: You know, lately, the past couple of years there’s been a sort of insurgent faction on the right critiquing originalism for its failures. And Dobbs seems to be a vindication of originalism. I know that there are some who look at the Dobbs opinion of Justice Alito and say that they don’t see much originalism in theoretical terms in it. But the abandonment of the twentieth century’s most constitutionally and morally disastrous ruling cannot be otherwise than a victory for the original understanding of the Constitution, it seems to me.

It seems, therefore, to be a setback for certain conservatives who take a critical posture toward originalism. I’m sure those arguments are going to continue; they’re mostly arguments that take place in academic settings, where, of course, the exponents of the arguments have the leisure to carry them on even in the face of events. But I think that the contribution of Dobbs and of some other recent rulings is to make some headway on just that front that you closed in mentioning a moment ago, which is that the judiciary is not the owner of the Constitution, nor is it the proper venue and the proper engine for social change. Dobbs, of course, does not outlaw abortion. Dobbs is not a seizure of power by the Supreme Court. It’s quite the opposite; it’s a relinquishing of power unjustly usurped for half a century. I think anything we can do to encourage more of that kind of decision-making, of the Court withdrawing from great swaths of territory that it has unjustly occupied like an invader, is all to the good.

RP: There’s a lot to discuss in that comment. I would say, first of all, with respect to whether Dobbs is an originalist decision: I think of it a little bit like the constitutional requirement that Congress declare war. It doesn’t mean the Congress has to pass legislation that uses the exact words “we declare war.” That means that if you have a war it has to be authorized by Congress. And it doesn’t have to use that verbiage to accomplish that task. I think you can have an originalist decision if the result is a constitutional law that is more in keeping with the provisions of the Constitution, as originally understood by the informed ratifying public, and that is attentive to our legal history. And the fact that Alito did not do a ground-up reconstruction of the historical meaning of particular provisions is, I think, not really a fault of the decision. The decision arose in a particular context, and it does apply the provisions of the Constitution, as originally understood, correctly.

MF: It answered the questions that were necessary to answer to decide the case.

RP: That’s right; it’s not a theoretical exercise. For one thing, he’s answering the questions that the parties brought. Neither party ended up asking, “Hey, can you come up with some way to split the difference on Roe v. Wade that has some basis in the Constitution if you squint really hard?”—which is the question that Chief Justice Roberts decided to take up. And neither said, “Could you weigh in on what’s right and what’s wrong in the last 70 years of court precedent having to do with privacy, social issues, or sexual morality?”—right? So Alito decided what was in front of him, and I think he decided it quite well.

Over the years, I know you’ve had some criticisms of other originalists—I mean originalism is a kind of fractious enterprise in itself—and I have as well. I wasn’t sure that Shelby County was correctly decided, for example. But I think of the Federalist Society as an example to be emulated across the world of conservatism rather than as something that has gone wrong with conservatism. And I think that the critics of originalism on the right vary in their cogency and their candor, but they do tend to think of the Federalist Society as a kind of project that has either failed or is in some sense malignant. And I just reject that. I think that the mainstream of judicial conservatism has been much more right than wrong.

MF: A last question and we’ll wrap up. You came to National Review yourself as a very young man, and you rose quickly to being one of its most visible writers. As the magazine and the website have added staff—it’s a big operation now, doing a lot of shoe-leather reporting, as well as opinion journalism—and National Review has continued to launch and to foster the careers of young conservative journalists, what is your advice to young men and women in college or even in high school today who want to make their work and make their mark as reporters and opinion writers in the conservative movement and conservative media?

If you are thinking of having a writing career in journalism, it’s never too early to start learning how to work with editors, and getting published different places and thus getting noticed by other editors far and wide, learning how to take edits, even sometimes ones that might appear to you to be foolish.

RP: I think you should read widely. You should read non-conservatives, because I don’t think you should make your life’s work just knocking down the dumbest and weakest examples from the other side. You should also read widely just to acquire a better prose style, which will not involve trying to be the next William F. Buckley, Jr. or the next H. L. Mencken, but being somebody who can appreciate the rhythms of their prose and can create something of your own that makes sense for you.

If you are thinking of having a writing career in journalism, I think it’s never too early to start amassing clips for a variety of publications, learning how to work with editors, and getting published different places and thus getting noticed by other editors far and wide, learning how to take edits, even sometimes ones that might appear to you to be foolish.

MF: And to hit a deadline.

RP: Right. And I would say, also sometimes young people get the advice that they shouldn’t try to be pundits, because nobody’s interested in what their opinions are. And I think that’s a little bit of a mistake, because I think that the truth of it is that nobody wants them to become bad pundits. But if the expression of their opinion is backed by argument and fact, and fresh prose, and is not just a pure expression of opinion, then I think it’s very worthwhile. But that may be something that you cultivate over time, or that you grow into rather than something that you start out with.

MF: That’s good advice. I’ve recently retired from forty years of teaching young people in college, and I can’t tell you how many times students approached me with trepidation and wondered if their opinion was all right in the paper they were writing for me, and I’d say, “All right? It’s the thing I want the most, because I want your argument about the significance of these matters we’re discussing. I want your judgment about what is right and wrong, what is just and unjust, what the facts are and what they’re not.” So yeah, I think it’s bad to tell young people who aspire to be journalists, “don’t try to be a pundit.” Try to be a good one! But that means, I think, trying to find out some things that others don’t know that you can tell them, trying to analyze those things so as to make their importance evident to others, and then to make some judgments about those things that if they don’t persuade everyone at least have the quality of being a good-faith effort.

RP: That’s right, it seems to me. When people ask me what opinion journalism is, I think the implicit question is, what distinguishes it from propaganda? And I think that the answer is that the good opinion journalist will make admissions against interest. You will acknowledge the complexity of human life, which does not mean abandoning a position or not arguing for it strongly, but I think adds to your persuasiveness doing so.

MF: All right, well, I think we’ve spoken for a little over an hour and I thank you for your time. Thanks for agreeing to do this.

RP: I’m going to also confess one flaw for now of National Review that I would like to rectify, that there is not enough Matthew J. Franck in it.

MF: Well, thank you, I appreciate that very much. I’ll try to do something about that. I owe you that much, and thanks for being with me today.

RP: Thanks very much.