In lectures before he became Pope Benedict XVI, Joseph Ratzinger argued that politics, rightly understood, focuses on concrete steps that citizens take in the present, not idealistic dreams for the future. He worried that political messianism seeking to grasp a perfect world would obstruct “all rational political activity aimed at the genuine amelioration of the world,” and cautioned that “the future is an idol that devours the present.” On another occasion, Ratzinger named “the inability to be reconciled with the imperfection of human affairs” as one trend leading to the repudiation of democracy: “The demand for the absolute in history is the enemy of what is good in it.” He counseled:

[T]he continued existence of pluralistic democracy (that is, the continued existence and development of a humanly possible standard of justice) urgently requires that we have the courage to accept imperfection and learn again to recognize the perpetual endangerment of human affairs. Only those political programs are moral which arouse this courage. Conversely, that semblance of morality which claims to be content only with perfection is immoral. Those who preach morality in and near the Church will also have to make an examination of conscience in this regard, since their overwrought demands and hopes aid and abet the flight from morality into utopia.

Christianity, rightly understood, leaves politics in the realm of ethics and makes it possible for us to accept imperfection in the City of Man. Because man remains free and begins anew in every generation, each generation must struggle to establish a right form of its society. Hence politics, especially Christian politics, is concerned with the present and not the future, even if it hopes to build enduring institutions.

To give a more concrete example of how Christians should engage in politics, Ratzinger ended with a then-contemporary conflict in Poland over whether the Marxist state would permit crucifixes to be hung in schools. He characterized this as a conflict over “the public character of Christianity” and therefore over the substratum of fundamental values that just states need in order to flourish (a theme to which he would return during his pontificate). “The state needs public signs of what supports it,” he argued, and therefore Christianity must insist on public signs such as festivals or crucifixes. He then added: “But of course it can insist on them only if the force of public opinion supports them. This presents a challenge to us. If we are not convinced and cannot convince others, then we have no right to demand public visibility, either. . . . The only strength with which Christianity can make its influence felt publicly is ultimately the strength of its intrinsic truth.”

Start your day with Public Discourse

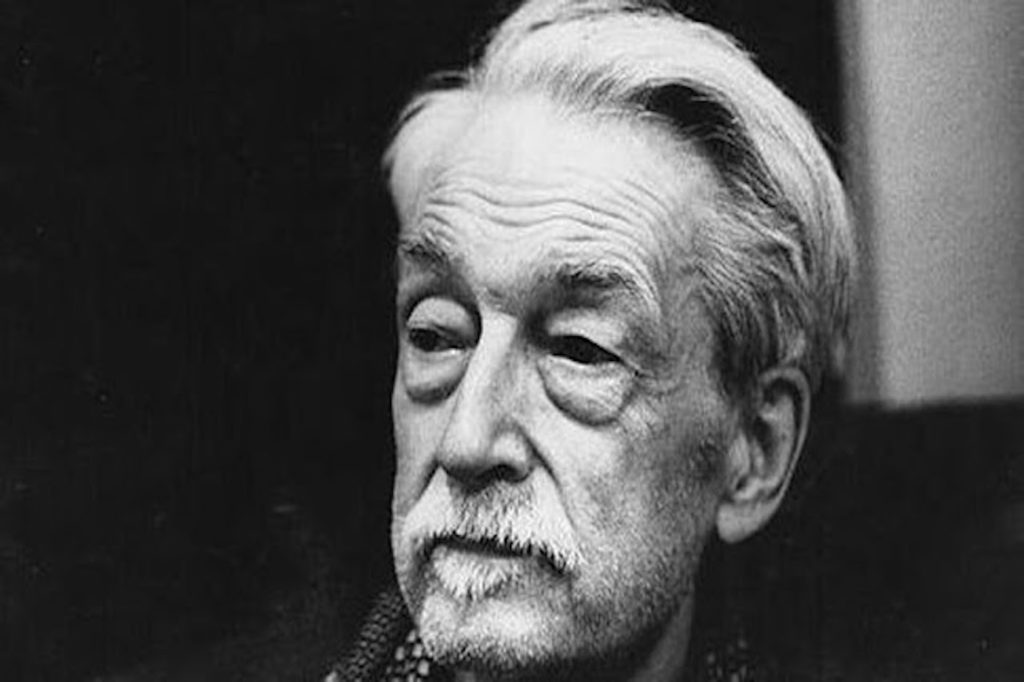

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.The focus on concrete action in a messy present over dreams of a more perfect tomorrow; the desire to provide a right foundation and justification for pluralist democracy, which is seen as a good form of government, perhaps the best; the need to guide human freedom without demeaning or diminishing it; the Church making her influence felt through the strength of truth, not political coercion without popular support: more than any other single thinker, Jacques Maritain articulated this vision of Christianity and politics, which Benedict, John Paul II, and other post-conciliar popes came to embrace. In texts such as The Primacy of the Spiritual, Integral Humanism, and Man and the State, Maritain laid out in an almost prophetic way how most Catholics think about church, state, and the role of Christian laymen in modern democratic societies. Then in The Peasant of the Garonne, written immediately after Vatican II, he announced that his project was a failure: the Church was too busy kneeling before the world to call it to kneel before Christ.

As many Catholics reconsider their instincts about the Church and its relationship to the liberal order, we would do well to return to Maritain. Despite his limitations, he still offers us essential principles for how to engage in politics—at least the politics that Ratzinger claims are proper to Christianity.

Essences, Existents, and a New Kind of Christendom

Maritain’s first foray into political philosophy, The Primacy of the Spiritual, was written in the wake of Pope Pius XI’s condemnation of the French traditionalist political movement Action Française, of which he had been a member. His immediate task was explaining why French Catholics should take the condemnation seriously, how it was a just use of papal power, and on what grounds it was made. He relied on the theological distinction between the church’s direct power, by which it directly governs the faithful in matters of faith and morals, and its indirect power, by which it intervenes in temporal affairs for the sake of spiritual matters and the preservation of its own liberty. Since spiritual matters are higher than temporal ones, the Church’s spiritual jurisdiction is higher than the temporal jurisdiction of the state. Therefore, the Church has the right to intervene and advise in affairs of state when they pertain to the spiritual matters under her jurisdiction. By this logic, even if he would not normally intervene in French politics, Pius XI was justified in condemning a political movement for subordinating religion to politics and thereby endangering the souls of the faithful.

Maritain argued that core theological principles remain the same over time, though they exist in different ways depending on the historical conditions of different ages.

Maritain was convinced that the principle of the primacy of the spiritual was still true 600 years after its famous exposition in Pope Boniface VIII’s bull Unam Sanctam. But he was also convinced that the sacral politics of medieval Christendom were over, and not coming back. To explain how to understand enduring theological principles in different periods of history, Maritain turned to Thomistic metaphysics. Aquinas distinguishes between the essence of a thing (what the thing is) and its existence (the actualization of the thing’s essence in a particular instance). The essence of dog exists in a particular way in this dog, Spot. By analogy, Maritain argued, core theological principles are essences that remain the same over time, though they have existence in different ways depending on the historical conditions of different ages.

The three principles that best fit this description were the freedom of the Church to preach and teach, the primacy of the Church over the body politic or the state, and the necessary cooperation between the two. For example, the freedom of the church in the time of Thomas Becket might mean that the state must respect the Church’s desire to try clerics in ecclesiastical courts, not hand them over to civil ones. But it is not necessarily a violation of that principle for the Church to support the state when it prosecutes twenty-first-century priests for sexual or financial crimes.

This distinction between essential principles and their historical existence was similar to the difference between the “thesis” and the “hypothesis” that many theologians used to account for the discrepancy between the Church’s teaching in theory and how it could be implemented in a particular society. In the American context, for example, the thesis was the principle that the state should acknowledge the Catholic Church as the true teacher of faith and morals in law, while the hypothesis was the reality on the ground that prevented that principle from being implemented—for now. The European confessional state remained the ideal model; if the circumstances changed, the primacy of the Church must be realized in the New World as it had been in the old.

Maritain acknowledged that the “thesis” and “hypothesis” framework could be validly used, but claimed that its roots did not run deep in theological tradition. Moreover, it was frequently used as a univocal concept, one in which the same principle should be applied immutably despite changes in historical circumstances. He judged that “such a univocal construction does not take into account the intrinsic reality as well as the intelligible meaning of time.” The idea that a supra-temporal ideal would be applied in the same way in different temporal circumstances was self-contradictory, since such applications take place in different ages and are therefore relative to those historical circumstances. The univocal conception of thesis and hypothesis risks mistaking the contingent historical applications of principles for the eternal principles themselves. And applying principles in our time as they were in the past—trying to force medieval Christendom on a modern democracy—would mean employing a violence that would betray them.

Rather, Maritain argued that “the application of the principles is analogical—the more transcendent the principles, the more analogical the application—and that this application takes various typical forms in reference to the historical climates or constellations through which the development of mankind passes; so that the same immutable principles are to be applied and realized in the course of time according to typically different patterns.” As Joseph Evans puts it, “For Maritain, political beings, that is, political societies are political beings analogously—they exist in ways that are only proportionately the same. Consequently, if the guiding principles are immutable, due to the immutable essential and hierarchical structures of man and the universe of being, their realizations and applications in different political beings are analogical, due to the different existential situations.” The principle of analogy thereby protects truths about God and man that do not change, while accommodating contingencies of history and the fact that our understanding of those truths can deepen over time.

This was a concrete question Maritain faced, especially in response to Catholics who maintained that medieval Christendom was the enduring blueprint for a society. As he was writing Integral Humanism in the mid 1930s, Maritain received a copy of a magazine published by a group of young Catholic Nazis, who were disciples of Carl Schmitt. It contained a book review criticizing him for claiming that the Holy Roman Empire was an out-of-date ideal—not bad in itself, but a thing of the past and therefore unsuitable as a political goal for the present. “Is it because he is a Frenchman that Maritain speaks in this way,” the young writers asked, “or is it for some other reason?” Maritain replied: “If I speak in this way, it is because I know the dangers of a univocal conception of the Christian temporal order, which would tie the latter to dead forms instead of assuring the living tradition of the work of the past.”

What Maritain sought was a new kind of Christendom, something between the naked public square of secular liberalism and the confessional state of times past, something animated by Christianity but realized in our own time. Already in The Primacy of the Spiritual he wrote: “Under the historical sky of the Middle Ages the Primacy of the Church or Truth could and ought to be achieved by the exercise of the rights of the spiritual power. Now that is realized by the moral authority that the religiously divided world will come to acknowledge in the Church.” Maritain believed that religious division was a misfortune, but also an obvious fact of modern life. For us, the body politic is more clearly distinguished from the spiritual realm of the Church and is now founded on a temporal common good in which citizens of different beliefs share equally.

Maritain sought a new kind of Christendom, something between the naked public square of secular liberalism and the confessional state of times past, something animated by Christianity but realized in our own time.

Maritain saw this not as a concession to secularism but “a development of the Gospel distinction between the things that are Caesar’s and the things that are God’s.” The historical circumstances had changed and clarified how we might better live out the primacy of the spiritual. This change impelled the Church to influence society less in terms of social power and more in terms of “vivifying inspiration,” a mode more appropriate to the Church’s superior dignity and detached from that of the Constantinian age. Now this dignity and authority could be conveyed not by the coercion exercised over the civil power, “but by virtue of the spiritual enlightenment conveyed to the souls of the citizens, who must exercise judgment, according to their conscience, on every matter pertaining to the political common good.”

In previous ages, Maritain wrote, “the supreme principle that the political society has obligations towards truth, and that its common good implies the recognition, not in words only, but in actual fact, of the existence of God,” was implemented by monarchs from the top down. In our own time, it must come from the bottom up and be implemented by the people freely acting according to their own consciences. Preaching and living out the Christian faith were therefore all the more imperative for persuading a free people of its truths, and for reviving “the often unconscious Christian sentiments and moral structures embodied in the history of the nations born of the old Christendom.” And the principle of the cooperation between Church and state would see the integration of Christian work into the temporal life of society. Christian teaching would have its place in educational life, and the state would ask religious institutions to help provide social assistance. In this way, “the mode of activity most proper to the eternal city, namely, spiritual and moral activity, then becomes the dominant mode in the collaboration of the two powers.”

Justifying Beliefs and Practical Conclusions in Political Action

In a sacral society, rulers made decisions that—in theory—had their ultimate justifications in theological principles. In a pluralistic democracy, political action requires agreement on practical principles, which comprise a civic or secular creed—in a free democracy, “the creed of freedom.” These include principles such as religious liberty and justice between equal persons and between them and the body politic. On the one hand, Maritain is at pains to claim that this creed is not the indifference of bourgeois liberalism or a completely neutral marketplace of ideas. Nineteenth-century bourgeois democracy was “a neutral, empty skull lined with mirrors,” and was therefore swept away in many countries by the totalitarianisms of the twentieth century. On the other hand, he is clear that the civic creed of democracy does not belong to the spiritual order but the temporal one: “The faith in question is neither an authentic religious faith nor a spurious religion and caricature of spiritual values like Rousseau’s ‘religion civile,’ a minimum of originally religious belief which has become secularized, emptied of its substance, and imposed on all in the name of the people or of the State. It is a temporal or secular faith, bearing on the essential tenets of life in common in the earthly city—its motivation is human, and human its object—it is in no way a religious faith.”

Perhaps the largest-scale example of this came with the drafting of the UN Declaration of Human Rights: those who drafted and ratified the declaration could agree on the rights it enumerated—a temporal faith—though they disagreed about the justifications for those rights in different creeds or philosophies. Likewise, in particular societies our justifications for democratic principles may vary. The state’s task then is not to impose one creed or set of justifications on its populace, but to sustain that creed by education, including in the many justifications that might be given in any particular society. Adhering to particular schools of thought belongs to the freedom of each person, but democracy could not survive if it were “severed from the roots that give it consistency and vigor in the mind of each individual, and if it were reduced to a mere series of abstract formulae—bookish, bloodless, and exanimate.” The democratic civic creed is a living creed and must be preached and lived as such. This would of course entail teaching those religious traditions that are part of the body politic’s heritage and that serve as the roots of our democratic order; to neglect them would “simply mean for democracy to sever itself, and the democratic faith, from the deepest of its living sources.”

That deepest living source is Christian faith, as Maritain recognized. The UN Declaration’s enumerated human rights could be supported with differing justifications, but the best justifications were found in Christianity. Maritain’s confidence in the democratic civic creed depends partly on the necessities of our common human nature, and partly on perceptions of the heart “awakened by the Gospel leaven fermenting in the obscure depths of the movement of history.” The global spread of the gospel—and the dominance of the European culture it inspired—allowed for a global conceptual language for topics such as human rights.

Maritain himself writes that the democratic charter “has taken shape in human history as a result of the Gospel inspiration awakening the ‘naturally Christian’ potentialities of common secular consciousness, even among the diversity of spiritual lineages and schools of thought which are opposed to one another, and sometimes warped by a false ideology.” Christianity therefore provides the deepest and best foundation for the democratic creed. The more a people is imbued with Christian convictions, the more it would adhere to the secular faith of the democratic charter, and the more the Christian philosophical justifications of the charter would be recognized as the most valid ones—not because the state adopted them, but because the people had.

Against Religious Totalitarianism

This latter point was essential for Maritain. A society in which the vast majority of its members live the Christian faith should of course be welcomed and should remain an inspiring ideal. But free modern democracies cannot make people Christian with the coercive power of the state without having them become “the inhuman counterfeit, whether hypocritical or violent, offered by the totalitarian states.” The modern democratic view of freedom marks a historic moral advance in which believers and unbelievers live together and share in the same common good. Unlike the sacral civilization of the past, the lay civilization of modern times recognizes the equality of all the members of the body politic—Christian and not—as a basic principle. The state is no longer the secular arm of the Church but the servant of an independent body politic. The Church had always taught that faith cannot be imposed by constraint, even if princes disregarded that instruction. In order to avoid the evils of totalitarianism, modern democracies need to recognize the importance of the freedom of conscience for “both the common good of the earthly city and the supra-temporal interests of truth in human minds.”

Maritain's vision promotes laws inspired by Christian morality and safeguards the freedom of non-Christian minorities, without adopting strict liberal neutrality.

This did not mean that freedom of conscience and religion was the fruit of theological liberalism or polytheism. Pluralistic democracies should still direct their citizens toward the moral law, rightly conceived, as much as prudence will allow in their particular situations. In Integral Humanism, Maritain offers a sketch of how a religiously pluralistic society could pass laws inspired by Christian moral principles. First, different religious groups would be granted a particular juridical status. Then the legislature would adapt this status to the condition of the groups and to “the general line of legislation leading toward the virtuous life, and to the prescriptions of moral law, to the full realization of which it should endeavor to direct as far as possible this diversity of forms.” The body politic would thereby be directed toward “the perfection of natural law and Christian law, . . . and its different structures would deviate more or less from this pole, according to a measure determined by political wisdom. In this way the body politic would be vitally Christian, and the non-Christian spiritual families within it would enjoy a just liberty.” Of course Maritain offers only a philosopher’s sketch, but such a system promotes laws inspired by Christian morality and safeguards the freedom of non-Christian minorities, without adopting strict liberal neutrality. Still, his sketch depended on Christian citizens who would draw on the faith that formed their society to live out their convictions.

The Breakdown of the System

Then the historical sky darkened. Shortly after Paul VI triumphantly closed the Second Vatican Council—significant parts of which were the fulfillment of Maritain’s prophetic vision—Maritain published The Peasant of the Garonne. An angry energy replaced the serenity and philosophical poise of his previous works; at times, the book reads as though Dmitri Karamazov had written a report of the Council. In 1936, Maritain had worried that “a very large part of the youth has arrived at a state of complete religious indifference, due perhaps, in part, precisely to a transfer of religious feeling to other aims.” Now he feared that large swaths of the Church had undergone a similar transfer of religious feeling, forsaking the worship of God to kneel before the world. Then he had prophesied that the theology of St. Thomas would “dominate a new Christendom.” Now the Thomistic foundation of Catholic thought was being jackhammered to pieces.

The postwar hopes for political transformation had disappeared as well. “Until today,” Maritain wrote, “the hope for the advent of a Christian politics (corresponding in the practical order to what a Christian philosophy is in the speculative order) has been completely frustrated.” His single counterexample was Eduardo Frei, the Christian Democratic president of Chile. Maritain claimed that only three revolutionaries in the world were worthy of the name: himself, Frei, and his great friend Saul Alinsky, the American progressive activist.

In his recent article at Public Discourse, Daniel Philpott outlined contemporary critiques of Maritain’s thought as better suited to the conservative Christianity of his day, excessively individualistic, or too content to keep the church a spiritual power only in the face of a hungry and hostile modern state. Another critique sees Maritain’s political philosophy as a period piece, plagued by the unfounded optimism and theological problems of the 1960s. Maritain never mentions Karl Rahner by name, but his thought drove the trends that Maritain critiqued when he condemned the spirit of the Council. One of Rahner’s best known concepts is the “anonymous Christian,” a person who lives in Christ’s grace through faith, hope, and love and possesses the Holy Spirit like any Christian—but without explicit knowledge of or belief in Christ. Some have claimed that Maritain’s project was effectively an “anonymous Christendom” in which the democratic faith inspired by Christianity replaces the explicit profession of Christian faith and in which unbelievers could possess Christian virtues.

There is some truth to this critique. Aquinas said that in order to direct the multitude toward the temporal common good, the prince must be a good man. In turn, Maritain argues that the same must be said of the political elements animating and forming a city today, then adds that such moral rectitude “presupposes in fact the gifts of grace and of charity, those ‘infused virtues’ which properly merit, because they come from Christ and are in union with Him, the name of Christian virtues, even when as a consequence of some obstacle for which he is not responsible the subject in whom they exist does not know or fails to recognize the Christian profession.” Even in The Peasant of the Garonne, Maritain argues that because all men are members of Christ potentially, we should presuppose that “the non-Christian we are speaking to doubtless has grace and charity—since we are in no position to judge the innermost heart—then we should equally presuppose that he is in good faith.”

On the one hand, the concept of unbelievers as Christians in potentia was hammered out in debates over how Christian Europeans should relate to the pagan residents of the New World they had just discovered. If the natives were potentially Christians, they needed to be treated well and to have their natural rights recognized. A Christian in potentia is someone who must be respected because he might acknowledge Christ in the future; an anonymous Christian is someone who is already a Christian, even if he does not acknowledge Christ.

On the other hand, Maritain’s conviction that grace is animating the unbeliever is not the presupposition of historical Christianity. More significantly, it points to the greatest limit of Maritain’s political thought: the degree to which it relies on things that come from thematic Christian faith but are not reducible to it. Much of Maritain’s effort builds on unconscious Christian moral structures, or the theological justifications underpinning a practical democratic creed. But Christian societies also have pagan moral structures and sentiments, and as Christianity weakens, these become more formative. As we can now see, implicit Christianity requires explicit Christianity in order to be maintained, perhaps more than Maritain acknowledged.

As we can now see, implicit Christianity requires explicit Christianity in order to be maintained, perhaps more than Maritain acknowledged.

Moreover, the past half century has seen the further breakdown of institutional Christianity on which Maritain’s political project relies. Widespread, entrenched financial and sexual abuse have compromised the moral authority of the Church. Western democracies no longer agree on some of the practical principles of the democratic creed, such as religious liberty. As Ross Douthat outlined in a recent lecture for the Morningside Institute (subsequently published in First Things), the “soft hegemony” that Maritain sees Christianity exercising in a pluralistic democracy relies on doctrinal confidence and missionary zeal, which were deeply shaken in the aftermath of Vatican II and further injured in subsequent scandals.

Christian Politics Today

That said, the limits of his thought do not vitiate the valuable insights Maritain offers for Christian politics in the twenty-first century. His distinctions help us understand that contemporary disagreements about liberalism and its possibly imminent demise are debates over the analogical or univocal application of theological principles, or different readings of the historical sky. He clarifies why the analogical application of theological principles correctly marries theological truth with the necessities of the present moment. He reminds us that politics is about how to order our life together, not just creating ideals or defeating our enemies. He teaches us that we can order a society toward the temporal truths of Christianity, but that the temporal power of the state is no substitute for the spiritual power of the faith.

Maritain understood that pluralistic societies require that we cooperate with others on matters of practical principles, even if we disagree about the justifications for them and think that the best justifications for those are found in Christianity. It turns out that this is inescapably the case. Some Catholics who criticize Maritain and his disciples for failing to work for an explicitly Christian society are now excited about collaborating with secular radicals in their battle against the liberal order. Like Maritain and his democratic creed, they are willing to table the justifications for their political project for the sake of the practical principles on which their coalition can agree.

Maritain also understood what would be needed for Christian renewal, both implicit and explicit. He knew that any future Christendom would not look like that of the past, that the power of the law cannot make up for a lack of faith. This new Christendom would therefore need two additional principles. The power of the Holy Spirit working through Christians living contemplative lives and sanctifying secular society would have to be the heart of Christian political action, not the Church using the state to smite her enemies. Just as Benedictine, Dominican, and Jesuit spirituality corresponded to different historical conditions, he wrote, any new Christendom would have to come from a sanctity turned toward the secular world. This would entail lay people living lives of contemplation and charity, their work in the world animated by a vibrant life of prayer.

In addition, Christians must recognize that their politics will require suffering and that they will not necessarily end in the triumphant victory of the kingdom of God being established on earth. Christians in the twenty-first century will look more like Gandhi than Charlemagne. Today, we hear calls for Catholics to seize the structures of the state and use them to direct society toward a Christian understanding of the common good. In Man and the State, Maritain argues that Gandhi’s courage in endurance was an appropriate form of spiritual warfare for Christians seeking to gain control of the state and use it for noble means. He then offers a caution: “Even if they cannot get to know and supervise its complicated legal and administrative controls, they can confront the whole machine with the bare human strength of patience in enduring suffering for the sake of claims that are inflexible and just.”

This resonates with Ratzinger’s later claim that the strength of Christian politics lies not in political coercion without popular support, but the intrinsic truth of the faith. Christian humanism and a new Christendom can only be realized by means of the cross, Maritain wrote, “not of the cross as exterior mark or symbol placed on the crown of Christian kings, or decorating honorable breasts, but the cross in the heart, the redemptive sufferings assumed into the very bosom of existence.”