With the inauguration of President Joe Biden, one of the most remarkable chapters in American political history is brought to a close, and another begins. The new president promised—and pleaded with his fellow Americans for—a new day of unity, in an inaugural address that almost completely neglected to say what the new administration intends to advance as a public policy agenda. (There were more policy implications in the benediction by Rev. Silvester Beaman than in the president’s address.) Evidently the president and his speechwriters believed that they needed to emphasize the unifying message above all, particularly after the antics of President Trump in his last two months in office.

It’s the duty of good citizens, I believe, to support President Biden wholeheartedly when they believe he is right, and to oppose him honorably when they believe he is wrong. As a conservative, I expect to do a lot more opposing than supporting. But the important thing to remember is that, in the shared enterprise of American constitutional government, our partisan counterparts are our opponents—but not our enemies. The January 6 mob attack on the US Capitol was committed by people—and egged on by a president—who had dissolved this distinction entirely.

But to those who think that our present moment represents the nadir of overwrought partisanship in our history, I say it is not so. Partisanship is strong drink, and moderate consumption of the intoxicant has always been difficult. Herewith some recommendations for reading on partisan moments in American history.

It is commonly said that the founders of the United States failed to anticipate the emergence of organized political parties. It is certainly true that the foremost founder, George Washington, warned his country about “the baneful effects of the Spirit of Party” in his farewell address in 1796. But one reason he did so is that he had seen that spirit grow very powerful in his innermost circle—his first cabinet—when Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton became the de facto leaders of the new republic’s first political parties while serving as Washington’s secretaries of state and treasury.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.These two men came to believe, as they squared off on questions of policy, principle, and constitutional interpretation, that the integrity of the nation’s new constitutional order, and the republican character of our politics, were at stake. The best account of the struggle between Jefferson and Hamilton at the level of ideas is Carson Holloway’s 2015 book Hamilton versus Jefferson in the Washington Administration: Completing the Founding or Betraying the Founding? For Jefferson, the principles and policies pursued by Hamilton marked out the road to monarchy, or at the very least the sacrifice of popular government to a self-perpetuating moneyed elite. For Hamilton, the machinations of Jefferson in ginning up opposition to his—and the president’s—policies threatened to dissolve the carefully wrought institutions of American republicanism in an anarchic acid bath of unconstrained democracy, or at the very least to jeopardize both the national union and effective government.

The idea that the victory of the other side spells doom sounds rather familiar, doesn’t it? In important respects, both men’s vision was clouded by their partisanship, making each of them prone to exaggerate how dangerous the other truly was. This was merely the first instance of a recurring pattern in American partisanship.

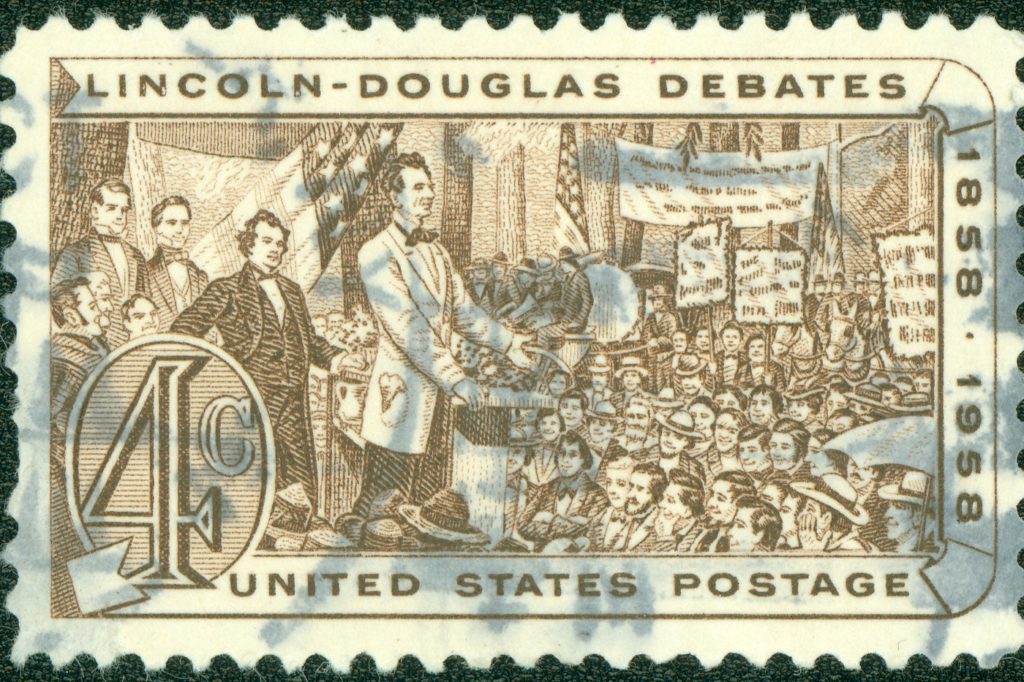

Abraham Lincoln, on the other hand, saw quite clearly that a dagger was aimed at the heart of America’s founding principles by the “popular sovereignty” policy on territorial slavery espoused by his great opponent, Stephen A. Douglas. To abandon the time-honored view that slavery was an evil to be placed “in the course of ultimate extinction,” and to treat it instead as a matter of moral indifference, was in Lincoln’s view a betrayal of the propositions on which the American constitutional order was based. Thus to attack the country’s principled foundations, like sappers, was to threaten the collapse of free government entirely. And so Lincoln revived his moribund political career to oppose Douglas with every argument and stratagem at his disposal.

The tale of Lincoln’s first (electorally unsuccessful) joust with Douglas is told most vividly by Allen Guelzo’s Lincoln and Douglas: The Debates That Defined America (2008). Lincoln’s fellow Republicans worried at times about his “house divided” rhetoric, and about his explosive insinuation that the Dred Scott decision was cooked up in 1857 by “Stephen, Franklin, Roger, and James”—a senator (Douglas), a chief justice (Roger Taney), and two presidents (outgoing Franklin Pierce and incoming James Buchanan). Even honest Abe could be tempted to say more than he could prove, which is a salutary lesson for us all. But taken all in all, his was a partisanship of the highest order, a partisanship that transcended partisanship by calling all Americans back to first principles.

A final recommendation concerns an episode in twentieth century history now forgotten by most people.

A final recommendation concerns an episode in twentieth century history now forgotten by most people. As Allen Weinstein begins his 1978 book Perjury: The Hiss–Chambers Case, “Once upon a time, when the Cold War was young, a senior editor of Time accused the president of the Carnegie Endowment of having been a Soviet agent.” The editor was Whittaker Chambers, a repentant former Communist, and the president of the Carnegie Endowment was Alger Hiss, who had until quite recently been a high-ranking official in the State Department, in which capacity he had attended the Yalta Conference, and had been a major player in the creation of the United Nations. But Hiss, it was proved, had indeed been a traitor to his country in the service of the Soviet Union.

A handy cudgel for Republicans to bash Democrats was the charge that they were “soft on Communism,” and worse yet, infiltrated by Reds. No surprise, then, that Chambers’s accusation against Hiss was championed by a young congressman on the House Un-American Activities Committee named Richard Nixon, who was a man on the make. The case had all the earmarks of passionate partisanship: shrill accusations of treason, and equally shrill denials; a president (Harry Truman) trying to minimize the fallout and keep his distance; high-temperature hearings on Capitol Hill; a perjury trial in federal court. And for decades afterward, far-left partisans at magazines like The Nation vehemently denied Hiss’s guilt, calling his downfall the first episode in the terrible era of “McCarthyism” (though the case was over before Joseph McCarthy got started). Meanwhile Whittaker Chambers helped William F. Buckley, Jr. start National Review.

But Weinstein, a young liberal historian who began his research believing that Hiss was innocent, came to the honest conclusion, after voluminous exploration of primary source material, that he was guilty. His book is first-rate investigative history, minute in its details and compelling in its narrative. And it is a cautionary tale, a reminder that once in a while a true enemy can be found in our midst, and that it is incumbent on partisan opponents to work together to find the truth, rather than retreating to their corners to shout imprecations at each other.