Americans are a fundamentally conscientious people—and Americans took proactive measures to beat COVID long before government measures were in place. Last week I argued here at Public Discourse that lockdowns don’t work, and this week I argue that, contrary to popular narratives, Americans have been fairly diligent about social distancing, even in places and times where they were under no government order to do so. Furthermore, there’s virtually no evidence that government orders actually have the effect of increasing social distancing. As a result, policymakers should focus their efforts on high-information-content signals to the public, rather than strict lockdowns.

Americans Are Good at Social Distancing

Americans are actually pretty good social distancers. The best way to measure social distancing is with the “community mobility reports” that Google provides. These reports estimate how much the visitation of key places—like workplaces, transit stations, restaurants, stores, parks, and residences—has changed versus a baseline period. They use cell-phone-location data, and therefore don’t rely on people to be honest about their activities. Crucially, they’re available on a daily basis, in a large number of countries and regions around the world.

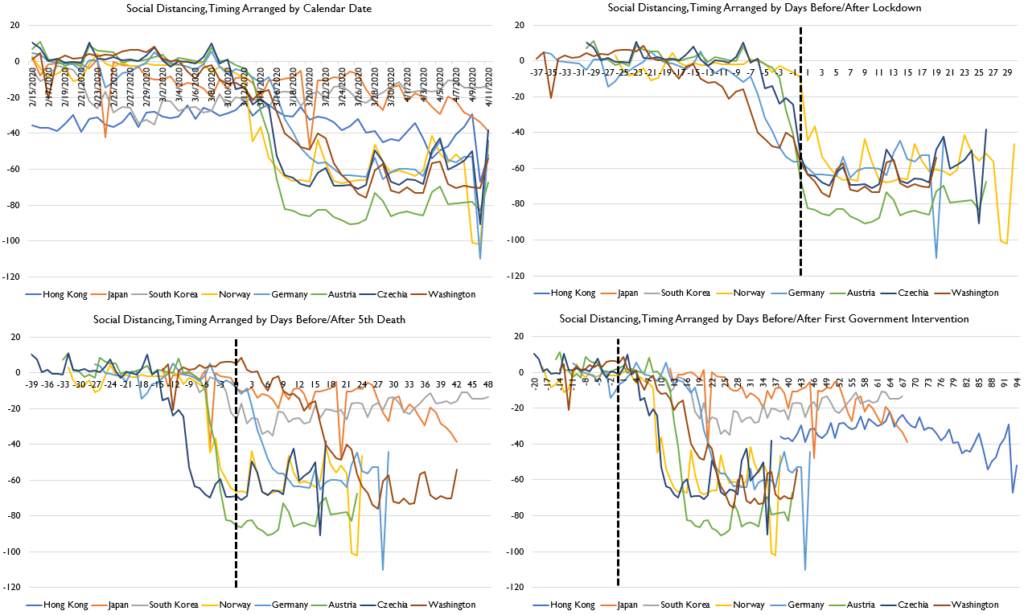

We can start by looking at how social distancing has proceeded in countries where local outbreaks appear to have been pretty well managed. As just a sample, I compare Norway, Germany, Hong Kong, Korea, Japan, Austria, Czechia, and Washington State. Below, I provide four related graphs. All four graph the same data: an index of social distancing developed from Google’s community mobility reports. Lower values indicate more social distancing as measured by amount of activity at workplaces, stores, restaurants, and transit stations. Moreover, as Google-measured devices spend more time at residences, I subtract that value: thus, a lower value for my index indicates more time spent at home, and less at work, restaurants, stores, etc. The four graphs align the timing of this data in four different ways: first simply by date, then reorganized so that “day zero” is the day a region went into lockdown (Japan, Korea, and Hong Kong never went into lockdown, and so are missing), or reorganized by the date a region had its fifth confirmed death from COVID-19 (Hong Kong has only had four deaths despite over 1,000 confirmed cases), or reorganized by the date of the first public government intervention to respond to COVID (the earliest interventions in Hong Kong, Japan, and South Korea all came before the first day of Google’s data).

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.The key takeaway from this graph is that actual, real-world social distancing in places with effective responses to COVID-19 is not very well predicted by calendar date, and is also not very well predicted by the date of the fifth COVID death. At first, lockdowns appear to predict social distancing well. But in virtually every region, massive social distancing comes a few days or weeks before lockdowns. Politicians appear to implement lockdowns as a response to social-distancing behaviors in their areas, rather than as drivers of those behaviors.

The only measure that reliably precedes social distancing, and which places the Asian data in a rationally comprehensible relationship to the European data, is to assume that the most important government intervention is simply the first government intervention—that the key thing is not “date of lockdown” but “date the government acknowledged a real problem and made some response.” By this measure, all of the European countries and Washington State are practicing more social distancing than the Asian regions. I didn’t show it, but there is no evidence that Taiwan is practicing any social distancing at all, because their strategy has rested entirely on travel restrictions, and thus there’s been no meaningful local community transmission in Taiwan.

Strikingly, Washington State is practicing more extensive social distancing than any of these European regions other than Austria (which will be coming out of lockdown soon). Thus, it doesn’t seem like lockdowns are the factor that initiates social distancing in places with effective responses. “First government notice” seems like a more plausible first mover in this sample of places.

Lockdowns and Government Notice in the U.S.

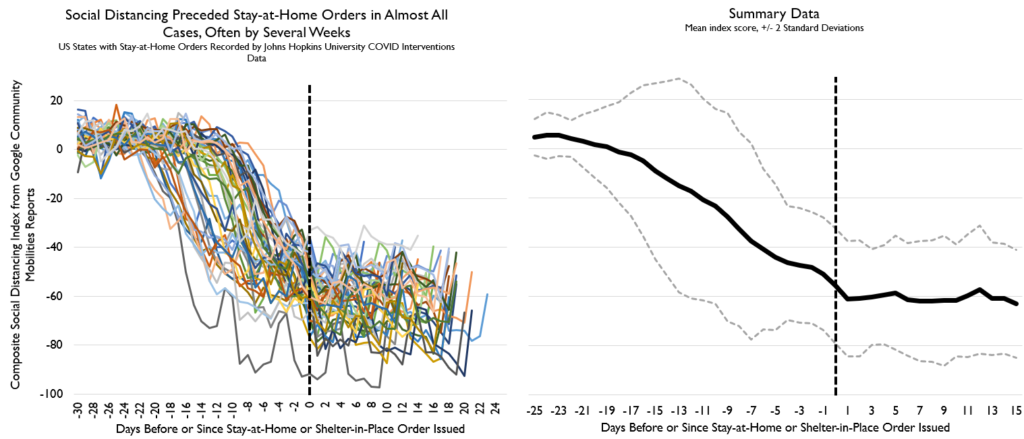

This can be demonstrated in U.S. data for all states as well. The figures below present measures of social distancing arranged by when U.S. states imposed stay-at-home orders.

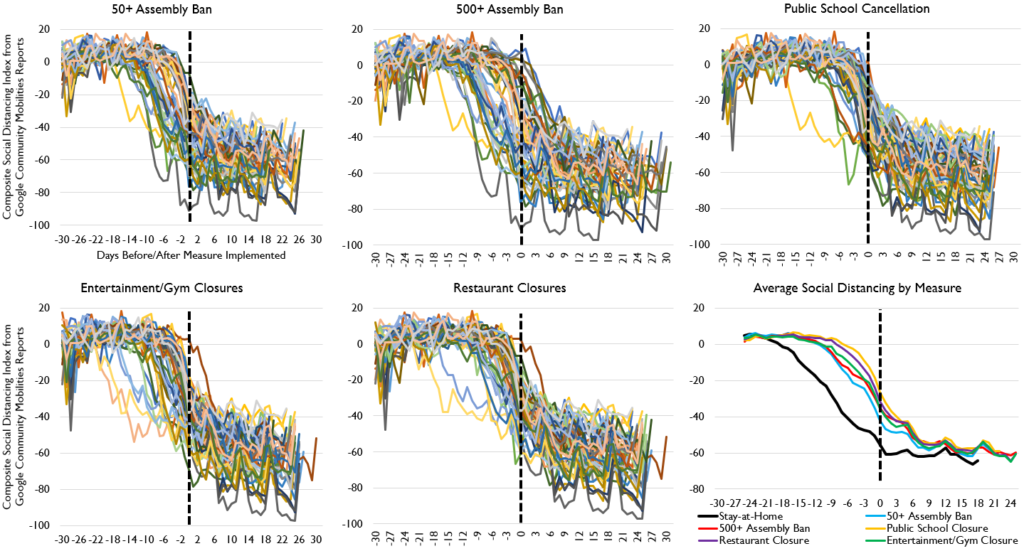

In virtually every U.S. state, large-scale social distancing came before stay-at-home orders. There’s simply no evidence that Americans resisted social distancing until ordered to comply. Instead, the evidence suggests that Americans were voluntarily social distancing up until the date when they received shelter in place orders. Nor is this effect driven by other policies. The figures below show the same data, arranged by the date on which assemblies of over fifty were banned, the date on which assemblies of over 500 were banned, the date on which public school was canceled, the date on which restaurants were closed, and the date on which entertainment facilities were closed. Across all of these policies, social distancing very clearly began before the policy was implemented.

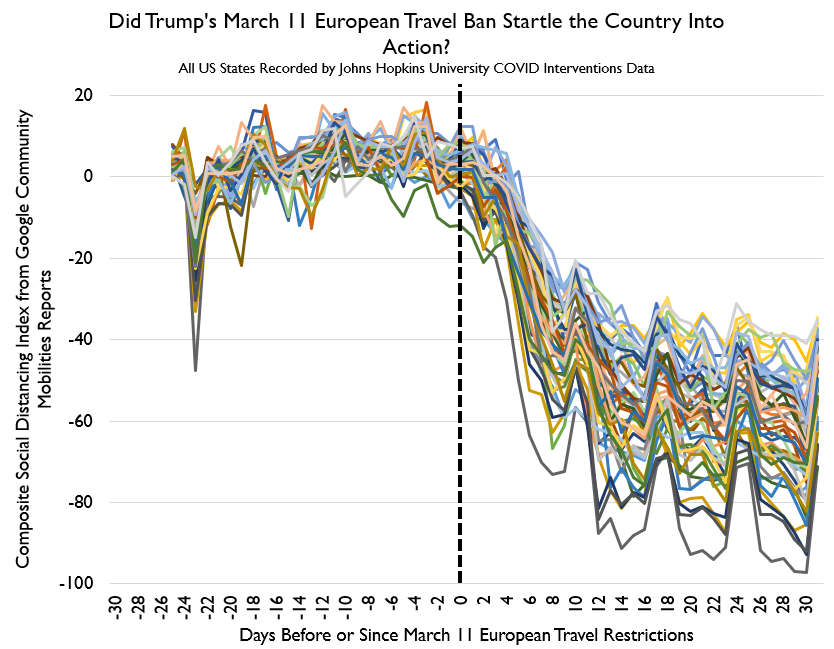

None of the state-level policies identified appears to be responsible for social distancing. However, it turns out that there’s no need to get so complicated. Almost every state’s social distancing turns out to have begun at almost the exact same time: March 8–13, with March 11 being the major inflection point. Put bluntly, March 11 is the date on which America began socially distancing. Before March 11, essentially only Washington State—and to a much smaller extent California—were socially distancing. This is no surprise, since Governor Inslee declared a state of emergency in Washington on February 29, and California counties had begun declaring local health emergencies as early as February 10. Where emergencies were declared early, social distancing began earlier as well.

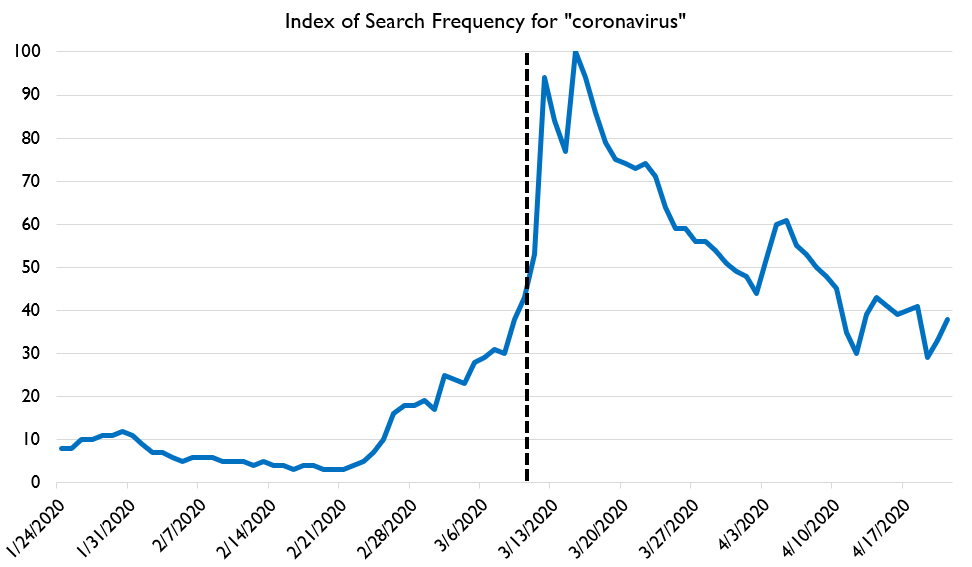

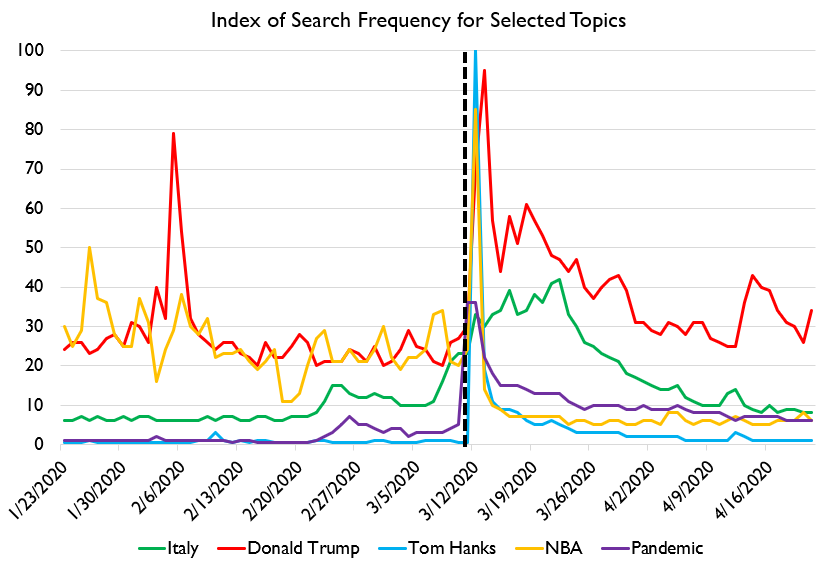

But what happened on March 11? March Madness was cancelled, and the NBA season was suspended. Several celebrities announced that they were infected with COVID. March 11 was also the date when the World Health Organization declared COVID a pandemic. A bit earlier, on March 9, Italy went into a widely publicized severe lockdown, which shocked many people around the world. Coronavirus was dominating headlines around March 11, and also dominating Americans’ Google searches. Here’s a graph of indexed search volume by day for “coronavirus” showing the peak just after March 11:

And here’s a graph of some major COVID-related news items around the same time:

Plausibly, the NBA, Tom Hanks getting COVID, or Italy’s lockdown could all have driven Americans to begin social distancing. More likely, it was some combination of all of them. But President Trump also made news in that time window by putting travel restrictions on flights from Europe on March 11. Debates about whether this was a good policy or not made news on almost every major network, and Trump’s choice to tighten control measures despite fairly consistently downplaying the severity of the virus before that date almost certainly set off alarm bells even among Americans who were skeptical of COVID control measures.

It’s hard to say exactly what caused the massive spike in social distancing after March 11. Media narratives, cultural institutions, and political leaders probably all had a role to play. But, as the graph below shows, there can be no debate that March 11 or March 12 is when social distancing began in America.

And while we can’t know for sure if the post–March 11 social-distancing measures were caused by Trump’s change of tune on COVID, there’s good reason to think policy leadership really does matter. The fact that social distancing began earlier in Washington and California, corresponding to earlier policy responses, and the fact that internationally effective social distancing seems related to the date of first policy response, suggests that it is at least plausible that it was the March 11 travel restrictions (and public debate about them) that triggered social distancing. Why Trump’s earlier restrictions on travel from China did not cause a similar response is debatable, but it seems at least possible that only restricting travel from China might have communicated to Americans that the outbreak remained basically local in China—and was therefore nothing to worry about—while restricting travel from Europe revealed that the pandemic could and would reach rich, developed, democratic, Western countries.

If this theory, that social responses are triggered by policymakers’ communicating the presence of an emergency, is correct, then Trump’s choice not to declare a national emergency until March 13 was a devastating mistake, as it almost certainly led to thousands of preventable deaths. If information is what matters, then President Trump’s personal leadership is even more decisive for public-health outcomes, and therefore excess deaths are more directly attributable to him personally.

President Trump was not alone in tarrying to declare such an emergency: March 11 was also the day the World Health Organization declared a pandemic. I have written elsewhere about the ongoing moral train wreck that is the WHO. But, again, if the theory that early emergency warnings trigger social responses is correct, then the WHO made the pandemic far worse than it needed to be by delaying their warnings about how severe it would become.

The Extent of Social Distancing

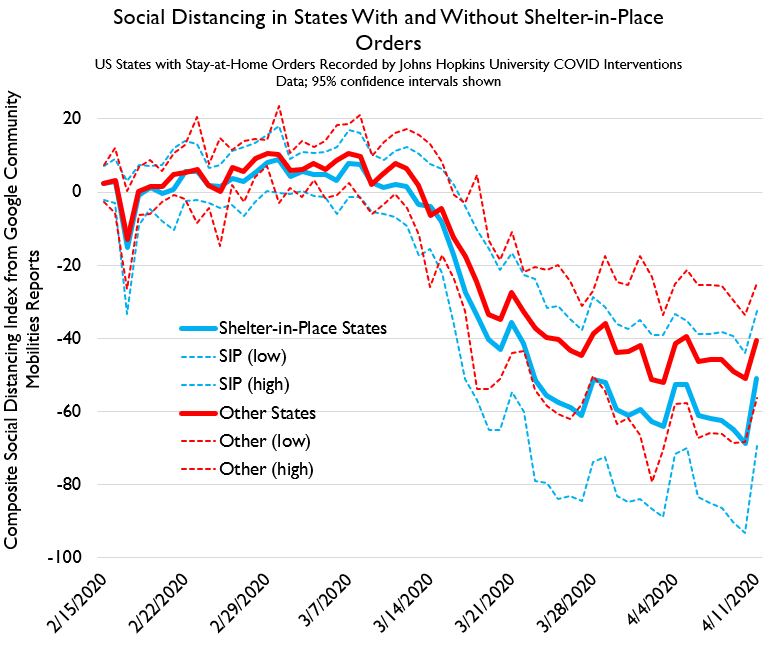

Up to this point, I have focused on the timing of social distancing, not the extent. Careful readers doubtless noted that Hong Kong, Japan, and Korea all had far less social distancing than European countries with lockdowns. Is it possible that while lockdowns do not influence the timing of social distancing, they do influence its scale? There is actually some evidence of this. While issuing a lockdown probably doesn’t initiate social distancing, it might make social distancing a bit more aggressive. The figure below shows how social distancing has proceeded since March 11 in states with and without shelter-in-place orders (SIPs). States without such orders do appear to have slightly less extensive social distancing.

But the variability within states with SIPs is enormous: some SIP states have social distancing as extensive as the most severely locked-down European countries (like Washington), whereas other SIP states have less social distancing than any of the non-SIP states. One possibility is that the propensity to enact SIPs is itself affected by the same social, political, and cultural factors that affect compliance with and enforcement of an order. In other words, if imposing a lockdown is politically difficult, it may also have no effect, since people will tend to resist it and enforcement bodies will not aggressively pursue violators. Thus, despite having one of the stricter lockdowns in the country, Kentucky actually has less than average social distancing.

I’m not alone in noting that states with stricter policies don’t seem to have stricter social distancing: a brand-new working paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research finds that, even with a battery of controls, shelter-in-place orders have no significant effect on almost any metric of social distancing, while state-declared emergencies increase daily time spent at home by almost three hours for the average person, a huge effect. Information motivates social distancing, not compulsion.

But it is enough to note that social distancing efforts in states without shelter-in-place orders have been more aggressive than what has been observed in Japan, Korea, Taiwan, or Hong Kong, and are only marginally less extensive than what we see in states with such orders. In fact, the difference is not even close to statistically significant. While stay-at-home orders might slightly increase the amount of social distancing people undertake, this effect is extremely modest compared to the overwhelming effect of early and compelling information inducing voluntary social distancing.

Furthermore, it’s not clear that the extent of social distancing is very important. Early intervention against an epidemic can have a huge effect. But more intense intervention coming later is not nearly as effective: that’s just the nature of exponential growth. Doing twice as much social distancing two weeks later is probably less useful than half as much two weeks earlier. Thus, the most important question for policymakers is not, “How can we make the eventual peak amount of social distancing as extensive as possible?” but “How can we get people to adopt social distancing measures as swiftly as possible?” Shelter-in-place orders are probably not very effective tools for achieving the highest-impact social distancing response.

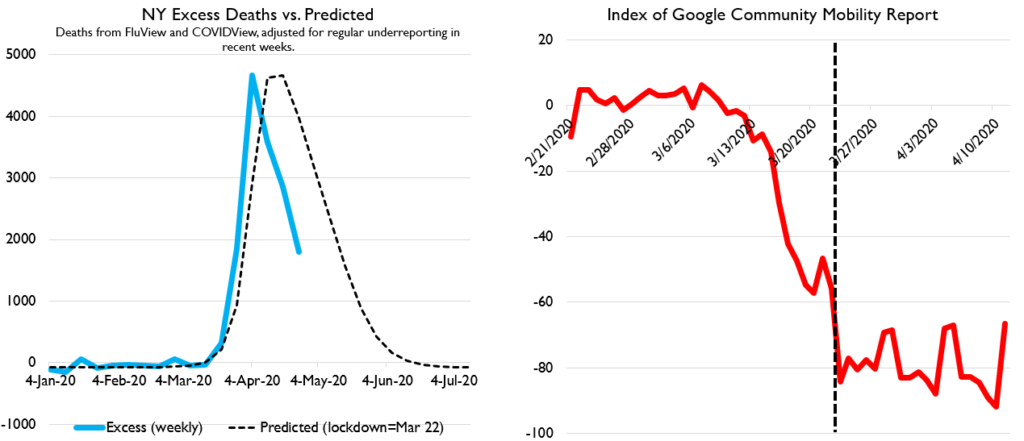

This can be seen very clearly in New York. We don’t have daily death data for New York, but we do have reliable weekly data. Furthermore, we can guess what deaths should have been if the disease was spreading exponentially before the lockdown, then the lockdown sharply reduced deaths. This is similar to the approach I took in my Public Discourse essay last week on lockdowns. However, in response to criticism, I have used a more precise method, proposed by a researcher who supports lockdowns, to identify the date when lockdowns should have reduced deaths. This method can be applied to New York, and we can also look at when New York began to show signs of social distancing.

New York’s peak in deaths arrived fully a week earlier than even the most optimistic models of the effect of lockdowns would have predicted, and its decline after that peak has been faster than expected. But this is no surprise at all: social distancing in New York, like everywhere, began in earnest about ten days before the shelter-in-place order went into effect. It’s not the lockdown saving lives: it’s New Yorkers’ voluntarily restricting their own lives to protect those around them.

Information and Misinformation from the Media

Some early academic study has already identified the potency of information by exploiting, of all things, different attitudes toward COVID among Fox News hosts. Sean Hannity and Tucker Carlson took very different lines on COVID early on: Carlson argued that it was a major threat, while Hannity pooh-poohed it. This has enabled academic researchers to explore the specific effects of information, especially since Carlson and Hannity viewers tend to be demographically similar. By exploiting differences in when their shows aired compared to sunset times (which influence indoor activities like TV viewership), and also directly surveying viewers of each show, the researchers found that counties where more people watched Hannity rather than Carlson have experienced much higher rates of death from COVID. At the individual level, their survey found that Carlson viewers took personal behavioral choices to protect themselves about three to thirteen days earlier, which was consistent with reduced infection and reduced death. Getting more accurate information earlier from Carlson saved lives, while Hannity’s month-long delay in recognizing the severity of the situation led to his viewers’ delaying their responses and dying at higher rates.

In other words, it’s not just political leaders: media personalities could have saved lives too. Had more journalists and talk show hosts all taken COVID as seriously as Tucker Carlson did in February, many lives could have been saved. In this case, Sean Hannity is the counter-example, but it’s trivially easy to find articles in January and February from every major news outlet telling people not to wear masks, that racial stigma against Chinese people was as large a threat as the disease itself, or that major social distancing efforts were overreactions. This supports the idea that events like Tom Hanks’s going public about his diagnosis and sports leagues’ cancelling their seasons probably had a large impact on social distancing as well.

The Truth about American Social Distancing

Americans began to practice social distancing not because they were ordered to do so, but because, belatedly, our political and cultural leaders woke up to the risks of COVID and sounded the alarm around March 8–13. Having received credible information about the risks of COVID, Americans responded with remarkable solidarity, adopting stringent social distancing measures even in states without stay-at-home orders. These social distancing measures have almost certainly saved tens of thousands, perhaps even hundreds of thousands, of lives. But policymakers (outside of Washington State and some county officials in California) cannot take credit for this achievement: it was a grassroots campaign by Americans of all stripes working together to protect each other.

There’s more to it than that. Whenever people tell you that Americans need lockdowns because before lockdowns they were refusing to socially distance, they’re not just smearing Americans, they’re also wrong on the facts. Americans, like people in almost every country, were quicker to understand the risks than most of the people who govern us. Alas, had our leaders taken the threat seriously a month earlier, and communicated the risks to Americans more explicitly, COVID could have been a flash in the pan. Instead, many thousands of Americans are going to die unnecessary deaths.

In the meantime, the elites who construct social narratives are trying to tell a story where COVID is being beaten by smart policymakers—tough policymakers—making hard calls informed by careful scientists. It’s an elite-focused narrative in which whether we beat COVID or not depends on what rules we write. This is the narrative China has promoted, and it’s the narrative the WHO has promoted, not least because it lets them off the hook: their delay in providing information isn’t a big problem if outcomes are driven by the policies set by a few elites.

Americans should reject this narrative. China’s suppression of information, the WHO’s dilly-dallying with declaring a pandemic, and President Trump’s refusal to take COVID seriously enough from an early date, all cost lives—not because they changed policies, but because they contributed to a false sense of security in the public. People who told the fearsome truth early (like Tucker Carlson) saved lives. Americans who adopted voluntary social distancing early saved lives. You saved lives. Not your governor or some other johnny-come-lately leader who finally noticed there was a pandemic three months after it had begun. You.

The reason lockdowns don’t work is not that social distancing doesn’t work. Cancelling school, limiting assemblies, reducing interpersonal contact—all of these, up to a point, help reduce the spread of a disease. The reason lockdowns don’t work is that once you’ve limited large assemblies, cancelled school, and taken a few other high-profile measures, the mortality risk of an epidemic is already so thoroughly communicated to society that most people will have already voluntarily adopted a de facto shelter in place policy. Adding a formal rule achieves very little, unless you send police door to door to arrest violators, which nobody is keen on doing, and which would be a gross violation of basic liberties without reducing the spread of the disease. Meanwhile, policymakers need to focus on preparing for the long, grueling campaign against the disease after unsustainably intense social distancing ends, as it naturally must, whether voluntary or mandated. Policymakers need to focus on setting up quarantine sites, expanding testing, securing supplies of masks, and developing practical how-to guides for businesses to conduct their affairs safely.

This is important to keep in mind as many Americans want to “reopen.” If information and public perception of risk are the key, reopening will get very tricky. Removing a shelter-in-place order might be fine, but we can’t actually allow ourselves the illusion that our lives can to return to normal. We’re going to be wearing masks throughout the hot, humid summer. Kids are probably not going back to school until August at the earliest. Summer ball is cancelled. We won’t be attending concerts before July or August. Even if the law doesn’t compel these choices, Americans will need to voluntarily make them, or else we will get a massive second wave of death. What matters is not the policies we pass, but the lifestyles we adopt.

If Americans can maintain a war-footing against COVID and sustain the kind of mass mobilization to defeat a mortal foe that could easily kill more Americans than the Viet Cong or Hitler or the Kaiser ever did, then we can beat COVID. But this requires personal choices to protect our neighbors by practicing social distancing. It won’t be achieved by the state making more regulations, but by diligent, conscientious citizens shouldering their personal responsibility to annihilate COVID through social distancing. If we fail in this, if we do not heed the information we are receiving that clearly shows the likelihood of huge death tolls, then there will be terrible consequences.