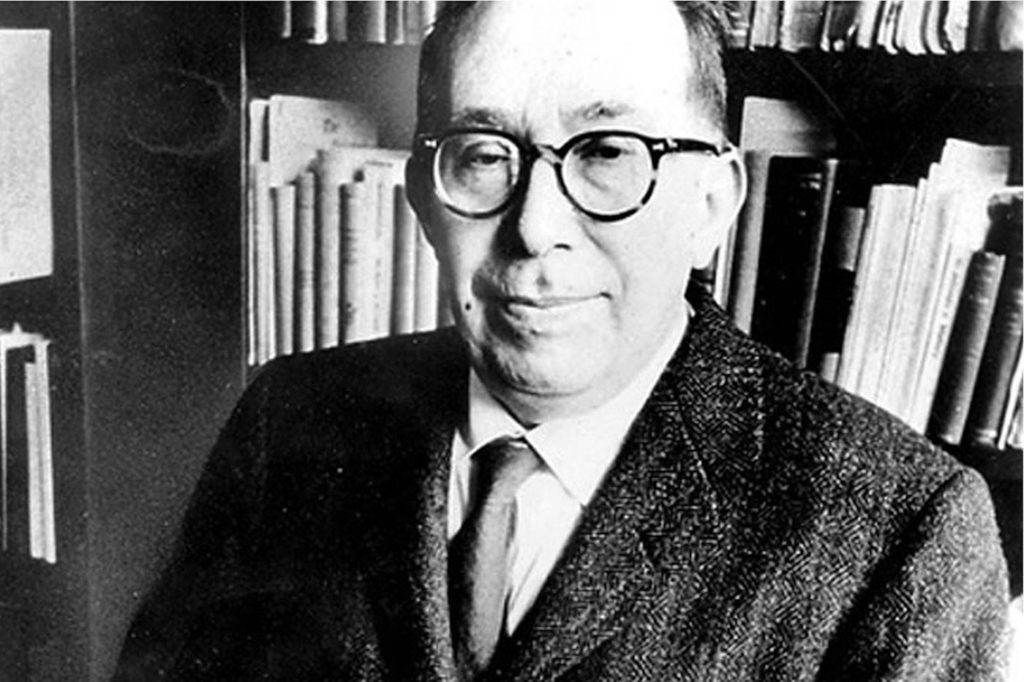

A book titled Leo Strauss and his Catholic Readers might initially seem strange. Is there common ground between an apparently non-believing Jewish political philosopher and a handful of believing Roman Catholic political philosophers? This volume demonstrates that the faithful Catholic does share a range of common goals and interests with Strauss. To name just a few, there is a shared belief in natural standards of the just and the good, a deep interest in the relationship between faith and reason, and a faith in reason’s ability to transcend its own historical context and arrive at enduring truths.

While Strauss himself is dead, his words and influence live on in his works, his students, and his thoughtful readers. One is reminded of what Adams said to Jefferson when they famously renewed their correspondence in retirement. It is the belief of this impressive crop of scholars that Roman Catholics and Leo Strauss ought to explain themselves to one another. The result is a treasure trove of reflections on a range of themes in Strauss’s thought, accompanied by explanation of the areas of agreement, and a careful, charitable explanation of Catholics’ reasons for disagreement.

The book is a collection of essays, bringing together the work of an impressive array of scholars. It is divided into three parts. Part one revolves around themes connected to Strauss’s recovery of natural right and his qualified appreciation―but ultimate rejection―of Thomistic natural law. It includes Robert P. Kraynak’s wide-ranging essay on reason and faith in Strauss, V. Bradley Lewis’s account of Charles N.R. McCoy’s engagement with Strauss, Geoffrey Vaughan’s defense of Strauss’s worries about the rigid and idealistic features of natural law, Marc Guerra’s comparative study of Strauss and Benedict XVI, and Douglas Kries’s study of Fr. Ernest Fortin’s encounter with Leo Strauss.

Part two brings together essays exploring common concerns of Catholics and Strauss. Gladden Pappin explores how A.P. d’Entrèves, Charles McCoy, and Yves Simon thought about the relationship of philosophy to society in comparison and contrast with Strauss. John Hittinger analyzes a lecture Strauss gave at the Jesuit University of Detroit and finds useful lessons for Catholics. Carson Holloway rereads Strauss’s lecture “Progress or Return” and defends a Catholic approach to the theologico-political problem. Gary Glenn contends Catholic natural law has a flexibility akin to natural right. J. Brian Benestad’s essay wraps up this section with a Straussian critique of historicist Catholic theology.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.Part three is titled “Leo Strauss on Christianity, Politics, and Philosophy.” Giulio de Ligio reflects on the relation in Strauss’s thought between politics and philosophical investigation. In one of the most interesting chapters, James R. Stoner argues that Strauss accepted classical teleological metaphysics as a true account of nature. Philippe Bénéton brings Strauss into dialogue with Pascal. Finally, Ralph C. Hancock (the only non-Catholic contributor) explores Strauss’s critique of Christianity.

There is a substantial overlap in the themes explored across the sections of the book. Sometimes a chapter can feel quite different from the others with which it is grouped, and one could make a case for ordering the chapters differently. There also are arguably some gaps in what the book covers. For example, readers might want to see more engagement with the work of Fr. James Schall, who is correctly said to be “preeminent” among the Catholic readers of Strauss.

Still, both believing and non-believing students of Strauss will find this book rewarding. Most will agree with Hittinger that “the challenge to read political philosophers in a fresh, non-derivative way” is perhaps Strauss’s greatest legacy. In its own fresh, non-derivative reading of Strauss and his interlocutors, this book contributes to repaying the debt Catholic political philosophers owe to Strauss for the revival of political philosophy.