Many children’s books about interfaith relations are nice, but their messages often don’t go much deeper than “let’s be kind to each other.” Even the brilliant secular book on living with diversity, Do Unto Otters by Laurie Keller, accomplishes only this. But we can’t teach about interfaith relations if we strip the characters of faith itself.

At last we now have the insightful children’s book A Muslim Family’s Chair for the Pope: A True Story from Bosnia and Herzegovina written and delightfully illustrated by Stefan Salinas, a Catholic artist from the San Francisco area.

A Muslim Family’s Chair for the Pope follows the true story of Salim, a Muslim woodworker in Bosnia. When Salim hears about plans of Pope Francis to visit Bosnia in 2015, he comes up with the idea to carve a chair for the Pope to use when he celebrates Mass during his visit. Salim tells us, “Immediately, in my head appeared an image of a chair for the Pope, and I was its creator!”

A Muslim Family’s Chair for the Pope provides a way to introduce children to interfaith relations, in particular to Catholic-Muslim relations, with a robust celebration of faith and religious practice, as witnessed through the lives of the Muslim and Catholic characters in the book. There is no vague, lowest-common-denominator kumbaya in this book. Instead there are people praying, there are sacred images, and there is even theology: we learn who Jesus is for Catholics (“Son of God”) and for Muslims (“a prophet”). It celebrates imams, priests, and nuns. And, not least of all, the book honors the Pope, thanks to a Muslim artisan’s desire to do something beautiful and kind for his Catholic neighbors.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.The artwork of Salinas shows great respect for family life as well as for religiously diverse communities sharing the public square. It acknowledges there can be strife between religious communities, but it doesn’t stop at the point of darkness.

Salinas takes us, instead, on a tour of the adventure of Salim’s chair for the Pope. Salim approaches a local Catholic priest with his idea, which then winds its way up the ladder of church leadership, eventually being approved by Rome. We learn about Salim’s interior questioning, wondering why he, a Muslim, is doing this for a Roman Catholic Pope. Salim talks with God about this; he prays to make sure he is doing the right thing. We learn about Salim’s collaboration with local Catholics in the design process, and about how Salim and his sons volunteer their time and talent for this project.

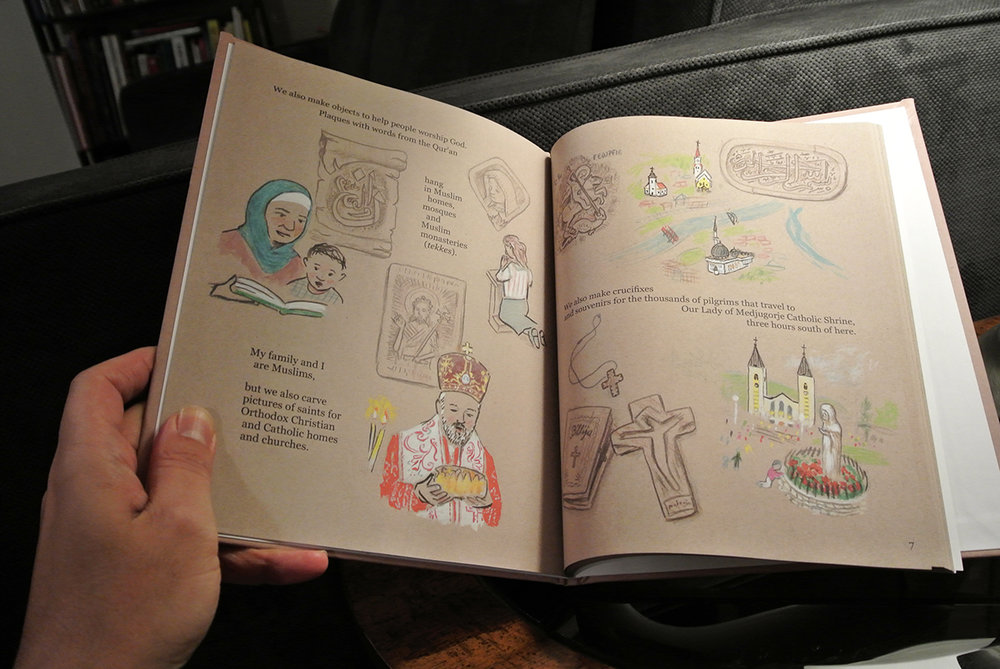

The illustrations of Muslims at prayer in a mosque and Catholics at Mass in a church offer a way to talk with children about the people of each religious community and the ways in which they worship God. Also helpful, and delightful, are the illustrations of religious art. We learn in some detail about the individual Christian images Salim carves into the chair, and the meaning of the Christian stories behind these images. We read a bit of the Quran and a bit of the Bible, learning about the Islamic art of Arabic calligraphy of Quranic texts and seeing some Orthodox icons too. The drawings of cities feature a mix of church spires and minarets intertwining side by side. And we see Pope Francis meeting with local Muslim, Christian, and Jewish leaders. Perhaps most importantly, the Muslim and Catholic characters in the book live out their faith lives joyfully.

A Muslim Family’s Chair for the Pope is just an introduction to the realm of Catholic-Muslim relations through the story of one character and his neighbors. It does not try to—nor does it need to—tackle every aspect of this vast, complex topic. This is important, because if we view Catholic-Muslim relations solely as a topic of global, multi-century issues, we risk fostering a state of ‘interfaith paralysis,” fearful, with no idea where to begin.

Moreover, at a time when religion in public life is often framed through a narrow political lens, Christians and Muslims have an opportunity today to be among those who are helping society to view religion through other lenses too, such as the lens of how we relate to people in our day-to-day lives. This is not to say that we ignore real world violence and suffering; not at all. Rather, alongside recognition of the bigger issues, bringing our attention to our own day-to-day lives can help us see not only ways to love our neighbors but also to find ways to carry out the delicate and important task of preparing children to live in our multi-faith world as well as the diverse mini-universe of any given city block. Salinas’s book helps to provide such a point of entry for discussing interfaith relations with children.

Salinas’s book reminds me of the wisdom of St. John Paul II, which he shared thirty-two years ago in his address to Muslim youth in Morocco:

Christians and Muslims, in general we have badly understood each other, and sometimes, in the past, we have opposed and even exhausted each other in polemics and in wars. I believe that, today, God invites us to change our old practices. We must respect each other, and also we must stimulate each other in good works on the path of God.

This story of Salim’s good work helps us share with children an alternative to exhausting “each other in polemics and wars.” This story shows in concrete terms what such “good works on the path of God” can look like, and it provides a way to introduce children to doing such “good works on the path of God” for others, including people of other faiths. A Muslim Family’s Chair for the Pope is rooted in the centrality and wonder of God in the lives of the Muslim and Catholic characters in the book, and it translates this wonder into Salim and his collaborators, Muslim and Catholic alike, responding to God through good works carried out both for and together with each other.

This book is suitable for introducing Catholic children to Islam and Muslims, and for introducing Muslim children to Catholicism and Catholics. This is a very Catholic book; while it is certainly one I recommend for adventurous Protestants and atheists alike, it is not one likely to be embraced with enthusiasm by Bible-only Christians or those who are allergic to religion. This would be a wonderful gift for children, nieces, nephews, godchildren, and for the libraries of Catholic and Muslim schools, as well as public schools.

Salinas’s book is a celebration of the words of Jesus: “Love thy neighbor.” Woodworker Salim’s generosity is a celebration of loving one’s neighbors even when one does not agree with their religion. Yes, this is possible. And—as we learn from Salim—it can be beautiful too.