My father briefly attended a one-room schoolhouse on the Canadian prairies, the same one his own father had attended as a child. It was closed in the early 1950s, and children were bussed some miles to the nearest K-12 school. But while the school closed, the building remained open, serving as a community center for card games, parties, and dances. He tells stories of those parties, sometimes going by sleigh in the winter, with local musicians, story-tellers, and poets providing flavor and entertainment.

The building was a neglected wreck by my childhood, and, if I remember correctly, it was burned down by the local volunteer fire department for a drill. I do have a watercolor of it, however, with a frame made of wood from the building, gifted by a friend as a wedding present. It was a simple building, but a place of some importance for the neighbors.

Many of these same neighbors ran cattle, as did we. When it came time to process the calves—inoculations, ear tags, branding—neighbors would often pitch in and help each other. One weekend, we all went to the Andersons followed the next weekend at the Gibsons. There was a very set, albeit unspoken, set of roles at those events. The youngest children were kept away, as there is always some danger involved in sorting and moving cattle. Young men, as we thought of ourselves at eleven, “pushed” the calves up the pens and into the chutes, while the older men followed a clear set of demarcated roles, although it was clear that the twenty-somethings were given less responsibility than the forty-year-olds, with everything directed by those in their fifties and sixties.

It’s not nice work.

Afterwards, dinner was served, everything homemade. Mishaps of the day would be recalled, with great mirth at the offender’s expense. Which would, of course, lead to stories of past years, past mistakes, and legendary exploits of those long under the earth. In part, from hearing these stories I learned about my family, about my grandfather, who died long before I was born, about manners, roles, virtues and vice. You learned what was expected of you, what was deemed admirable, and what to avoid—what was considered a noble, good life.

Start your day with Public Discourse

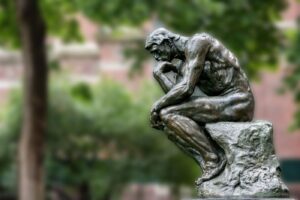

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.As Aristotle noted, humans are unable to thrive outside of the polis. Gods and beasts are self-sufficient, but humans are political animals, social beings, and they require institutions to educate and form them, to lead them to the full measure of humanity. Without family, school, law, religion, the market, and so on, we are incapable of full action. Those who believe that freedom is to be unencumbered by institutions are profoundly wrong. Institutions—reasonable, good, just institutions—are a condition of freedom and flourishing.

In our own moment, many note that our basic institutions—marriage, for instance—appear fragile or in decline. It’s no surprise to find that, as institutions decline, we do not find greater capacity for self-governance but rather more dependence, dehumanization, loneliness, and loss or confusion about identity.

Just over a year ago, Daniel Burns wrote a two-part review for Public Discourse on Yuval Levin’s book, A Time to Build, noting that we are “living through a social crisis” of “fragmentation and individualization of American common life.” We cannot circumvent our need for institutions, but our institutions can “no longer be taken for granted.”

Without family, school, law, religion, the market, and so on, we are incapable of full action. Those who believe that freedom is to be unencumbered by institutions are profoundly wrong. Institutions—reasonable, good, just institutions—are a condition of freedom and flourishing.

Explorations On a Theme

In 2021, Public Discourse intends to examine our need for institutions and possible ways to renew and rethink them. While readers can expect to see this theme recur throughout the year, we have in the last month, and particularly in the last week, launched this theme in a series of excellent essays. They’re worth the time to read and carefully consider.

In “Learning, Justice, and Gift,” Elizabeth Corey astutely reminds us that life is not simply about earning a wage and winning political battles. If we are to do justice to our humanity in its fulness, we should avoid the temptation to “catastrophize” our moment and give in to a vision of life as total politics. Humans need more than politics, however important those institutions are, and our schools and colleges should still attempt to offer an education in freedom, or a liberal education.

Education matters. We will not flourish as a people, let alone as a free people, if our educational institutions fail us. In our February long read, Daniel Burns returns to the thought of Levin, insisting in “A Time to Build Schools” that “The single type of institution best suited to resist” the forces that distort and weaken our character-forming institutions “is the mission-driven, tech-skeptical K–12 school.” In addition, Burns argues, if they are to be effective in forming people well, all contemporary institutions must grapple with “the catastrophically bad incentive structures” of social media, which “foster habits that make all of us into worse human beings.”

Sometimes we must build new institutions to meet new needs, as Andy Smarick explains in “A Conservatism of Creation.” Some of our current institutions haven’t responded adequately to current challenges. If possible, they should be reformed to do so. But conservatives should also create new institutions, when needed. Intelligence does not demand conserving thoughtlessly, for institutions exist for the sake of persons and not for their own continuity.

That same sort of creative fidelity is needed in religion as well. Timothy P. O’Malley considers the tasks facing the Catholic parish in rebuilding neighborhoods and community. Many of his insights are certainly applicable to other religious congregations as well. The development O’Malley describes will require taking belief and practice seriously, a topic stressed by Matthew Hall in his essay on seminary training for Evangelical pastors. Pastors will need real and substantial instruction in doctrine, and they bear an obligation to instruct and catechize their congregations. This is always true, but given current confusions, that responsibility is particularly weighty just now.

Finally, drawing on our archives—and please take the opportunity to read through our past content, which offers insights that are still needed today—Richard Garnett in 2013 used the thought of Mary Ann Glendon to remind us that religious freedom is not merely tied to the rights of individuals but also to the freedoms “that are properly enjoyed by groups, communities, and associations.” That is, to religious institutions. This reminder is all the more necessary given the grave dangers present in the Equality Act. And in an earlier essay of my own, “Social Conservatives Are Right,” I argue that the liberation promised by the mistaken ideas driving the Equality Act is a false vision of freedom, and that both individualism and statism need to be uprooted if institutional freedoms to form free persons are preserved.

As always, thank you for reading Public Discourse. We’re still convinced that society depends on men and women of good will locking themselves together in argument, and still convinced that reason can discover those truths needed for flourishing as persons and nations.