You’ve been reading the names of James and Emily LePage of Alabama in the news lately. Their surname heads LePage v. Center for Reproductive Medicine, the Alabama Supreme Court decision declaring that embryos conceived through in vitro fertilization (IVF) are children, at least, as far as the state’s wrongful death law is concerned. In typical fashion, most commentators have avoided centering on the people at the heart of the matter. The case was filed by the LePages and other families after they were let down by the caregivers they trusted to protect their irreplaceable frozen embryos. In fact, the “cryogenic nursery” at the Center for Reproductive Medicine (CRM) was left so insecure that a patient wandered in, pulled some embryo containers out of refrigeration, and, upon feeling the unbearable cold of the vessels, dropped them. The embryos, and the hopes and dreams their parents had for them, were destroyed.

What many people don’t know is that the inconceivably bad experience of the LePages and other Alabama families is not rare. Fertility is a big business, with billions in venture capital investments pouring into the industry worldwide in recent years. In the United States, that massive growth in profit-seeking hasn’t been accompanied by meaningful regulation or consumer protection. Instead, there has been a burst of incidents, ranging from the unmasking of doctors who impregnated patients with their own sperm, to horrific lab mix-ups, to an explosion in pricey add-on services that don’t actually help patients get pregnant. In just a single week in March 2018, two fertility clinics in Ohio and California devastated more than a thousand families with the news that their frozen embryos—and some frozen eggs—had accidentally been allowed to thaw and perish. “I still sometimes wake up screaming, enraged that I will forever be childless,” patient Monica Coakley recently wrote in STAT.

Regulating IVF in the United States

The last significant regulation of the fertility industry in the United States was in 1992, with the Fertility Clinic Success Rate and Certification Act (FCSRCA). This law requires IVF clinics to submit information about pregnancy rates to the Centers for Disease Control, for ultimate dissemination to the public. The most recent data have shown that success rates in IVF are abysmally low, and even after multiple tries, at least 30 to 40 percent of patients using their own eggs will end treatment still childless. The FCSRCA data were meant to help would-be parents navigate those odds. But the industry itself admits the results are easily manipulated, most commonly by cherry-picking patients; some doctors simply refuse to treat couples who have poor chances of conceiving.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.Since then, instead of meaningful outsider oversight, fertility businesses have been left to police themselves. The American Society for Reproductive Medicine does offer professional guidelines on many hot-button issues, for instance, they urge doctors to resist the temptation to pump up success stats by transferring lots of embryos at once (and to cut down on complicated multiple pregnancies). But the ASRM’s suggestions are entirely voluntary and easy to ignore.

Thus we get awful cases like that of Dr. Donald Cline, who fathered at least ninety-four children with unsuspecting women who thought they were being inseminated with donor sperm or their husband’s sperm. As shown in the Netflix film Our Father, Cline’s offspring were flabbergasted to learn that his behavior was perfectly legal and no federal crime was committed. (He did get hit with a $500 fine and a one-year suspension . . . for lying to investigators). Cline isn’t a lone wolf: dozens of other fertility doctors have now been caught doing the same thing, thanks to revelations from consumer DNA testing companies like 23andMe.

The ASRM gestures toward the fact that embryos have a unique ethical status. Its guidelines say selling embryos is “ethically unacceptable,” while at the same time they give the stamp of institutional approval to payments for donors who turn over their sperm and eggs.

But that warning only gets lip service at California Conceptions, a fertility business with a factory operating model. The company whips up batches of human embryos using the raw materials of sperm and egg donors and then divides them among different women willing to pay to try to get pregnant with them, scattering siblings across the country. California Conceptions children are the result of a bulk ordering process by a corporation looking to find customers for its inventory—and quickly.

Then there’s controversial pre-implantation genetic testing, or PGT-A. In America, it’s routinely up-sold as a chance to reduce the odds of miscarriage, which for fertility patients is like offering a steak to a starving pilgrim. The only problem? This steak is just sizzle. Research shows expensive PGT-A doesn’t help medically normal couples have a baby, possibly because the testing process itself harms their embryos.

Practices like these are devastating for the dignity of everyone involved. The bodies of egg and sperm donors are treated as valuable raw material to be harvested for industrial purposes. Embryos themselves are subject to a degrading quality control process, which calls to mind a USDA livestock inspection. And their parents’ desperation to have children has been turned into a lucrative opportunity for investors who realize pain can be profitable. Can we question the angelic purity of licensed medical professionals and venture capitalists? Troubling news from the world of Silicon Valley fertility start-ups says we probably should. Without meaningful regulation, the human family in our country risks becoming just another tech product.

IVF Regulation Worldwide

It doesn’t have to be this way. In the vast majority of first-world countries, doctors and businesses working on the bleeding edge of bioethics don’t police themselves.

In Germany, for instance, the 1990 Embryo Protection Act limits the number of embryos that can be created in a single cycle to just three. The law centers on issues of consent, raising the possibility of multi-year prison terms for doctors who impregnate women without their knowledge or create embryos without the genetic parents’ authorization. Cloning and elective sex selection via PGT-A are explicitly criminalized.

It’s not just the Germans. From Canada to Australia, from Italy to France, and even in South Korea, non-medical sex selection—or what American clinics euphemistically sell as “family balancing”—is outlawed. South Korea’s regulations in this area come from bitter experience: a strong cultural preference for sons, and the availability of abortion, caused a massive gender imbalance in the newborn population in the 1980s.

Third-party reproduction is heavily constrained worldwide: in Spain, lawmakers allow donors to produce only up to six children, and in Hong Kong, just three. Further protection is coming from the burgeoning movement to abolish donor anonymity, led by donor-conceived adults. In the UK, France, and the Netherlands, children with a background in donor conception are entitled to the name of the person who contributed half their DNA.

Though all of these guardrails limit the profitability of the fertility industry, more importantly, they help safeguard the human dignity of patients and reduce the harms that can arise from reproductive technology—or at the very least they’re a small step in the right direction. Fertility businesses can’t create embryo assembly lines, and instead of being a faceless source of spare parts, sperm and egg donors are identifiable as individuals. Not least, the risk of accidental incest is massively reduced when donor information is available and progeny are limited.

In the United States, there is some forward progress. In 2022, Colorado enacted the “Donor-conceived Persons and Families of Donor-conceived Persons Protection Act,” a landmark bill that forces fertility clinics to identify and maintain contact with donors, and limits matches to twenty-five families. The new law also requires donors to be at least twenty-one years old. These rules protect everyone. Kids have access to up-to-date medical information, instead of a giant question mark hanging over their genetic health histories. Teenagers shouldn’t donate sperm, just as for similar reasons we don’t let them drink hard liquor in a dive bar.

At the federal level, the trend of removing anonymity has received pushback from some in the LGBTQ+ community, who express insecurity around the implication that biology is an important factor in families. But secrets are toxic. And a growing number of donor-conceived adults (and plenty of donor-recipient parents) are raising their voices to affirm that genetic identity does matter, and that recognizing that fact doesn’t somehow invalidate the very real love in donor-affected families.

It’s painful that in the aftermath of LePage, many pundits jumped to repeat corporate talking points. The case paved the way for the LePages and other CRM families to recover damages, even as the industry on the losing side announced a passive-aggressive pause in performing procedures to evaluate their “new” responsibilities under the law. In fact, LePage revealed that patients and fertility businesses have very different conceptions (pun intended) about what’s at stake in treatment. For families, it’s everything. For companies, it’s the bottom line. It’s way past time for consumer protection in the fertility clinic.

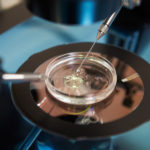

Image by Vladimir and licensed via Adobe Stock.