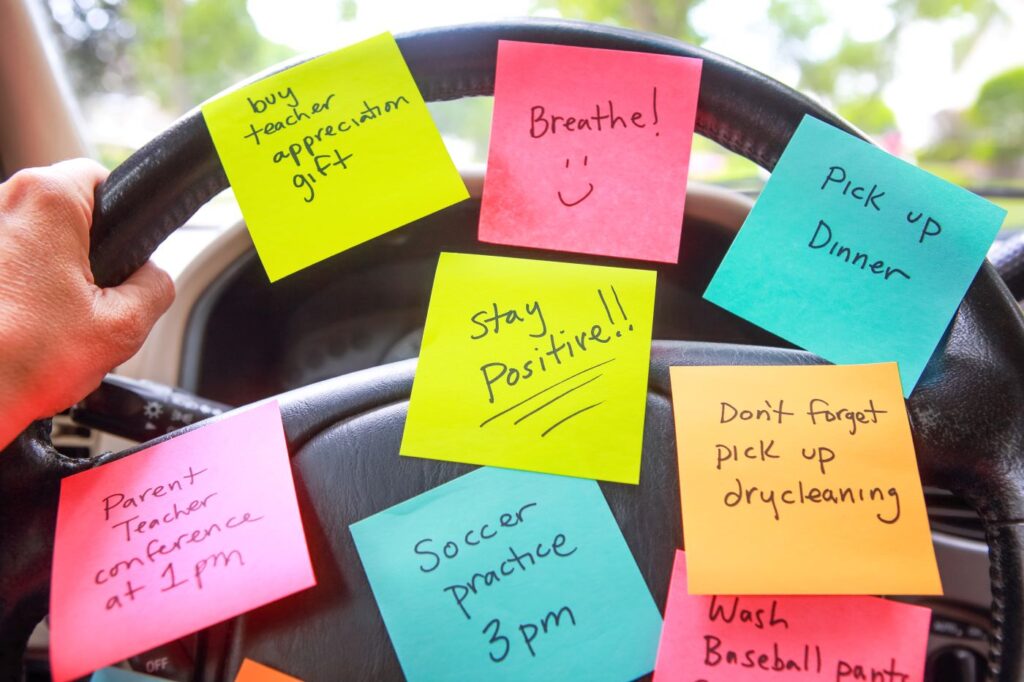

Recently, I was speaking with my husband when I suddenly grabbed a pen and jotted something down on a sticky note. “What are you thinking?” he asked, presuming that it had to do with our deep and meaningful conversation. “I just remembered that I need to add brussels sprout salad to the Thanksgiving menu,” I replied. He laughed. After seven years of marriage, he’s grown wise to the ways of the female mind. “I bet you had three different thoughts in between writing it down and telling me about it,” he said.

Of course, he was right.

A 2019 study published in the American Sociological Review started a cultural conversation about what’s commonly called “the mental load.” The study conducted in-depth interviews with members of thirty-five couples about “the cognitive dimension of household labor,” a form of labor that entails “anticipating needs, identifying options for filling them, making decisions, and monitoring progress.” In practical terms, the mental load includes the planning, preparation, and anticipation that goes into making a household run.

I confess that I wasn’t surprised to learn that “women in this study do more cognitive labor overall and more of the anticipation and monitoring work in particular.” (Interestingly, however, the decision-making aspect of the mental load was much more evenly divided.)

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.Those thirty-five couples were fairly representative, at least of how women on the Internet feel. We’re now having a cultural conversation about women’s “invisible work” and what can be done about it. A New York Times article offers “A Modest Proposal for Equalizing the Mental Load” (“Become incapacitated for six months”); CNN scolds husbands, “No, you can’t just ask your wife to make a list” (“This is how to become equal household partners”); and the popular women’s lifestyle blog, Camille Styles, tells women, “It’s Time We Talk About the Mental Load—and How To Lighten This Invisible Burden In Your Life” (“Buh-bye, burnout”).

But not all the women I know are convinced. Some don’t feel that “the mental load” is a real thing, or at least, one that’s worth fighting about in marriage. Others admit to carrying it but don’t feel that it’s disproportionate, or that it’s the result of men’s being thoughtless jerks.

Last spring, I was having a glass of wine with a friend after her kids had gone to bed. Her husband was on a business trip overseas and I popped over to ease the witching hour of dinner, bath, and bedtime. As we picked up board books and tossed painted wooden cupcakes into the play kitchen, she asked if I had any thoughts on “the mental load.” She and her husband were both working full-time while raising three children under the age of five. She felt burdened by it all, but wanted to handle the situation charitably. She wasn’t entirely convinced by the popular narrative that men just don’t care, yet she found herself managing things in the house and with the children that her husband didn’t seem to notice. “He doesn’t think to cut the grapes length-wise for the school lunches,” she lamented. “But he did cut them when I asked . . . just not the right way. He didn’t realize that it was to prevent them being choking hazards.”

A few months later, I had a different experience. Driving down the interstate in another friend’s SUV, the back seat littered with booster seats, copies of The Boxcar Children, and stray crayons, I mentioned the concept of “the mental load” to a mother of seven, veteran homemaker, and homeschooling mom. “It’s such B. S.!” she exclaimed. “Like my husband doesn’t carry a mental load from the office? Why should I burden him with my stuff? He doesn’t come home and complain endlessly to me. These feminists are so selfish. They’re not the only ones with things on their minds.”

I was struck by the similarities and differences in these women’s responses to the concept of “the mental load.” On one hand, neither was convinced that the best way forward in their marriages was to be angry with their husbands for their different and complementary tasks and burdens. On the other, they differed in their vision of the weight of domestic tasks: my friend who shared in the burden of providing paid income for the family by working outside the home felt the strain more intensely than my friend who has set up the economy of family life in a more “divide and conquer” way: he being the sole breadwinner and she managing the daily housework, childcare, and schooling. She sees the domestic mental load as part of her tasks, just as earning income is part of his tasks.

This disparity made me wonder: do domestic responsibilities weigh more heavily for women who are also carrying an additional mental load from their jobs outside the home? I almost feel the need to whisper this question.

This disparity made me wonder: do domestic responsibilities weigh more heavily for women who are also carrying an additional mental load from their jobs outside the home? I almost feel the need to whisper this question. No sensible person wants to claim that women as a whole are incapable of managing both domestic and paid work. But some women do delight in the choice not to be burdened by both. Their way of dealing with the mental load is to focus exclusively on the domestic sphere, at least for a season.

Other women seem to want to make men think just like women, per the advice offered by CNN: husbands, get your act together and start thinking the way your wife does. It’s not enough to ask her to write down what you could take off her mind—you have to anticipate it yourself. Become a mind-reader. Learn to think like a woman and act as she would. Equality means sameness: if you’re equally bringing in money, you need to equally think about what’s for dinner next Thursday.

But what if there’s a third, more nuanced, approach: one that requires that each couple uniquely navigate these tricky waters of a shared life based on sex differences? I’d like to propose three practices that can help spouses approach conversations and decisions around the mental load and the shared division of domestic labor.

Asking What’s Under the Surface

The first step is to ask ourselves and each other what’s under the surface in our conversations about the mental load. Doing so allows us to identify specific areas for growth and change. For instance, how much of a woman’s desire to plan is tied up in a desire to control or to look good to others? Or, does a woman’s anger at her husband for not carrying a mental load stem from feeling unappreciated, or perhaps resentful of a perceived unfair division of labor? What is a fair division of labor in a marriage, anyway?

Each spouse will bring a certain disposition to this division, and chances are, those dispositions aren’t the same. Usually, some combination of family origin, adolescent fantasy, and personality combine to influence our expectations. The key questions to ask are: What preconceived ideas about domestic labor divisions do we bring to our marriages, and are they serving it well? Is the palpable relief women feel when they talk about the mental load a result of finally finding words to describe something that’s been simmering for a while? Or is a cultural perception of “unfairness” unduly influencing the ways we approach our marriages?

Another helpful question to ask is what’s under the surface in our understanding of how different men and women are allowed to be. Does the mental load feel unfair to women simply because men’s minds don’t work the same way? Is the annoyance ultimately with God or nature? Or do women see men’s natural lack of a mental load around domestic tasks as merely an excuse for laziness? It’s a difficult thing to know, because there are men who are trying hard despite their differences, and men who are skipping out to live selfishly.

The more honest we can be, the better we know ourselves and each other; and the better we can make sense of our feelings and make a plan for positive action.

The more honest we can be, the better we know ourselves and each other; and the better we can make sense of our feelings and make a plan for positive action.

Regular, Open Communication

No two people and no two couples are going to have the same set of likes, dislikes, talents, weaknesses, energy levels, or preferences about domestic tasks. It’s unwise to say that the man should always take out the trash while the woman does the dishes. It’s also unwise to assume that people’s likes, dislikes, talents, weaknesses, energy levels, and preferences about tidiness won’t shift throughout different seasons of life. Any couple who sets a plan for the husband to do the vacuuming while the wife does the dusting and never revisits that plan is primed for disappointment.

Regular open communication in a dynamic life means less risk of resentment building up over dropped information or repressed feelings. Can each acknowledge and validate what’s on the other person’s mind? Sometimes communication is less about the information conveyed and more about the attitude or disposition that’s shared.

These conversations might lead to bigger ones, too: is this all just a bit too much? Is there a way to downsize and cut bills, or get more help, or commit to less? Do we want to live like this? Maybe the solution is less about evenly distributing tasks and more about having fewer tasks in the first place.

Delighting in Difference

Because the differences between men and women have historically been used as the basis of oppression, we’re afraid to acknowledge them. But what if we permitted ourselves to talk about the differences and—if we dare—even delight in them? What if we could see that his failure to cut the grapes correctly was the flip side of his sense of calm when the car broke down? What if we could see that her concern over Thursday’s menu means that no one ends up hospitalized from an allergic reaction? What if the fact that he doesn’t think ahead about Saturday’s soccer game means he also isn’t prone to excessive worry about the future? What if her passion for planning means the family also saves lots of money?

The fact that our spouse has different traits can be frustrating, but presumably, we married him or her because we didn’t want to live with a clone of ourselves. The woman who has the kitchen covered in flour is going to bring cupcakes to the neighbors. The man who’s loud when he walks through the door is also making everyone laugh on a bad day.

Men and women are different; individual men and individual women are different. Marriage involves two very different people building a life together (often with the ongoing addition of more, different, small people), and this building takes work. Any long-term happily married couple will say that the labor is never exactly evenly divided, but a spirit of generosity and good humor will go a long way.

Approaching conversations about the mental load with gratitude rather than resentment is the first step toward a more joyful home. Even if we want our spouse to take more responsibility, we can begin by thanking him for the things we see him do. We can discuss what’s going on beneath the surface when something feels amiss. And we can apologize for, and seek to change, our own selfishness, no matter how it manifests.

Such conversations may lead to rethinking the bigger picture and considering what is necessary to build a flourishing marriage, family, and home life.

And in those moments when comprehension of difference is impossible? Maybe we can learn to just laugh.

Image by soupstock and licensed via Adobe Stock. Image resized.