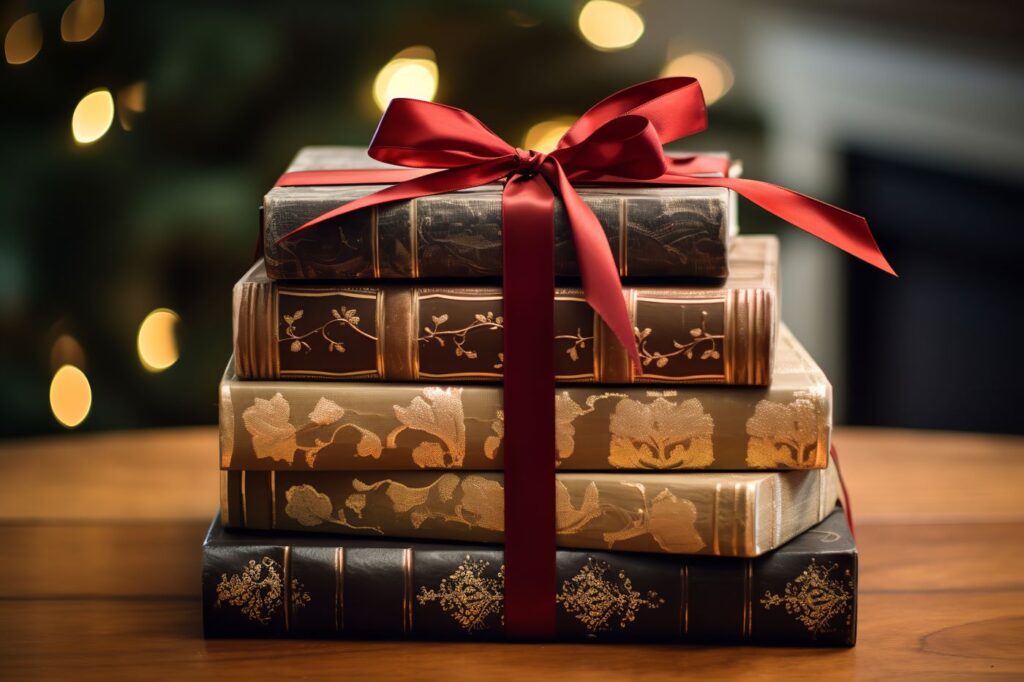

Editors’ note: At the close of every year, we ask the Public Discourse editorial team and Witherspoon Institute staff to write about the best book or books they read that year. We’ve listed the 2023 recommendations below. Happy reading!

Alexandra Davis, Public Discourse Managing Editor

The Lost Daughter by Elena Ferrante

Elena Ferrante is gifted at capturing the mental processes and pathologies that we all equally share, even if ours aren’t nearly as extreme as those her protagonists suffer. It’s fascinating how well-written fiction can feel relevant to us no matter how different our situations may be from the characters’. What struck me most about this short novel (one that I read in two sittings because it was so intriguing) was how Ferrante captured the enchantment and subsequent disenchantment of the protagonist, Leda, with the boisterous Italian family she witnessed on the beach. This disenchantment, intrigue, and fascination are just a few of the many themes she so masterfully introduces in her work.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.John F. Doherty, Witherspoon Institute Director of Finance

Peter the Great: His Life and World, by Robert Massie

In this Pulitzer Prize-winning book, Massie tells of one of the towering figures of European history: the Russian tsar who nearly single-handedly pulled his country’s culture, economy, and armed forces out of the Middle Ages into modernity. Peter’s energy and drive were astounding. Although he was not as well educated as his peers ruling in other countries, he had an insatiable practical curiosity and genius that led him to learn shipbuilding, sailing, and many other skills. Sadly, his boundless determination also made him an unapologetically cruel autocrat: his new capital, St. Petersburg, and navy were built and manned by thousands of serfs; he forced his first wife to enter a convent to dissolve their marriage; and he tried, tortured (by the bloodiest means), and executed hundreds, perhaps thousands, of those who resisted—or were simply suspected of resisting—his iron will, including, most tragically, his son and heir.

Dreadnought, by Robert Massie

Dreadnought focuses not on one person but on the cast of characters of the drama of European international affairs in the decades prior to World War I, especially of the naval rivalry between England and Germany. Massie draws vivid portraits of the great figures of Europe’s golden age, with all their virtues and vices, from Queen Victoria of England to the key cabinet members of the British government: prime ministers like the highly talented Lord Salisbury and the urbane H. H. Asquith, and lesser cabinet members like the young Winston Churchill and John “Jackie” Fisher, who oversaw the production of Britain’s first massive, all-steel ship: the Dreadnought. The dazzling picture Massie paints of nineteenth-century Europe in its twilight all the more brings into relief the tragedy of the Great War that brought it to a crashing end.

Matthew J. Franck, Public Discourse Contributing Editor

The Kristin Lavransdatter trilogy by Sigrid Undset

The best book I read in 2023 is one that many people know and love but was new to me: Sigrid Undset’s Kristin Lavransdatter trilogy. First published 1920–22 in Norwegian, Undset’s novels follow the titular character’s life from girlhood to death in fourteenth-century Norway. It is always difficult for ordinary readers to judge the historicity of novels set long ago in faraway places. But Undset certainly achieves verisimilitude at the very least, convincingly placing us there and then, in a medieval society of landowners, peasants, priests and religious, and warriors—and above all of Kristin herself, a deeply affecting character. The work no doubt contributed the most to winning Undset the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1928. Cluny Media has other works by her in print, and I look forward to reading more.

Readers who desire to read all of Shakespeare’s works in a year can find my annually updated reading plan here. I haven’t decided whether I will reread all the Bard’s works in 2024, but in recent months I have certainly enjoyed watching the forty-year-old BBC Shakespeare series (available on the BritBox streaming service), in which all the canonical plays were produced virtually uncut, starring actors such as Derek Jacobi, John Gielgud, Wendy Hiller, Claire Bloom, Anthony Hopkins, and Nicol Williamson. And I have recently discovered a little classic simply titled Shakespeare, by Mark Van Doren. A renowned teacher at Columbia and a Pulitzer Prize–winning poet, Van Doren wrote Shakespeare in a seven-week burst of energy in the summer of 1938, writing a brief chapter on every play and one on the sonnets and other poems, in brilliant, accessible prose without academic pretensions or theorizing. A highly recommended accompaniment to reading and watching Shakespeare.

Nathaniel Peters, Public Discourse Contributing Editor

Wonder Confronts Certainty: Russian Writers on the Timeless Questions and Why Their Answers Matter by Gary Saul Morson

Gary Morson frames Russian intellectual life as a conflict between those who believe that the world exceeds human comprehension and control and is to be approached with wonder and gratitude, and those for whom ideological certainty permits the mastery of man and nature. This is the kind of book that can only come from a lifetime of scholarship, but that is gripping and accessible to non-specialists. And it’s full of valuable insights into great works of Russian literature that have pertinence in our own time.

Ana Samuel, CanaVox Academic Director

How to Know a Person: The Art of Seeing Others Deeply and Being Deeply Seen by David Brooks

Exposed as we all are to the pressures of high-speed productivity, expressive individualism, and social polarization, there is a collective tendency in America right now for us to run right past—or bulldoze—those around us. Brooks challenges us to cultivate the interior dispositions necessary to enter respectfully and tenderly into other people’s lives and confidences. Combining timeless principles, modern psychological tools, moving stories, and hard-won personal experiences, How to Know a Person is a worthy meditation on life skills and virtues. If it is true that man can only see with his heart, then Brooks sets out to cure us of our blindness.

Serena Sigillito, Public Discourse Contributing Editor

Exogenesis by Peco Gaskovski

Back in October, I happened upon a thought-provoking essay titled “The 3Rs of Unmachining: Guideposts for an Age of Technological Upheaval,” co-written by husband and wife Peco and Ruth Gaskovski. Shortly thereafter, Ruth reached out to me to tell me about the novel Peco published earlier this year, Exogenesis.

The book takes place in a futuristic, dystopian version of our own society—one in which our society’s disordered conceptions of sex, childbearing, and technology have been taken to their logical—if extreme—conclusions. In this world, children are gestated externally, in artificial wombs, and citizens’ behavior is constantly monitored, rewarded, and punished through a complex social rewards system. The story’s protagonist, Maelin, is an officer for the government’s population control unit, which rounds up and sterilizes the children of the Benedites, the dissenting faction of traditionalists who live in the wastelands outside the megacity of Lantua.

This is a novel of ideas, to be sure, but it’s also a fast-paced and compelling read. Although the society Gaskovski describes may initially seem far-fetched, the characters’ justifications for upholding its dehumanizing systems will sound eerily familiar to anyone who has been paying attention to our own.

R. J. Snell, Public Discourse Editor-in-Chief:

On the Marble Cliffs by Ernst Jünger

Jünger’s complicated legacy as an author during World War II and his relationship to tyranny have received a great deal of attention in recent years. The new (2023) translation of On the Marble Cliffs is hailed by some as timely in understanding Trump, although this seems far-fetched to me. What the book captures, however, is the unmaking of order in a society and the role—or lack of role—of intellectuals in the midst of disorder. Jünger gives powerful articulations of a society undoing itself and giving way to violence.

Image by “Davivd” and licensed via Adobe Stock. Image resized.