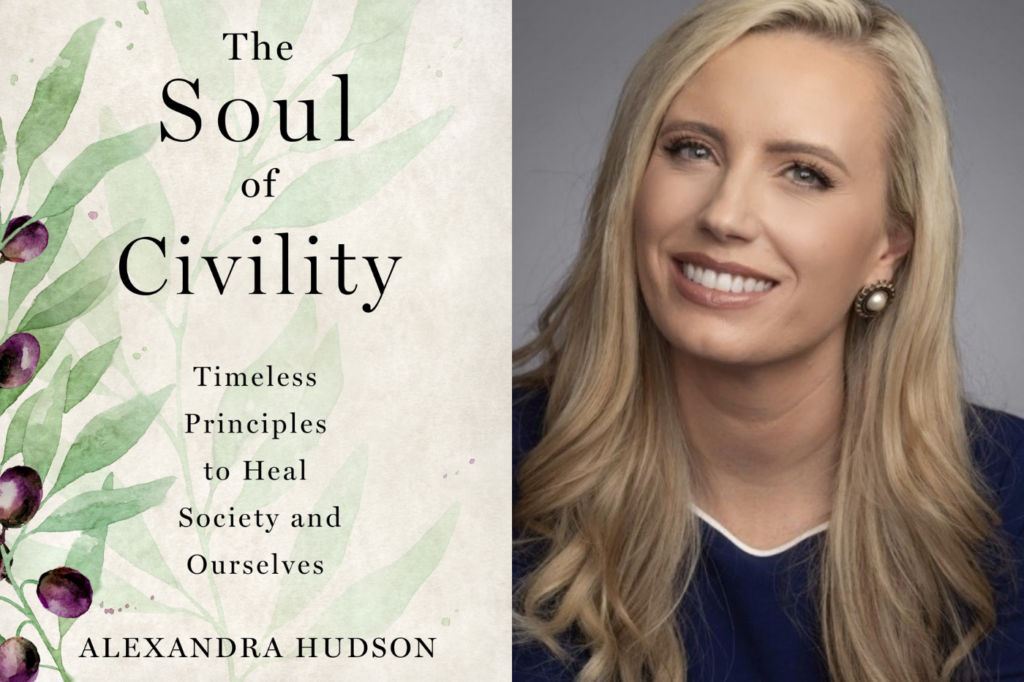

In this month’s interview, Public Discourse’s managing editor, Alexandra Davis, interviews journalist Alexandra Hudson, author of The Soul of Civility. The two discuss the timeless principles of civility, how civility differs from mere politeness, and a case for why we should strive to espouse a spirit of civility within our individual spheres of influence.

Alexandra Davis: Can you tell us what initially sparked your interest in civility, and for those who don’t know, what is the difference between civility and politeness?

Alexandra Hudson: My mother is called “Judy the Manners Lady.” She’s this internationally renowned expert on social norms and what Dale Carnegie, the author of the famous book How to Win Friends and Influence People, called the Fine Art of Getting Along. My mother is passionate about the human social project and the way that manners and social norms facilitate it. So I was raised in an environment that was attuned to social norms and attentive to them.

I’m constitutionally allergic to authority, so I remember always resisting and questioning the norms. And yet, I followed them, and my mom promised me that following them would lead to success in life and school. And she was right, for the most part, until I got to the United States Department of Education.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.While I was working in government in DC in this very divided moment, I saw two extremes. On one hand, there were the people with sharp elbows, the ones who were hostile and willing to step on anyone to get ahead. And on the other hand, there were these people who were incredibly polished and suave and poised, and I thought that these were my people. I realized, though, that these polished people, these were the ones who would smile and flatter me and others and then stab us in the back the moment that we no longer served their purposes.

At first, I thought that these two groups of people were polar opposites. And then I realized, instead, that they represented two sides of the same coin. They both instrumentalize others as opposed to seeing human beings as worthy of respect just by virtue of being human.

With the hostile people, at least I knew where they stood and I knew to avoid them. But the people who operated by the rules of politesse perplexed me. Growing up, my mother said that manners are an outward extension of our inward character. That’s one reason why she was passionate about manners. And here I was, surrounded by these people, and there was this profound disconnect between the outer and the inner. They were polished and refined, but they were cruel and ruthless, especially to people who were less powerful than they were.

That helped me realize this essential distinction between civility and politeness. Politeness is manners, it’s technique, it’s etiquette, it’s behavior, it’s at the superficial, external level alone. But civility is a disposition of the heart. It’s a way of seeing others as our moral equals and treating them with the respect that they’re owed and deserve. In light of that—and this is key—sometimes actually respecting someone requires being impolite. It means telling a hard truth, engaging in robust debate, telling someone that you disagree, that you think that they’re wrong. That’s actually a form of respecting someone, saying, “I see you as my equal and that’s why I’m having this conversation with you. I’m not going to treat you like a child. I’m not going to patronize you and pretend that a disagreement doesn’t exist when it does.”

And so it’s possible to have the polish and the politesse and not be a good person. It’s possible to follow the rules and use them to disarm people and to manipulate them to serve our own selfish ends. Conversely, it’s possible to have the disposition of civility and appear impolite. We hear this rule, “don’t talk about politics or religion at the dinner table.” Those are topics of the highest order. We can’t just not talk about them. We have to. And the disposition of civility enables us to do that because it’s saying, again, “I respect you enough to have a difficult conversation even if we might disagree.”

Civility is a disposition of the heart. It’s a way of seeing others as our moral equals and treating them with the respect that they’re owed and deserve. In light of that—and this is key—sometimes actually respecting someone requires being impolite.

AD: You say in the book that politeness has become a tool of silence and suppression, but civility demands speaking truth to power. Can you unpack that?

AH: To illustrate that point, I tell the story in my book of Edward Coles. Coles is this unsung hero of American history. He was a generation behind the founding fathers, a neighbor of Thomas Jefferson, and an aide to James Madison in the White House when Madison was president. He was a white male, very wealthy. He somehow had this moral conversion. He had just become convinced that slavery was a moral evil that had to be abolished. It was just an unacceptable proposition in America, antithetical to what America stood for. And so at a very young age, he dedicated the remainder of his life to abolition.

When he was in James Madison’s White House, Coles did something really brave. He spoke truth to power in a really important way. He decided to confront America’s primary founding father, the architect of liberty, Thomas Jefferson, with America’s—and Jefferson’s—foundational hypocrisy. Coles wrote Jefferson a letter asking him how he could own slaves while also holding this sentiment that all men are created equal.

So he wrote this letter to Jefferson saying, “Look, I’m part of this abolitionist movement and we could really use your support. Will you please live up to your own ideals and be part of this movement with us?” Thomas Jefferson wrote back saying, “Edward, great to hear from you. Thanks for your note. Thanks for the update. I hear what you’re saying. You’re right. Abolition is going to happen. It’s clear that history is moving in this direction, but you don’t need my help. I’m too old. This is a fight for younger men.” And he just went through this litany of excuses for why he was unwilling to take up the abolitionist cause.

But Coles didn’t leave it there. He wrote back again and said, “I hear what you’re saying. It’s not an excuse. Look at Benjamin Franklin. He was no spring chicken, and he supported this movement.” He didn’t let Jefferson off the hook. Jefferson never wrote back after that.

It’s not polite to call someone out for not living up to their ideals. But it’s really easy to see how, in fact, Edward Coles perhaps respected Jefferson enough to do that, not to coddle Jefferson. He esteemed him, he revered him. He admired everything that he had done and achieved in his life. And he said, “But that’s still not good enough. You’re not living up to those ideals. There’s this misalignment in your value system and your ideas and your practice.” So I love that Coles’s story illustrates the distinction between civility and politeness, why civility demands respecting ideas and people enough to speak truth to power.

AD: At one point in your book, you suggest that certain norms of civility transcend time. Is it true that manners of civility have remained largely unchanged across centuries?

AH: We hear a lot of apocalyptic rhetoric around this problem. People are worried. “We’re on the brink of a civil war, we’re lonely, we’re sad, we’re rude, we’re mean. It’s never been so bad.” There’s just a lot of concern around this topic, this lack of civility in our society. And sure, things are not as good as they could be. Certainly. There’s a reason I wrote this book right now. Again, I experienced this divisiveness viscerally while living and working in our nation’s capital. But incivility is not a new problem. It is not a now problem. It is not an America problem. This is a problem of the human condition.

We are profoundly social as a species. We thrive in relationship with others. In the Hebrew Bible, God created man and woman and said it is not good for man to be alone. And yet we are fallen. We’re profoundly defined by self-love as a species as well—morally, biologically. And those two foundational aspects of who we are, the social and the selfish, are in tension, a tension of competing impulses. And that is why the joint project of living well with others—friendship and community—will always be fragile.

But what was equally fun to discover as I was doing my research in the history of conduct manuals, etiquette books, and self-help books from across history and across culture, was that there is this striking continuity about the timeless principles of human flourishing, the timeless principles of living well together. People have independently recognized that the good life is the social life. The social life takes work, and there are certain rules and guiding principles that facilitate the hard work of life with others, but that make it worthwhile.

That’s how I conceive of civility, remembering those guiding principles that can help us flourish. Again, the problem of incivility will never be permanently solved, but we can do better, certainly, than where we currently are.

We are profoundly social as a species. We thrive in relationship with others. In the Hebrew Bible, God created man and woman and said it is not good for man to be alone. And yet we are fallen. We’re profoundly defined by self-love as a species as well—morally, biologically. And those two foundational aspects of who we are, the social and the selfish, are in tension, a tension of competing impulses. And that is why the joint project of living well with others—friendship and community—will always be fragile.

AD: In one chapter of your book, you write about virtuous cycles and how civility is generative. And you raise the crucial question: to what extent does civility flow from our own hearts and dispositions toward others, and to what extent can it be enforced legally?

AH: I have a chapter that was very fun to write—about why civility supports our freedom and our flourishing. I tell the story of Michael Bloomberg’s politeness campaign when he was mayor of New York City. In the early 2000s, incivility had become so bad in New York that Mayor Bloomberg saw fit to institute a politeness campaign where if you were too rowdy at your child’s baseball game, you could be fined $50. If you were texting in the movie theater, fined $50. If you spit in the street, fined $50. Of course, those are discourteous things, but should they be legislated? Maybe not. New Yorkers did not like being civilized by their local government.

Those laws didn’t last very long. But the point is, across history and culture, the less we put voluntary restraints on our actions, the more autocrats will be tempted to govern our actions for us. The example of the Bloomberg politeness campaign embodies that. If we don’t want to be micromanaged in our everyday interactions, fined for every social infraction, then we should voluntarily choose to keep in mind the well-being of the other, seek the good of the other. That’s what living in community demands. That’s what democracy demands, that we don’t just unilaterally and maniacally pursue our own interests. We consider the interests of others, and that tempers our actions. We have to let our obligations to the other temper what we choose to do and how we use our freedom.

The founders distinguished liberty from license in that liberty was a good use of freedom and license was a bad use of freedom, a vicious use of freedom. Edmund Burke has this great line that manners can ennoble us or they can debase us. He was quite certain of the role of social norms in either elevating or degrading our everyday life.

AD: One aspect of your book that I really enjoyed was its expansiveness. You share the whole history of norms of civility, starting with the epic of Gilgamesh, then working your way through the stoics, then ending with Larry David, of all people. So this is a good time to ask (from a Larry David fan herself!) what does Larry David have to tell us about civility?

AH: I love Larry David, and I love Curb Your Enthusiasm. I think it’s a comedy of manners. It’s one of the greatest shows on television. He is the foremost defender of civilization.

Larry David, in one episode, calls himself a social assassin. When we see someone cutting in line or double parking, we might roll our eyes like, “Oh, look at that jerk.” But Larry David is the one who says, “Hey, what do you think you’re doing? Get back in your car and repark and take up one spot!” He’s going to be the person who goes out of his way to keep everyone else in line. Larry David’s this peer-to-peer accountability mechanism. If we don’t want the government to micromanage us, sometimes all we need is to be kept in check by our peers. If we don’t like the Michael Bloombergs of the world micromanaging our interactions from the state level, we have the Larry Davids of the world to thank for that.

Social sanctioning plays an important role in keeping society intact. But if everyone’s going around and relitigating every minor social infraction, that is too much. That’s always the funny part of the Larry David vignettes: people deny that they’ve done anything wrong in the first place and they call him out for policing them. And then, of course, every episode ends with Larry falling short of the very same thing he calls other people out for.

One of the great heroes in my book, and my life in general, is Erasmus of Rotterdam, this sort of unsung hero of civility and moderation. He was a genius, this intellectual superstar of the European Renaissance, a scholar who spent his life dining with kings and princes. He wrote a book on manners for young children. He, too, thought society was going to hell in a handbasket and that something had to be done to curb the disintegration of civilization. And his book on manners was what he hoped would be part of that. It’s a very, very funny book. It’s categorized by body part. He goes through every body part and says, this is the proper conduct of each part of the body.

But his last line, his last maxim, says, “Readily ignore the faults of others and avoid falling short yourself.” And I think that is the message for Larry David, and the message we all need as well. It’s really easy for us to see the infractions of others and less easy to see our own. It’s easy for us to make excuses for ourselves when we want to cut in line, cut someone off in traffic. We’re too busy to make pleasant talk and see the person on the other end of an interaction—see, and respect them for who they are. We’re always quick to excuse our own shortcomings, but we’re exacting with others. Erasmus flips that logic: ignore the faults of others and hold yourself to a higher standard.

We’re always quick to excuse our own shortcomings, but we’re exacting with others. Erasmus flips that logic: ignore the faults of others and hold yourself to a higher standard.

AD: I can’t let you go without asking you about what you call “porching.” I’d never heard “porch” as a verb until I read your book, and I liked it!

AH: I moved from a very divided Washington to what I hoped and thought were the bucolic rolling pastures of the American Midwest, where my husband’s originally from. One of my first friends when I moved here was a woman named Joanna. She came up to me after church one day and said, “Hi, I’m Joanna Taft. Would you like to ‘porch’ with us sometime?” And I said, “Sure!” We didn’t have many friends there yet. So we went to Joanna’s porch that afternoon, and what I realized was that Joanna was staging this quiet revolution against our atomized and divided society by reclaiming this sort of communal living room, this shared space where she had gathered people across political differences, across geography in town.

There’s this beautiful essay called “From Front Porch to Patio” written by a gentleman named Richard H. Thomas. He talks about how 100 years ago, homes were built with these great big front porches. That marked a social statement that was communitarian in nature. The front porch was a place where people waved to their neighbors. They were places of spontaneous, generative social capital and friendship and community. But then over the course of the last 100 years, the front porch slowly moved to the side of the home and then ultimately to the back of the home, to the modern-day patio. Thomas says that this architectural shift tracks a cultural shift from communitarianism and other-orientedness, presence, and community, to the individualism of our current moment—where the back patio is fenced in, you are not just waving to strangers, you curate who comes in—it’s family, it’s friends, it’s people you want to be there. It’s not just spontaneously being present and seeing whoever happens to be outside your house that day. And then there are things like air conditioning and television that bring us even further into the home, away from others, and isolate us even more.

These are all novel epiphenomena in society that have contributed to this problem and exacerbate, again, an aspect of human personality that we all share: this predisposition to selfishness that isolates us from others. And so that is the cultural metaphor that I use throughout the book. It really represents my theory of social change.

I was frustrated in government. I felt so feckless and incapable of doing anything in this very intractably divisive environment that I was in, and I desperately wanted to be a part of the solution. So I wrote this book. But what I realized is that a lot of people feel that way. A lot of people look at our public leaders and they’re frustrated and they don’t know what they can do. But what I learned from Joanna is that you can do a lot.

If enough of us choose to reclaim the soul of civility and the hospitality that is embodied by porching, we can change the world. We don’t need a front porch like Joanna’s in order to have that disposition of civility and hospitality, that disposition of wanting to transform the stranger into a friend, to make the outsider the insider. Instead of a porch, our tool could be a front yard or a coffee shop. It’s just a way of approaching others in the world. It’s how we live our lives. And Joanna has chosen to live her life by this otherworldly logic. There are lots of people across the country doing that right now, realizing they can’t control what’s happening in Washington or even their local governments, but they’re making their communities and their families stronger, better, healthier, and more beautiful.