Seven months ago in this space I mentioned the decision by Puffin Books, a Penguin Random House imprint of children’s books, to rewrite the stories of Roald Dahl in keeping with contemporary notions of “sensitivity” that are actually of more interest to highly ideological adults than they are to children. I noted at the time that after some pushback, Puffin announced that the original editions of Dahl’s books would continue to be available—as would the bowdlerized new editions. I neglected to mention that one of the organizations that pushed back, to its credit, was PEN America, formed a century ago by poets, essayists, and novelists (hence the acronym) and now open to anyone interested in literature and the freedom that sustains it.

Bravo to PEN America for the stand it took against “fixing” Dahl’s children’s books. But we have now just been through the organization’s annual awareness campaign known as Banned Books Week, which, as Abigail Anthony pointed out at National Review, is not really about “banned books” at all. Poets, essayists, and novelists know a thing or two about hyperbole for effect, of course, and they’re counting on the reactions of half-informed people to the news that more than 3,000 cases of “book banning” occurred over the course of a year in the United States. But like “censorship,” the expression “banned book” suggests something like the litigation long ago over the availability of James Joyce’s Ulysses in the United States. Prior restraint, or subsequent legal punishment for publication, distribution, and sale of a work—these are bans.

On its own website, PEN describes what it means by bans—and they’re not bans at all. They are decisions by adults responsible for the welfare of children about what those children will be assigned to read, and what will be made available to them to read. Those decisions may be ill-advised in some cases. But PEN’s position is that whatever schoolteachers and librarians decide kids should be able to read is by default the standard against which countervailing decisions are understood to be “bans.” Seriously:

It is important to recognize that books available in schools, whether in a school or classroom library or as part of a curriculum, were selected by librarians and educators as part of the educational offerings to students. Book bans occur when those choices are overridden by school boards, administrators, teachers, or even politicians on the basis of a particular book’s content. [boldface on PEN’s website]

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.

School boards, administrators, and politicians—representing parents and taxpayers—employ the “librarians and educators,” of course. If they cannot legitimately override the latter’s choices, who can? Resources are finite—funds to buy books, shelf space for them, the hours, weeks, and years that youngsters spend in school—and decisions about what to buy, shelve, and promote to students are constrained by questions about what can be done to fill a library, and what should be done. Surely school librarians cannot have the last word on such “educational offerings,” as PEN seems to think. Parents too deserve their say, as one vigorous Virginia mother has admirably demonstrated.

Not being a parent myself, I am happily distant from the immediacy of these disputes about what kids will be assigned or permitted to read. But the overwhelming impression I get from the annual agony over Banned Book Weeks is that the publishing industry has a whole subdivision today, known as Young Adult literature, written by fully adult persons who seem to take an unhealthy interest in the sexual development of adolescents, and in morbidly dwelling on the routine emotional difficulties that afflict boys and girls suddenly growing up faster than they had anticipated (a fairly universal experience). In some cases there seems to be a kind of evangelizing going on in such books—the advancement of the sexual revolution’s ideology by means of pandering to pubescent prurience. At the very least there is a trend toward what Carl Trueman, in another context, calls a “therapeutic anthropology” in which “affirming people in their sexual and gender identities seems to be the order of the day.”

In other cases we might be witnessing an author’s ambition to be the next J. D. Salinger, whose protagonist Holden Caulfield in Catcher in the Rye is the most famous messed-up teenager in American literature. Whatever one thinks of Catcher—opinions differ—it has maintained a powerful grip on American popular culture’s image of the teen years as a maelstrom of emotional problems. Salinger evidently wrote the book for adults, but its popularity with high school teachers (much more than with students) bespeaks an effort on their part to “reach” young people with a purportedly realistic depiction of their angst. The “YA” genre of books has in many respects followed suit.

However well intended, such trends seem to me misguided at best and harmful at worst. It is no surprise that there are challenges to the inclusion of such books in local school libraries and curricula. For what young readers need and deserve are models of virtue they can aspire to emulate. I don’t mean spotless characters like the goody-two-shoes Sid, the half brother of the hero of Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. I mean the impish Tom himself, and his still more rascally friend Huckleberry Finn. Yes, Twain’s most famous books, especially Huck’s Adventures with the runaway slave Jim, are full of language that our modern “sensitivity readers” nervously excise. But the power that the “N-word” has to shock us today only increases the impact of Huck’s painful discovery that his conscience is at odds with his racist society. Taken together, these novels of Twain’s are marvelous depictions of growing up. Tom Sawyer gives us a boy’s developing awareness of how a boy should responsibly make his way in the world; Huckleberry Finn gives us a boy’s discovery that being a man will ask much more of him than he had imagined.

The best books for young readers—often with similarly young protagonists, or ones whose stories begin in their youth—can be read or reread with profit by adults. Charles Dickens wrote for all ages, gathering in younger and older readers alike to the life stories of his Oliver Twist, David Copperfield, and Pip, the hero of Great Expectations. Likewise Rudyard Kipling, who could write a book strictly for the youngest kids such as Just So Stories, reached a wider audience with The Jungle Books and still more with Kim, his masterpiece of high adventure whose protagonist is an intrepid and resourceful boy. So too Robert Louis Stevenson, in works such as Treasure Island and Kidnapped, placed youngsters in decidedly adult adventures in which they had to prove themselves.

Young minds are called “impressionable” for a reason. They bear the impress of experience more deeply and permanently than the minds of adults.

The heroes of the books I’ve mentioned so far are boys. What about models for girls? In her recent memoir Necessary Trouble, Harvard’s president emerita Drew Gilpin Faust, an eminent historian, recalls the literary heroines that inspired her as a young girl. First of all came Nancy Drew, a teenage detective who appeared in 36 books from the 1930s to the late 1950s, written by various authors all under the pseudonym “Carolyn Keene.” For Faust, a young girl in the 1950s, Nancy was a true heroine—smart, capable, brave, resourceful, dedicated to justice. “Reading the books today,” Faust writes,

I cannot help but cringe at the racist stereotypes, antisemitic asides, and assumptions of class superiority that exist side by side with the vivid portrait of Nancy. After 1959, the series publisher began to issue revisions of the original stories, removing their most offensive aspects. Sadly, these revised versions also portray a less spirited and independent Nancy.

As the recent brouhaha over Roald Dahl made plain, once the sensitivity readers go after the weeds in a book, much of the wheat is discarded as well.

Aside from “pony books” such as Black Beauty and National Velvet, Faust also gives us vivid memories of the impact two other books had on her: Anne Frank’s The Diary of a Young Girl and Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird. Young Anne was, for Faust, “an embattled champion of the true and the good,” while the fictional Scout in Lee’s novel represented, even more than her father, Atticus Finch, “the beacon of hope and possibility” in the book.

The appeal of young protagonists of both sexes, learning to do the right thing at all costs, probably explains the endurance of Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time books and C. S. Lewis’s Narnia series. These are more than kids’ books, more than “YA” genre fiction to be pawed through by moody adolescents. Like J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, they are companions to whom we can turn and return, seeing more in them each time we meet.

I do have reservations about one well-meaning variety of books for children—the “adaptation” or “retelling” of classics by writers who hope that when they are a little older, their young readers will go on to the real thing, as it were. Sometimes, the more skillfully these are done, the less inclined their readers will be to tackle the original classics on which they are based. When Charles and Mary Lamb wrote Tales from Shakespeare, they did not intend to steer young readers away from Shakespeare, but that might have been the effect. “Oh, I know those stories already!” Similarly, Howard Pyle’s King Arthur and His Knights might have inadvertently prompted young people to give Malory’s Morte d’Arthur a miss.

I speak from a little experience here. For years after reading Edith Hamilton’s classic Mythology as a young boy, I shrugged at the thought of actually reading Homer. I knew how the tale of Troy came out, you see, and the journey home of Odysseus. Silly? Lazy? Yes, both. But young minds are called “impressionable” for a reason. They bear the impress of experience more deeply and permanently than the minds of adults. The parents and other citizens who employ their communities’ teachers and librarians are not wrong to take an active interest in the books they will read.

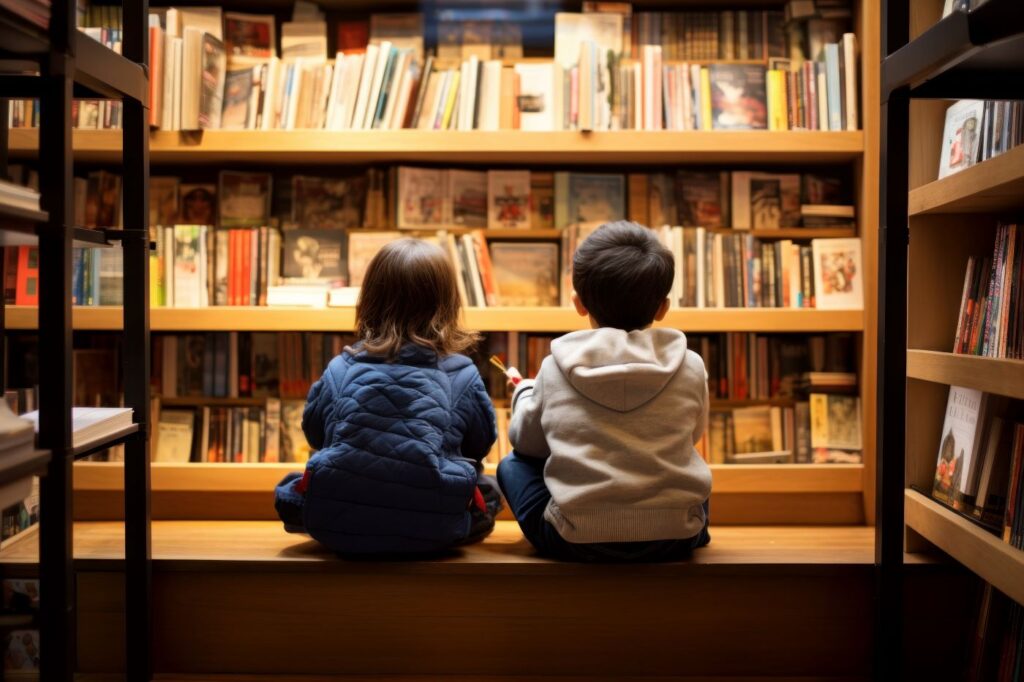

Image by “SnapVault” and licensed via Adobe Stock. Image resized.