With Ukraine’s spring counter-offensive now commencing, the backlash against Russian culture continues in the West, raising the question why one should read Russian literature. Gary Saul Morson, Professor of Slavic Languages and Literatures at Northwestern University, offers a reason in his latest book, Wonder Confronts Certainty: Russian Writers on the Timeless Questions and Why Their Answers Matter. For Morson, to read Russian literature is to live between wonder and certainty—to sit somewhere between an attitude of humble awe and unyielding dogmatism before the world. This oscillation between wonder and certainty not only shaped Russian intellectual, literary, and political debates for the past two centuries but also asks us in the West who we are in our own tradition—whether we are open to wonderment and surprise or smugly satisfied with our knowledge. Simply put, to read Russian literature is to know ourselves.

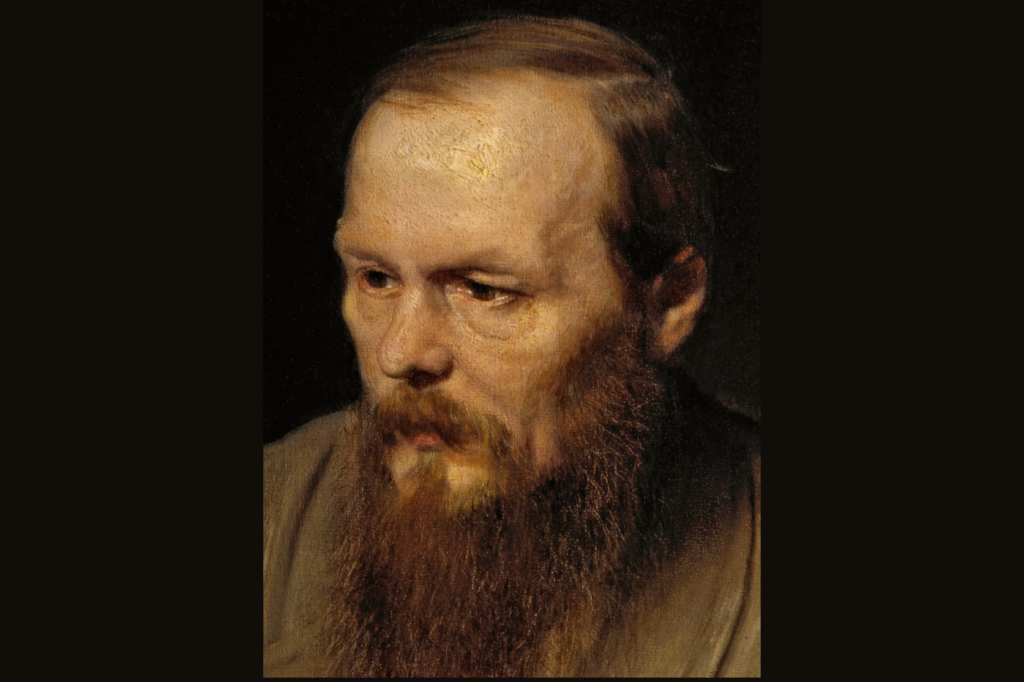

Russian literature is known for wrestling with universal questions about the nature of good and evil, human freedom, moral responsibility, and political utopianism. This is because it was written under extreme conditions. Since the nineteenth century, Russian writers have responded to their country’s experiences that included the liberation of over twenty million serfs, terrorism and political assassinations, revolutions and civil war, famines and Gulags, world wars and the collapse of two empires. As Morson observes, such extremity does “not invite euphemisms.” It created a literary intensity that has perhaps been unmatched since the age of Greek tragedy. The direct confrontation of evil stripped the veneer of civilization, so that Russian writers starkly asked what the human condition was and why suffering occurred. The answers from Chernyshevsky, Dostoevsky, Solzhenitsyn, and others were equally severe and ranged from deep awe before the world to shutting oneself up in solipsistic certainty.

The direct confrontation of evil stripped the veneer of civilization, so that Russian writers starkly asked what the human condition was and why suffering occurred.

The Intelligentsia vs. The Literary Class

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.According to Morson, the best analogue to Russian literature is not French, English, or American literature but the Hebrew Bible, where the “artist communes with God.” Like the Bible, Russian literature came to be perceived “not as a series of separate books but as a single ongoing work composed over many generations.” It is a conversation with both the present and the past simultaneously. For example, Solzhenitsyn’s The Red Wheel is as much a critique of Lenin’s Marxism as of Tolstoy’s philosophy of history in War and Peace. Nothing is untouched in Russian literature, and therefore everything belongs to it. The aim of Russian literature is not just “to amuse and instruct,” but to search for something higher—to discover truth itself.

The emergence of the intelligentsia in nineteenth-century Russia marked the beginning of the “golden age” of Russian literature with Pushkin, Lermontov, Gogol, Turgenev, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, and Chekhov. Morson contrasts these writers with the intelligentsia: university-educated people whose cultural capital in schooling, education, and progressive ideas allowed them to assume moral leadership in Russian politics and public opinion. Belinsky, Dobrolyubov, Pisarev, Chernyshevsky, and others were members of this social class who were certain of their revolutionary ideas and committed to the radical transformation of Russian society.

These two traditions in Russia—the literary and the intelligentsia—had their own canons and their own truths, with the former favoring wonder in art, beauty, and religion, and the latter valuing materialism, utility, and revolution. While Russian thinkers and writers did not always neatly fall into one category or the other, they worked within these two paradigms. Russian society was polarized like our country today, with writers and the intelligentsia corresponding to “red” and “blue” America. This exchange of ideas was aired in public in journals, newspapers, and literature, and lasted over generations.

These two traditions in Russia—the literary and the intelligentsia—had their own canons and their own truths, with the former favoring wonder in art, beauty, and religion, and the latter valuing materialism, utility, and revolution.

Take, for instance, Turgenev’s 1862 novel, Fathers and Children, where the author satirized the protagonist Bazarov, who was a nihilist and member of the intelligentsia. In response, Chernyshevsky published the following year his own novel, What Is to Be Done?, which refuted Turgenev’s claim about the importance and value of beauty and instead remained steadfast in its philosophy of materialist utilitarianism that denied human agency. These ideas, in turn, were mocked by Dostoevsky in Notes from Underground (1864) and Demons (1872), and later rebutted by Tolstoy in his own What Is to Be Done? (1886) which argued for the existence of moral responsibility. Yet in the next century, Lenin published his 1902 pamphlet, What Is to Be Done?, again echoing Chernyshevsky’s novel, and called for a vanguard party to educate and lead the proletariat to revolution.

The Three Archetypes

According to Morson, out of this exchange between writers and the intelligentsia emerged three archetypes that reflected the dominant personalities in Russian civilization. The first was the “wanderer” who was a pilgrim of ideas, often trading one theory for another, in search of the truth. Some writers experienced life-changing spiritual conversions, such as Tolstoy, as told in his Confessions, or Solzhenitsyn, as told in the Gulag Archipelago; while others accepted ideas bereft of God as the source of human salvation, such as Belinsky or Kropotkin. While both writers and intelligentsia looked to ideas for truth, the intelligentsia mistook theory for reality and thus became dedicated to a fanatical idealism. By contrast, writers like Chekhov and Dostoevsky understood the limits of theory in accounting for reality, acknowledging that mystery and wonder were at the root of human existence, and they criticized the intelligentsia for their naïve beliefs.

The second archetype was the idealist—the opposite of the wanderer, because he or she remained steadfast in loyalty to a single ideal, such as Don Quixote in his dedication to Dulcinea. In fact, the character Don Quixote was an object of fascination among Russian writers, especially Turgenev, as told in his essay, “Hamlet and Don Quixote.” In Russian literature there were two types of Don Quixote idealists: the disappointed and the incorrigible. Vsevolod Garshin was representative of the first—disillusioned with reality, accepting the ugliness that it was; Gleb Uspensky was emblematic of the second—unable to reconcile the horrid truths about the peasantry with his idealization of them. Uspensky remained incorrigibly committed to his ideals in spite of reality, leading him to praise despotism and justify policies of cruelty out of an abstract love of humanity.

By contrast, writers like Chekhov and Dostoevsky understood the limits of theory in accounting for reality, acknowledging that mystery and wonder were at the root of human existence, and they criticized the intelligentsia for their naïve beliefs.

The third dominant personality was the revolutionist who loved war and violence for their own sake. Bakunin, Savinkov, Lenin, Stalin, and others represented this Russian archetype. They were motivated by a metaphysical hatred of a reality that could not be explained with certainty, and, with Russian liberal acquiescence, they came to power to murder millions of Russian citizens.

All three of these archetypal personalities reveal the limitations of theoretical thinking in accounting for reality. Russian writers showed how the intelligentsia’s infallible methods of science fell short, as in the cases of Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment, Pierre in War and Peace, and Arkady in Fathers and Children. Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, and Solzhenitsyn explained why human freedom and moral agency existed and why suffering brought one closer to God. Human beings cannot be simply classified as good or evil; doing so, as Solzhenitsyn wrote, was the key moral error of totalitarian regimes like the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany: “The line between good and evil runs not through states, nor between classes, nor between political parties either—but right through every human heart.”

The Mystery of Ordinary Life

Literature, particularly Russian literature, illuminates for us not only the actual but also the possible. There are no ironclad laws of human progress, nor does an inevitable future await us. In his analysis of Russian writers, Morson observes that Solzhenitsyn has shown us the Russia “that might have been” and Dostoevsky has illuminated the “cloud of possibilities” that every human confronts before choosing. As Morson states:

The poetic process suggests that no fate predetermines our future. Possibilities ramify. Constraints limit choice but allow for more than one. There will never be a moment when everything fits and stories are all complete. The future, like the past, will be a series of present moments, and each present moment is oriented towards multiple futures. Time’s potential is never exhausted.

Literature is especially suited to account for life’s endless possibilities, because its attention is on the ordinary—the family, marriage, personal happiness. Chekhov was a master at capturing the ordinary in literature, as were Tolstoy and Grossman. Characters were changed by their choices, but their choices were conditioned by their ordinary context. This is part of Morson’s theory of prosaics, that “Cloaked in their ordinariness, the truths we seek are hidden in plain view.” Meaning is not derived from some intelligentsia’s abstract ideology; it is discovered in our ordinary encounter with the world as it is.

Like Russian writers and their characters, we live in a reality that will always elude our understanding; we can respond with either wonder or certainty. Do we seek a life of contemplation and reflection that always will be incomplete, or one of convicted activism and dogmatic ideology? Does our happiness spring from being with our spouses, children, and local surroundings, or from dreams of an inevitable future of progress and enlightenment? Are we morally free creatures or merely products of a predisposed identity, whether it be race, class, or gender? This is a conversation that all civilizations have, but in Russia it was manifested in literature. All the more reason to revisit its writers and read their works.