Editor’s note: Today’s essay is Editor-in-Chief R. J. Snell’s reply to David Corey’s “A Coalition of the Sensible: What’s Wrong with ‘The New Right.’” This series explores what a principled and sober approach to politics might look like in our current climate of escalating discord. More essays will follow this week.

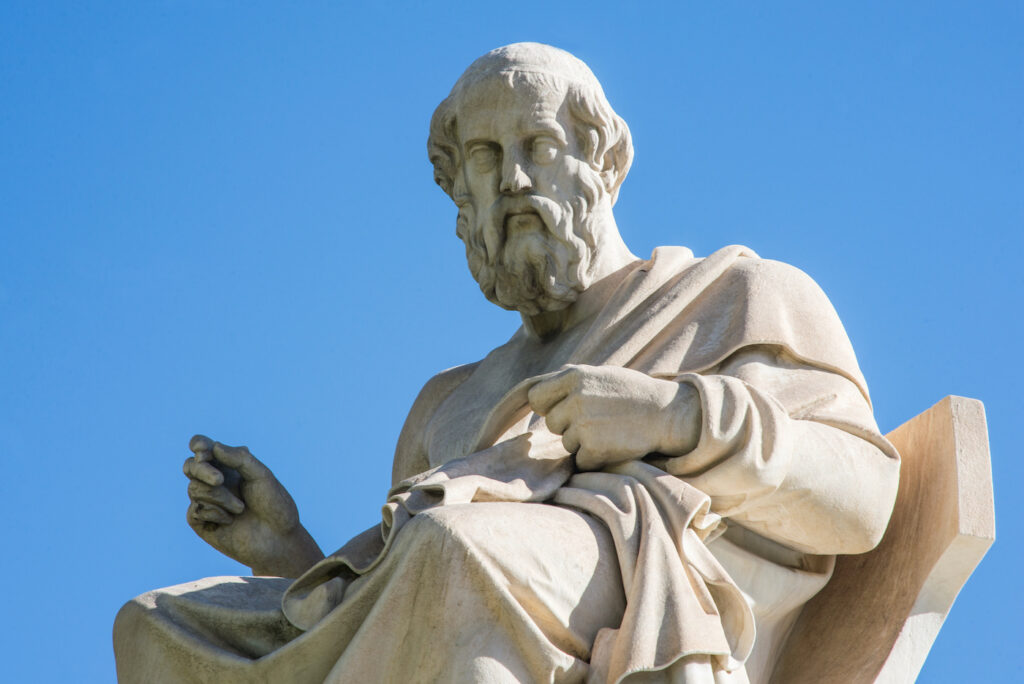

I have taught Plato’s Republic to undergraduates many times. Their response is somewhat predictable, namely, hesitation when the Socratic model of education censors some forms of music, and strong resistance to the structures he suggests to bring about the best city. I don’t blame them, for if the just city requires sharing of spouses, children raised almost entirely by the city, eugenics, and a rigid class system, as Plato appears to suggest, then I, like these students, am not impressed. He simply asks for too much from the political.

However, many students skip over a few brief lines in which Plato imperfectly hints at some profound political wisdom. These lines call into question how literally we are to read his account of the perfect city in the first place. In Book V, Socrates notes, somewhat defensively, that the exercises in “constructing the good city” have been “for the sake of a pattern,” a model in thought, but not at all about “proving that it’s possible” to bring such a city into actual existence. “Don’t compel me,” he states, “to present it as coming into being in every way in deed as we described in speech” since it is “the nature of acting to attain to less truth than speaking.”

As we all know, a theory of politics is not so difficult—likely we all have one, imagining that if only we were able to rule, all would be well, all manner of things should be well. Perhaps we grudgingly admit that since we’re constrained by the current system, not all of our reforms would work, but it would be a pretty good city, far better than the current regime, if our ideas were followed. Let’s call this “rule by late-night dorm room discussion.” Every college sophomore interested in politics has created a utopian system; now if only it could be implemented.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.As we all know, a theory of politics is not so difficult—likely we all have one, imagining that if only we were able to rule, all would be well, all manner of things should be well.

Plato, though, is saying rather more than the obvious fact that it is difficult to implement theories. He does not say “some details of our city in speech will need to be moderated to pass Congress or pass Constitutional scrutiny.” Instead, his claim is more interesting, revealing an understanding of political rationality, albeit an imperfect understanding later corrected by Aristotle: “it is the nature of acting to attain to less truth than speaking.”

On this reading, Plato indicates a scant interest in politics. He never seriously proposed bringing the city of speech into reality, even in a limited or truncated form; instead, the project was always a defense of philosophy as a higher form of life. Action, and perhaps especially political action, is never as true as philosophy. For those who seek truth, thus, the political life recedes in interest while philosophy ascends.

As usual, Aristotle understands the problem better than does his teacher. In the Nicomachean Ethics he notes that the well-schooled person knows the type and limits of precision admitted by each sort of discipline and human endeavor: one does not ask for probability from geometry or certainty from rhetoric. (This, incidentally, is why Aristotle suggests the young are not ready for politics, lacking, as they do, the experience needed to be well-schooled—consider late-night dorm room sessions.) In ethics, as in politics, “the end aimed at is not knowledge but action.”

Distinguishing knowledge from action is not to distinguish truth from action. Plato might think truth is not in action, but Aristotle makes no such mistake. There certainly is truth to be found in action, but it is the truth of action and not the truth of theory. Aristotle knows that reality is variegated, of more than one type, and so too are reason and truth variegated, existing in more than one form. For instance, some aspects of reality not created by us, nor dependent upon us, are yet known by us through various forms of theory. These would include the natural sciences, philosophy, theology, and so on. Another form of knowledge is of thought itself, including the ability to order thought. This is logic. A third form produces and makes, thus techne and poetry. Another type is found in action, the domain of ethics and politics. Science, logic, techne, and ethics are not reducible to each other, nor are the truths of each reducible to each other, and yet none is untrue or less true for that. Instead, they are true in their own, proper, and fitting way. Ethics demands practical reason—prudence—while logic does not.

In a remarkable essay, “What Is Right by Nature?,” Eric Voegelin explains that, not only is the truth of action to be found through prudence—understanding the right time, right way, right means, right extent—but prudence does so in concrete and particular circumstances. Some actions are always morally wrong, Aristotle says, for there is no right way or right time to commit adultery. Right action, on the other hand, is always to know what this person in this moment with these particular circumstances should do. Certainly there are helpful generalities known through tradition and law and custom and proverb, but still, it is you, and only you, who must act here and now in these circumstances. Consequently, Voegelin rightly notes there is “in concrete action a higher degree of truth than [in] general principles of ethics.” The specifics have “more truth, for in action we are dealing with concrete things.”

Again, this does not mean that specifics have more truth than generalities or than theory just as such; not at all. Instead, the specifics contain more truth with respect to action. In metaphysics the generalities have more truth than this or that experience or emotional response about the world, because metaphysics is the articulation of universal principles of being. One would not ask for particular experiences of being from a metaphysician, but for an account of what the principles of all real things are; but in action we are not looking for universal principles of all real things, but for what the correct action is here and now by this person in this situation. (This is not relativism or perspectivism or situationism, by the way, for there really is a truth of the concrete act, and that truth cannot allow for what is immoral or vicious.)

In ethics and politics, thus, there is more truth to be found in the concrete specifics of particular actions than in the city of speech. Plato is entirely wrong about that, even though his mistake does begin the chain of reflection that allows us to understand this political insight.

Not just a political insight but perhaps the political insight: politics has its own proper form of reason, and it is reason concerning what is good and possible to do, given the political specifics of a particular people at a particular time and with their form of government. Not only is this not a theoretical abstraction, it is opposed to theoretical abstractions; not only is this not about late-night dorm room utopias, it is opposed to such as dangerous nonsense.

The coalition of the sensible understands that political action is action and thus about the truth to be had in the concrete specifics.

When we work towards the coalition of the sensible, as David Corey does in his recent essay, we are not calling for moderation as in “split the difference” between the parties. Some months ago I received an email chastising me for using the phrase the “coalition of the moderate,” as if that meant always just finding some mean or median between the left and right, a middle way of compromise satisfying no one and defending no real goods. Not at all. The coalition of the sensible understands that political action is action and thus about the truth to be had in the concrete specifics. Its virtues are prudential rather than the virtues of rationalism, logic, metaphysics, and speculative wisdom (which are just as necessary and just as true, albeit in their own realms).

So it is that Corey’s Four Principles are correct, and a needful rebuke to all dorm room theorists. Actual politics is not “Settlers of Catan” world-making, nor an exercise of fiat and theorizing. In politics we remember (and those who forget are not only dangerous but not sensible) moral limits, limits to coercion, our limited self-knowledge, and the limits of our prudential powers. We can know moral truth, and we can know the truth of a political action—what to do and when—but it is far more difficult to know the truth of action than it is to know the truth of theory. This seems counterintuitive to some, but it is more difficult to be a statesman than to be a physicist. Or, certainly there are far more competent physicists than there have ever been competent statesmen.

The coalition of the sensible is not a coalition of the soft, the weak, the “can’t we all get along?,” or the squishy moderate. This is not a mood calling for peace, peace, when there is no peace; neither is it compromise for its own sake or a winking cynicism about the possibility of moral rights and wrongs. The coalition of the sensible is statecraft, and the realization that statecraft is not found in imaginary utopias, dreams of perfection, or big, brash theories of politics, but in the actual details of human action.

The political warriors of our time are not well-schooled. They have forgotten (if they ever knew) the nature of political and ethical truth, and they go to war with the wrong weapons. They will discover that theory and rationalism and unitary visions of the cosmic common good are entirely unsuited to the task and demands at hand. On the other hand, while “the coalition of the sensible” might not get the blood stirring as a slogan, it is in fact the place and home of the wise.