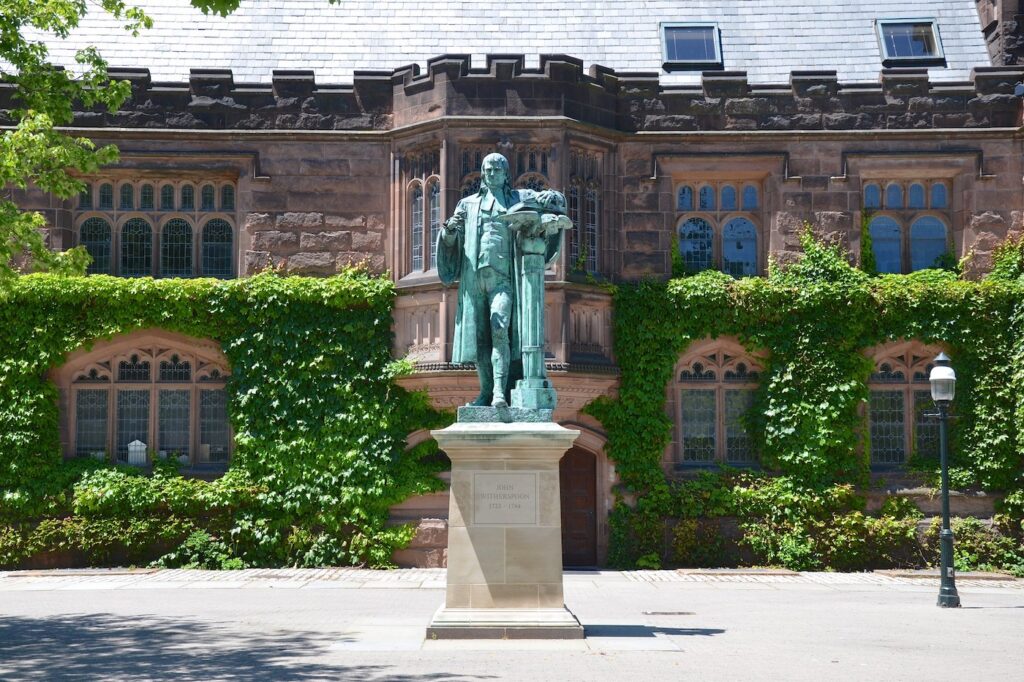

We Americans, like the Romans before us, can be hard on our heroes. Perhaps that is a healthy thing. Plutarch himself wrote that “ingratitude towards their great men is the mark of strong peoples.” Those ancient Romans practiced damnatio memoriae (condemnation of memory) against contemporary public officials who fell out of favor. It was their own version of cancel culture. The especially wicked, like Nero—who lit his garden parties with human torches, and perhaps fiddled while Rome burned—were condemned during their lifetimes, and their statues defaced or decapitated. The Senate occasionally voted a posthumous damnatio against a recently deceased emperor, such as Domitian or Commodus, the latter the murderous and wastrel son of Marcus Aurelius. (Commodus had a statue of his predecessor Nero decapitated and replaced with his own sculpted head; in due time, it was removed after his assassination.) This penalty implied that the name of the condemned had to be erased from public inscriptions, and his image had to be destroyed. So the recent spate of statue toppling, of which the John Witherspoon image at Princeton may become the latest instance, is nothing new. Or is it?

The Romans were not the only politically correct iconoclasts in history. The ancient Egyptians chiseled off the faces of departed pharaohs, and the Greeks smashed tablets with inscriptions to unpopular figures whom they ostracized; after an arsonist burned down the fabulous Temple of Artemis at Athens, no Greek was allowed even to speak his name. The modern world contains examples just as ambitious. The early Soviets, for example, after liquidating counter-revolutionaries, removed their images from photographs, in a twentieth-century version of photoshopping. But all of these condemnations were of contemporaries who had allegedly committed crimes against the state. Leave it to inventive Americans, like the philosophy graduate students at Princeton who have got up a petition to remove the Witherspoon statue, to pass damnatio memoriae on public figures who have been dead for hundreds of years. In this case, the sin that may result in the banishment of his image is that for some years during his time at Princeton he owned two slaves.

Leave it to inventive Americans, like the philosophy graduate students at Princeton who have got up a petition to remove the Witherspoon statue, to pass damnatio memoriae on public figures who have been dead for hundreds of years.

Grandfather of the Constitution

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.The Rev. Dr. John Witherspoon (1723–1794) was sixth president of the College of New Jersey at Princeton, perhaps the most influential clergyman during the Founding, a signer of the Declaration of Independence and Articles of Confederation, and ratifier of the Constitution of 1787. This put him at the nexus of school, church, and state, the three principal institutions that formed what Tocqueville later called “the American character.” Of course it was primarily his indefatigable presidency (1768–1794) at Princeton that earned him, among other honors, a street name in town, a stained glass window in the Chapel, burial in the presidents’ cemetery near Jonathan Edwards and Aaron Burr Sr., and the monumental statue currently under dispute.

The College was barely afloat when he took over in 1768, and his fundraising tours probably saved it from going under altogether. The list of his Princeton graduates is a roll call of notable early American politicians and judges: a dozen members of the Continental Congress; five delegates to the Constitutional Convention; one U.S. president (James Madison); a vice president (Aaron Burr); three Supreme Court justices; a secretary of State; three attorneys general; seventy-seven U.S. representatives and senators; eight U.S. district judges; and two foreign ministers. At the state level he produced twenty-six state judges, seventeen members of their state constitutional conventions, and fourteen delegates to the state conventions that ratified the Constitution.

Every one of these graduates took President Witherspoon’s Lectures on Moral Philosophy, a broad-gauged capstone seminar on political theory that interwove tenets from classical republicanism, Enlightenment liberalism, and Judeo-Christianity. Chief among his graduates was of course Madison, Father of the Constitution and draftsman of the Bill of Rights. The diminutive Virginian stayed on an extra nine months after graduation to study law (and Hebrew) under the “old Doctor’s” direction, and then carried many elements of Witherspoon’s political philosophy into his own public career. Two of the more obvious examples are a system of balances and checks in government (Witherspoon said that branches “must be so balanced, that when every one draws to his own interest or inclination, there may be an over-poise upon the whole”) that Madison wrote into Federalist 51; and the religious liberty and non-establishment Witherspoon endorsed in New Jersey that Madison later incorporated into the First Amendment. Though docents at Montpelier make much of Madison’s study there of confederacies ancient and modern while cramming for the Constitutional Convention, it was his years in the Princeton classroom and reading law privately with Witherspoon that were his formative tutorial in republican political theory.

If Madison is the Father of the Constitution, it is hardly an exaggeration to call Witherspoon its Grandfather. The Pulitzer Prize winner Garry Wills has rightly called Witherspoon “probably the most influential teacher in the entire history of American education.” One might be forgiven for thinking that all of these labors entitle him to the monumental, though realistic, statue whose dimensions are presently complained of. What then, of Witherspoon’s attitude and actions concerning race that threaten to damn his memory?

If Madison is the Father of the Constitution, it is hardly an exaggeration to call Witherspoon its Grandfather.

Witherspoon, Slavery, and Race

In his native Scotland, Witherspoon baptized a captured runaway slave the day before he was sent to trial, christened him “James Montgomery Shedden” (after his son James, and his wife’s maiden name Montgomery), and furnished him with a signed certificate intended to help with his defense. In America, where conditions were markedly different, Witherspoon taught and worked for gradual abolition. In his Lectures on Moral Philosophy, Witherspoon stressed that “it is very doubtful whether any original cause of servitude can be defended, but legal punishment for the commission of crimes,” thus ruling out the African slave trade. However—and today’s detractors make much of this—he did “not think there lies any necessity on those who found men in a state of slavery, to make them free to their own [i.e. the slaves’] ruin.”

Beginning in 1774 Witherspoon admitted two free blacks, John Quamine and Bristol Yamma, to the college, where he privately tutored them; later he instructed Native American students of various tribes, and another free black ministerial candidate. As a member of the Second Continental Congress Witherspoon took a vigorous part in debates, including arguing down the conservative faction that wanted to delay the Declaration of Independence, which of course contained the fateful self-evident truth that “all men are created equal.” (Unfortunately we do not know Witherspoon’s explicit thoughts on Jefferson’s outraged deleted paragraph on slavery in the Declaration, which charged the King with keeping open “a market where MEN should be bought & sold” and is evidence that the draftsman meant for “men” to include all races—as Lincoln, Frederick Douglass, and Martin Luther King were later to interpret it.) Yet by 1780, according to tax records, he owned one slave; by 1784 he had acquired a second.

In the summer of 1787, while Madison and his fellow Princetonians were drafting a new constitution in Philadelphia, their old professor was presiding just blocks away over a convention of Presbyterians who were reforming their denomination’s national constitution, which kept him from serving in the Constitutional Convention himself. That same year he worked on a Presbyterian resolution that approved “the general principles in favor of universal liberty that prevail in America; and the interest which many of the states have taken in promoting the abolition of slavery.” The resolution recommended the education of enslaved persons, and “to all the people under their care to use the most prudent measures . . . to procure, eventually, the final abolition of slavery in America” (original emphasis).

In December of 1787, Witherspoon chaired the New Jersey convention that unanimously ratified the new federal Constitution, that “GLORIOUS LIBERTY DOCUMENT,” as Frederick Douglass described it (all in his capitals), which in Article I put the states on notice that after 1808 Congress could “prohibit” both the international and domestic slave trades. In the event, Congress wasted no time outlawing the “importation” of slaves on January 1, 1808. Though Congress lacked the political will to end the domestic “migration” of slaves, it was of course the stronger union created by the Constitution that made possible the outlawing of slavery across the nation during the Civil War, and in the Reconstruction Amendments that followed it.

After the federal Constitution was ratified, Witherspoon went into the New Jersey state legislature. In 1790 he chaired a committee on abolition, where he proposed a bill providing for gradual emancipation, and expressed his hope that “from the state of society in America, the privileges of the press, and the progress of the idea of universal liberty” (note the mention again of “universal liberty”), slavery would wither away within a generation or two. Witherspoon evidently believed, as Lincoln said the Founders did, that he and his colleagues had put slavery “on the road to ultimate extinction.” Of course no one then could foresee the invention in 1793 of the cotton gin, which would help make slavery far more profitable, especially in the south.

As it turned out, the New Jersey legislature failed to enact Witherspoon’s abolition bill. It would be another fourteen years until it became the last northern state to outlaw domestic slavery. In its 1804 “Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery,” New Jersey mandated the immediate legal emancipation of all children born to enslaved mothers after July 4, 1805 (an acknowledgment of the projective force of the Declaration’s equality clause), though subject to indenture until age twenty-one for females and twenty-five for males.

These terms were markedly similar to those in Witherspoon’s bill from 1790. Though he did not live to see it passed, Witherspoon had prepared the ground for emancipation in New Jersey nearly a decade and a half earlier. In a similar abolitionist vein, Witherspoon had his will revised in 1793. The inventory of his modest estate after his death the next year lists some furniture, china, his library, livestock, and the two slaves valued at a hundred pounds each “until they are 28 years of age”—an indication that they were to be freed if New Jersey did not pass an abolition statute in the meantime. All of this pro-abolition activity put Witherspoon ahead of the curve in New Jersey politics, and his tutoring of Black and Native American students modeled racial integration on the Princeton campus.

Witherspoon evidently believed, as Lincoln said the Founders did, that he and his colleagues had put slavery “on the road to ultimate extinction.”

Statue in Princeton

Now we come to that statue that has stood on Princeton’s storied campus since 2001, catty-corner to the Firestone Library, and, as a librarian once pointed out to me, where Witherspoon has his front to the campus chapel and his backside conspicuously to the theater, which he thought was bad for morals. (The statue has an identical twin near Glasgow in Scotland, home to its sculptor Alexander “Sandy” Stoddart; two others are, at least for the time being, in Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park, and in Washington, D.C.)

Though heroic in height (10 feet tall) and stylized, Witherspoon “in vigorous middle age” is still eminently human. Stout to the point of pudginess, Stoddart’s Witherspoon has a double chin beneath his plain but earnest face. The inanimate features of the statue—the Roman fasces and a book by Cicero; others by Locke, Hume, and Newton’s Principia; an open Bible on the lectern—are symbolic, and admirably represent the elements that Witherspoon compounded into his political philosophy and career. But the man himself, aside from a certain gruff nobility, is not overly stylized; he’s human, which is to say, flawed. A hero in bronze he may be, but with feet (or a midriff, at any rate) of clay, Witherspoon is worth remembering as he is portrayed in Stoddart’s statue.

Having begun with a Roman historian, it might be fitting to end with an Enlightenment philosopher, given the origins of that petition. Immanuel Kant, who was writing his Critique of Practical Reason while Witherspoon was ratifying the Constitution, gave the quintessential definition of “enlightenment”: sapere aude, “dare to know.” One may hope that enlightened Princetonians are made of stern enough stuff to dare to know the whole truth about their heroes; after all, it doesn’t take much daring to forget. Philosophy students, of all people, ought to know that.