Paul Johnson, who passed away on January 12th at the age of 94, was one of the great humanists of the last century. Johnson earned the admiration of millions of readers throughout the world for his way with words, for his insights into historical figures, and for his ability to provide clarity amid the complexities of historical events. Above all, in countless books and essays, he told the story of human dignity in the twentieth century and beyond. It is a story of triumph and danger, victory and tragedy—and Johnson’s commitment to individual freedom made him the perfect storyteller.

I distinctly remember reading Johnson’s 2006 essay “The Human Race: Success or Failure?” in The New Criterion. I was a college senior when I encountered it, and it remains one of the enduring readings of my education. In the essay, Johnson warned readers about “the spread of ideologies based on the proposition that ideas matter more than people” as well as the growth of secularism. Johnson wrote:

Somehow we have to bring back into our private lives, and into our public life, the spiritual element, the sense of awe at the magnificence and possibilities of creation, the pride in goodness and altruism, the fear of wrong-doing and materialistic arrogance, the poetry of the numinous and, above all, the love of our fellow human beings which is inseparable from the belief that all human life, in some way, is created in the image of divinity.

Johnson was not downplaying the importance of ideas—far from it. In fact, he contended “above all” that “love of our fellow human beings” is inseparable from a particular idea, a particular belief in the dignity of people. We might say that the one idea that matters the most is the idea that people matter, because people are made in God’s image. To exalt any other temporal idea above this would be, by definition, inhumane.

Start your day with Public Discourse

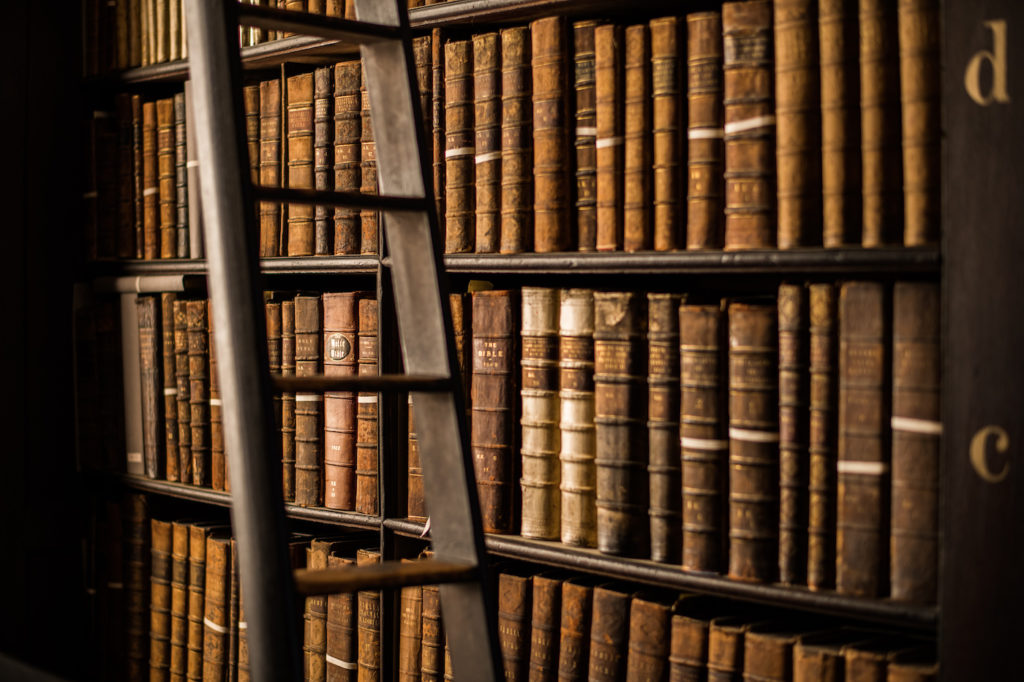

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.Above all, in countless books and essays, Paul Johnson told the story of human dignity in the twentieth century and beyond.

Johnson wrote much about the essential role of religious faith in the world: without faith, he taught, people were vulnerable to other sources of meaning that obscured the proper understanding of God’s image in the human person. The history of ideology since the time of the French Revolution is a sad history of inhumanity, and the documentation of this modern tragedy formed much of Johnson’s work.

Underlying Johnson’s historical writing was the sense that people possess an innate dignity. To Johnson, history was the story of people—flawed, creative, reasoning, exceptional—with the capacity for incredible achievement. People, he thought, were made with a purpose, and that meant history has a purpose.

Consider his stirring tribute to Americans in his History of the American People: “They do not believe that anything in this world is beyond human capacity to soar to and dominate. They will not give up. Full of essential goodwill to each other and to all, confident in their inherent decency and their democratic skills, they will attack again and again the ills in their society, until they are overcome or at least substantially redressed.” It is fitting that President George W. Bush recognized Johnson—an Englishman—with the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2006.

Johnson viewed his mission as a historian as not just to convey facts but also to inspire in people a sense of their dignity. That’s why he wrote so beautifully about people. He was fascinated by human character, by the infinite variety in human personality, and by the way people could shape events.

Johnson’s conception of humanity’s beauty was balanced with a painful knowledge of tyranny’s horror. He understood the bloodiness and the wretchedness of ideologies that elevated ideas over people. Few writers have been able to describe the devastation of the twentieth century as skillfully as he did in Modern Times: The World from the Twenties to the Eighties. And Johnson was unafraid to call out intellectuals for the role they played in the unfolding of tyranny.

Johnson understood the bloodiness and the wretchedness of ideologies that elevated ideas over people.

In the concluding paragraph of his book Intellectuals—published in 1988 on the eve of Soviet communism’s collapse—Johnson wrote, “One of the principal lessons of our tragic century, which has seen so many millions of innocent lives sacrificed in schemes to improve the lot of humanity, is—beware intellectuals.” He warned against intellectuals who sought power or who sought to impose their so-called “expertise” in moments of public decision. “Taken as a group,” he warned,

they are often ultra-conformist within the circles formed by those whose approval they seek and value. That is what makes them, en masse, so dangerous, for it enables them to create climates of opinion and prevailing orthodoxies, which themselves often generate irrational and destructive courses of action. Above all, we must at all times remember what intellectuals habitually forget: that people matter more than concepts and must come first. The worst of all despotisms is the heartless tyranny of ideas.

Johnson was particularly interested in the men and women who sought to defeat the tyranny of ideology and to defend humanity. His short biography of Winston Churchill exemplifies Johnson’s admiration for those kinds of individual heroes. He begins by proclaiming, “Of all the towering figures of the twentieth century, Winston Churchill was the most valuable to humanity, and also the most likable.” For Johnson, Churchill was a hero not just because he defied tyranny, but also because of the way he lived.

Writers dedicated to humane letters like Johnson are rare in our time—and just when we need them most.

One of Johnson’s finest skills as a historian was in bringing his subjects to life. Churchill brimmed with energy and life, and Johnson captures something of the great man’s spirit in his biography. Johnson also wrote about Winston Churchill as a man of the people. He “drew his strength from people, and imparted it to them in full measure. Everyone who values freedom under law, and government, by, for, and from the people, can find comfort and reassurance in his life story.”

Alongside the heroes, Johnson also profiled ideologues who perpetuated “the heartless tyranny of ideas” while claiming to be on the side of the people. He brought to light their false teachings about human nature. Jean-Jacques Rousseau, he wrote in Intellectuals, “believed he had a unique love of humanity and had been endowed with unprecedented gifts and insights to increase its felicity. An astonishing number of people, in his own day and since, have taken him at his own valuation.” Other radical thinkers contributed to the political confusion that culminated in the tragedies of the twentieth century. Karl Marx’s “vision of the dictatorship of the proletariat,” for instance, “was fulfilled in the rise of Josef Stalin,” and the result was Stalin’s “catastrophic assault on the Russian peasantry.”

As for Paul Johnson, there can be little confusion about where he stood when it came to the dignity of the individual. Johnson was a defender of humanity. He made the telling of the human story his life’s work. Writers dedicated to humane letters like Johnson are rare in our time—and just when we need them most. May we carry on the spirit of individual freedom to which he was so faithful.