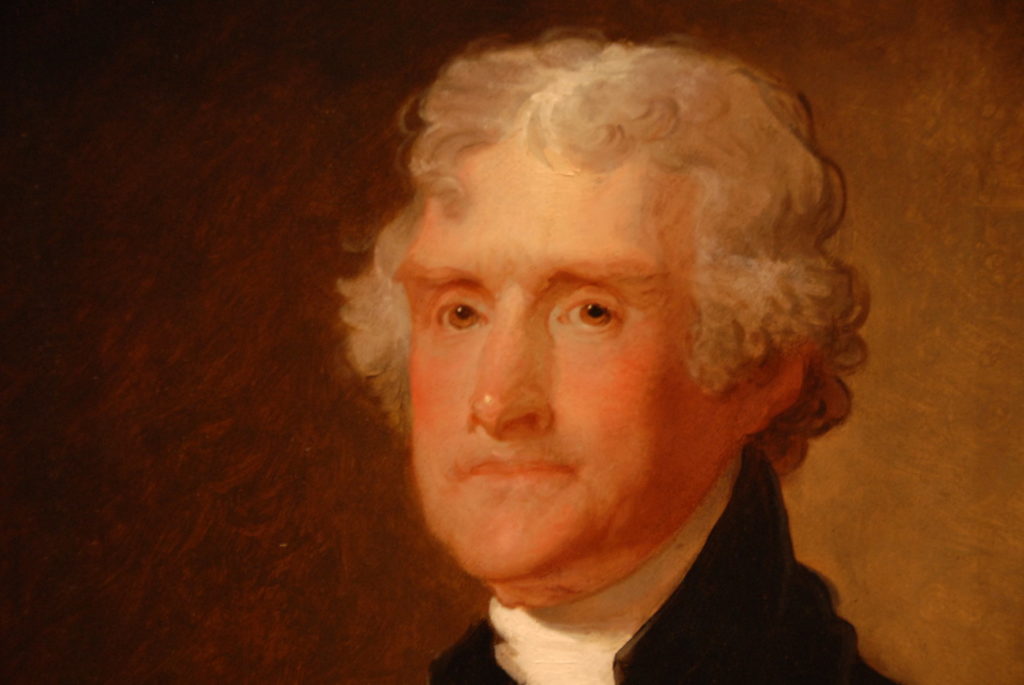

Long before they were dead and buried, the most prominent American founders’ religious beliefs (or lack thereof) had become the subjects of extraordinary curiosity. Their every action, from church attendance to public pronouncements, was assiduously studied for clues about their faith commitments and relations with the Creator. The public’s fascination with the founders’ religious beliefs has persisted, even to the present day. No founder’s religious beliefs have been more scrutinized than those of Thomas Jefferson. In his own day, he was described by one supporter as “a sincere professor of christianity—though not a noisy one”— and by detractors as a deist, infidel, or even atheist.

Notwithstanding the extraordinary attention devoted to Jefferson’s religious and ethical views, they remain frustratingly elusive, especially as they were applied in public life and policies. Thomas Jefferson: A Biography of Spirit and Flesh, by Thomas S. Kidd, one of the most insightful religious historians of our time, is the latest and most illuminating book to engage this topic. Following the arc of Jefferson’s long life chronologically, Kidd assesses Jefferson’s religion and ethics, appropriately placing pertinent words and deeds in the context of his private and public lives. He is also attentive to Jefferson’s views on the prudential place of religion in civic life.

Among the book’s topics and themes are Jefferson’s use of religious proclamations in Virginia to galvanize political support for the patriot cause, invocation of the deity in the Declaration of Independence, design of a seal for the United States, authorship of the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, erection of a metaphorical “wall of separation between church and state” in an 1802 letter to a Baptist association in Connecticut, investigations into whether Christianity was a part of the common law, and composition of the so-called Jefferson bibles. Along with Jefferson’s religion, Kidd weaves into the narrative other topics he found impossible to disentangle from Jefferson’s religious and ethical frameworks, including Jefferson’s lifelong reliance on slavery, intimate and perhaps illicit relationships with the opposite sex, and extravagant spending and accumulation of suffocating debt.

Jefferson and Slavery

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.The biography is unsparing in its attention to the persistent presence and brutal realities of slavery in Jefferson’s world. The Virginian accepted and perpetuated the racism that maintained race-based chattel slavery. He also relished the benefits it brought to his life and lifestyle, recognized its dehumanizing effects on all it touched, knew its corrosive impact on morals and manners, and constantly feared the enmity it engendered. Jefferson and his contemporaries could not escape its incongruity with the American creed so eloquently expressed in the Declaration of Independence’s second sentence, affirming “that all men are created equal.”

While acknowledging that the evidence is not definitive, Kidd accepts the contested claim that Jefferson maintained a sexual relationship and procreated with Sally Hemings, his slave and deceased wife’s half-sister. There is much about this relationship we will never know. Ironically, Jefferson, it seems, thought he was in some sense constrained by the institution of slavery, a predicament captured in his revealing metaphor: “we have the wolf by the ear, and we can neither hold him, nor safely let him go. Justice is in one scale, and self-preservation in the other.” Lacking moral fortitude and political imagination, he did little to redress this injustice and, indeed, perpetuated the travesty.

One cannot escape the contradiction of a slaveholding Virginian proclaiming the great principle that “all men are created equal,” arguably the most important words in any American founding document. We can dismiss Jefferson as a hypocrite for failing to act on the implications of this principle as it pertained to the institution of slavery and to his own slaves. This phrase, however, compelled Americans (and people around the world) to consider its implications for enslaved peoples and the institution of slavery, and it unleashed movements that would ultimately undercut slavery and affirm the dignity of all humanity.

A Real Christian?

If making sense of Jefferson’s conflicted attitudes toward slavery is no easy task, discerning his religious beliefs presents an even greater challenge. Jefferson described himself in private correspondence as “a real Christian,” although he conceded that his religious beliefs were unconventional, even idiosyncratic, once saying he was of a “sect by myself.” In the rationalist tradition, he believed human reason was the arbiter of religious truth. He rejected key tenets of orthodox Christianity, including the Bible’s divine origins, the deity of Christ, original sin, and the miraculous accounts recorded in Scripture. The Christianity he embraced was nonsectarian, nondogmatic, privatized (i.e., solely between him and his god), and rooted in reason.

Despite his deviations from orthodoxy, Jefferson rejected suggestions that his views were of “that anti-Christian system imputed to me by those who know nothing of my opinions.” He acknowledged that his religion was very different from that of the leading churchmen of his day who called him an “infidel and themselves Christians and preachers of the gospel.” Jefferson professed to be a true disciple of the pure doctrines and moral precepts taught by Jesus himself, uncorrupted by Christ’s followers. He believed that Jesus’s moral teachings, stripped of the fiction and artifice carefully crafted by those calling themselves Christians, were “the most perfect and sublime that has ever been taught by man.” Distinguishing the genuine teachings of Jesus from the corrupted or fabricated versions found in the New Testament was, he said, employing an earthy metaphor, like picking out “diamonds in a dunghill.”

Jefferson described himself in private correspondence as “a real Christian,” although he conceded that his religious beliefs were unconventional, even idiosyncratic, once saying he was of a “sect by myself.”

Kidd’s portrait of the man from Monticello, better than previous studies, reveals a man who was a lifelong student of the Bible and who, like so many other founders, frequently invoked biblical themes and language in his political discourse and correspondence. His allusions to both familiar and obscure biblical texts confirm that he knew the Bible from cover to cover.

Why has a clear description of Jefferson’s religion proven so elusive? “I am of a sect by myself,” Jefferson wrote to a prominent Presbyterian clergyman in 1819, acknowledging the idiosyncratic nature of his views. Moreover, he went to great lengths to hide from the public some of his more heterodox opinions, even resorting on occasion to expressing contentious views in code or without attribution.

Unfortunately for Jefferson, written expressions of his controversial religious opinions, intended for a private audience, occasionally fell into the hands of political opponents, causing him much distress. His friend, James Madison, whose religious views could be as opaque and, one suspects, heterodox as Jefferson’s, was much more circumspect than Jefferson in putting his religious thoughts on paper lest detractors get hold of them. One wonders why Jefferson did not learn from Madison to exercise greater discretion. It seems that Jefferson could not help himself, relishing a provocative opinion incautiously shared. Further complicating the search for Jefferson’s religion is that he, like us all, revised and refined his views over the course of his long life. And yet biographers often fail to place his statements in their precise context or notice the season of life in which he expressed them. (Kidd, to his credit, gives scrupulous attention to context.)

Understanding Inconsistencies

Every scholar who has broached the subject, Kidd included, has concluded that Jefferson’s true views on religion and religion’s place in public life are confounded by apparent inconsistencies and contradictions. His words and deeds regarding religion over the course of a long life appear often to point in different directions. To give a few examples, the same Jefferson who steadfastly refused to issue religious proclamations as chief magistrate of the United States also, as the chief executive of his native commonwealth in November 1779, designated a day for “publick and solemn thanksgiving and prayer to Almighty God.” In the late 1770s, as part of the commonwealth’s revised code, he framed “A Bill for Punishing Disturbers of Religious Worship and Sabbath Breakers” and “A Bill for Appointing Days of Public Fasting and Thanksgiving,” the latter imposing punitive provisions on “every minister of the gospel” who failed to hold services on days set aside in the public calendar for religious observance. The same Jefferson remembered as the architect of the “wall of separation between church and state” also endorsed the use of funds from the federal treasury to build churches and support Christian missionaries working among Native Americans. The same Jefferson who denounced the French Protestant theologian John Calvin, even describing his own religion to “be the reverse of Calvin’s,” also organized support for and subscribed financially to a new “Calvinistical Reformed church” in his village of Charlottesville.

A question that looms over this biography is whether there is a key or keys to understanding Jefferson’s thought that will explain the apparent inconsistencies in his record? Or must we accept that Jefferson’s record is one of unresolved inconsistencies? Kidd wisely avoids the temptation to offer glib explanations that claim to reconcile Jefferson’s divergent words and deeds. Nonetheless, there are clues that help one to understand some aspects of Jefferson’s complicated record. For example, notwithstanding cordial relationships with and generous financial support for scores of clergymen, Jefferson sometimes made harsh anticlerical statements. These, perhaps, can best be understood through the lens of pressing political controversies that engulfed Jefferson’s world when he uttered them. He lashed out, for example, at the Congregationalist clergymen in New England who opposed his candidacy in the presidential election of 1800, and the Presbyterian ministers in central Virginia who resisted aspects of his plans for the University of Virginia.

Readers of this richly textured biography are left with a portrait of a brilliant, morally flawed, and often contradictory, overindulgent, and undisciplined man—a combination not uncommon in great men.

There are other possible keys to explaining apparent inconsistencies in Jefferson’s thoughts and deeds. He was willing, for example, to promote a “public religion” despite his preference for a privatized religion when it served secular utilitarian goals, such as educating and “civilizing” those less refined than himself or nurturing civic virtue in the masses. His understanding of federalism, for another example, may explain why as president he was unwilling to issue religious proclamations yet recognized state officials’ authority to issue such proclamations.

Readers of this richly textured biography are left with a portrait of a brilliant, morally flawed, and often contradictory, overindulgent, and undisciplined man—a combination not uncommon in great men. This profile, in some respects, is a metaphor for the nation Jefferson helped shape. This is not a biography for the reader looking for hagiography. It is Jefferson “warts and all,” but it is careful and balanced in its presentation of the evidence, revealing a man of monumental achievements and profound failings. Kidd deftly strips away common misrepresentations and myths that obscure our ability to see the true Jefferson. This biography, exemplifying the best of its genre, will better acquaint both seasoned scholars and general interest readers with the enigmatic Mr. Jefferson.