To considerable fanfare and the surprise of many observers, the matter of legal same-sex marriage has landed on President Zelensky’s desk amid a war that seems unwinnable by either side. An online petition drive has successfully accumulated over 25,000 signatures, the level beyond which the president must consider the matter and render an answer. The generator of the petition appealed to both the uncertainties of wartime and same-sex parenting to motivate her plea, which reads:

At this time, every day can be the last. Let people of the same sex get the opportunity to start a family and have an official document to prove it. They need the same rights as traditional couples.

It’s not the only petition Zelensky must address. There’s the drive to lift the ban on restricting adult men (up through age sixty) from leaving the country—which was rejected—and a move to go online for all education until the end of the war, also dropped. A proposed ban on fireworks and pyrotechnics was understandably supported, then moved to an appropriate branch of government for consideration. There are other petitions on his desk, including removing a statue of Catherine the Great and replacing it with that of a gay porn star, a move that petitioners claimed would send a “clear signal that Ukraine supports the LGBT community.” In light of these more eccentric efforts, one wonders just how seriously such petition drives are taken.

So is the gay marriage petition a stunt? Could President Zelensky push through same-sex marriage by fiat? I don’t see how. Martial law, currently in force in Ukraine, forbids amending the Constitution, in which marriage is described as “based on the free consent of a woman and a man.” Would such a move spit in the face of his cruel Russian counterpart? Certainly. Is Zelensky being pressured to pay for advanced weaponry and an EU membership with cultural favors? Maybe. But would caving to ideological colonization fly in the face of his own people’s popular wisdom? Absolutely.

Start your day with Public Discourse

Sign up and get our daily essays sent straight to your inbox.So is the gay marriage petition a stunt? Could President Zelensky push through same-sex marriage by fiat?

Polling on LGBTQ Issues in Ukraine

There remains a dividing line running south through central Europe—from the Baltic border between Germany and Poland all the way to the Mediterranean border separating France from Italy. Europe is divided—nearly literally—over whether there is a right for two men or two women to marry. That line hasn’t moved much since a pandemic and regional conflict called attention to more pressing matters. Progress toward equal treatment of “unions” has made headway in some countries, but formal marriage less so.

Ukraine, however, falls far to the east of this line. We can quickly learn about the Ukrainian people’s views of homosexuality by examining the latest iteration of the World Values Survey (WVS), a well-regarded international survey project famous for its repeated measures, ample samples, and administration of identical questionnaires across countries. The most recent iteration was administered in Ukraine in 2020—not long ago but before war began with a February 2022 invasion. The Ukrainian data reveal critical judgment of homosexuality and same-sex marriage at rates not seen in the United States in decades.

Respondents were first asked whether they minded the idea of homosexuals as neighbors—the split among those with an opinion was about 50/50. Additional poll data from the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology noted that the share of Ukrainians who have a “negative view” of the LGBT community has decreased from 60 percent to 38 percent since 2016, but what hasn’t increased much is a “positive view.” Instead, indifference surged. Inferring sentiments about same-sex marriage from nebulous opinions about groups and social distance is unwise.

The Ukrainian data reveals critical judgment of homosexuality and same-sex marriage at rates not seen in the United States in decades.

Opinions are sharper about whether homosexuality is “justifiable,” a question posed to respondents together with a series of 18 other “actions” (such as theft, cheating on taxes, and political violence). This item seems to refer to behavior rather than self-identified orientation, and its inclusion in a list of negative items would rouse methodological objections. Nevertheless, respondents didn’t have to be critical. But they were: 42 percent of them said homosexuality was “never justifiable,” compared with less than 2 percent who said it was “always justifiable.” Younger respondents were more sympathetic, but not by much. Just under 12 percent of Ukrainians reported any answer that leaned in the direction of “justifiable.” Hardly a ringing endorsement, but again, what’s pertinent here is that the subject of the petition is not the person—who retains dignity and rights as our neighbor—but the state’s sanctioning and endorsement of same-sex relationships.

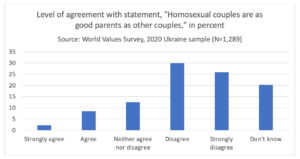

More to the point, however, the WVS asked about the topic of same-sex parenting, a topic mentioned in the petition. The WVS asked respondents for their level of agreement about the statement, “Homosexual couples are as good parents as other couples.” Here, too, there are elevated rates of respondents who did not want to offer an opinion: 20 percent said they didn’t know. Others had an obvious opinion: 26 percent disagreed strongly, 30 percent simply disagreed, and 12.5 percent neither agreed nor disagreed. Only 8.5 percent agreed, and just over 2 percent strongly agreed that homosexual couples were just as good as other couples.

Relationship Types and Children

Of course opinions about same-sex parenting can be out of step with the research. But ten years after I began a fire walk over the topic, I’m still convinced that there are differences between mothers and fathers, and that relationship types have significant impact on children. Why? Because the purported “consensus” that children from same-sex households fare no differently than children from opposite-sex households—in particular, married families—is the only real social construction here. The story of “no differences” between same-sex and opposite-sex households with children hinges on a pair of repetitive themes in the published research: (1) hiding behind small and nonrepresentative samples, and (2) employing analytic strategies that all but guarantee motivated researchers can “explain away” those pesky baseline observable differences between children from same-sex and opposite-sex households.

Baseline differences matter. What happens before control variables matters. Building statistical models to hide differences is called p-hacking, a common but problematic practice. A 2020 study of over 1.2 million children in the (gay-friendly) Netherlands, whose primary media message trumpeted how same-sex parents were better than opposite-sex parents, nevertheless revealed that 55 percent of children living with same-sex parents—the vast majority of which were female couples—experienced the separation of these parents, well above the 19 percent of children of opposite-sex parents who experienced the same. “Controlling” for such instability—in effect implying it doesn’t matter—clears the way to proclaim the benefits of same-sex parents. It’s a common statistical practice, but a deceptive one.

Hence, alternative analyses are always a good idea. For example, a 2020 published reexamination of three nationally representative datasets from the United States and Canada revealed that the presence of children tended to stabilize opposite-sex couples but destabilize same-sex couples. Dissolution rates were 43 percent for same-sex couples, but only 8 percent for opposite-sex couples. Its authors agree, saying that “parental instability is an important factor through which parents’ sexual orientation influences children’s outcomes.” In light of both Ukraine’s cultural stance on LGBTQ issues and the data on same-sex union instability, a presidential fiat legalizing same-sex marriage would be an affront to the nation.

If same-sex marriage becomes a reality in Ukraine, it will leapfrog much of central Europe—Italy, the Czech Republic, Poland, Hungary—and all of its eastern European neighbors, where no such arrangement exists. It would be the product of a president eager to please aggressive Western cultural imperialists now bent on softening up the defense of marriage by associating its supporters with Vladimir Putin, who would no doubt parlay any endorsement of same-sex marriage into motivation for further aggression in the Donbas.

If same-sex marriage becomes a reality in Ukraine, it will leapfrog much of central Europe—Italy, the Czech Republic, Poland, Hungary—and all of its eastern European neighbors, where no such arrangement exists.

While same-sex marriage may seem to be the holy grail of LGBTQ rights, it is no longer the end game for many in the movement. Instead, “marriage equality” often serves as a beachhead from which efforts to further subvert the dimorphic understanding of male and female can be launched. Not only is marriage considered a social construction by many progressives, but so are the very “men” and “women” who compose marriages. Younger sexual minorities are more apt to consider longstanding marital norms “boring, sexist, monogamous, and confining . . .”

Securing a free Ukraine remains a meritorious venture. Holding Russian leadership accountable for the military’s targeting of civilians and other atrocities is a just cause. But any capitalizing on Ukraine’s current dependence on the US and EU governments by encouraging its ideological colonization in the utter absence of popular support would be not virtuous but vicious. If the war in Ukraine is indeed a culture war, one about “democracy, and Ukrainian culture, past and present,” President Zelensky would do well to preserve what his own people wish to maintain—the structure and meaning of marriage, which is the very heart of social reproduction and the continuity of nations.